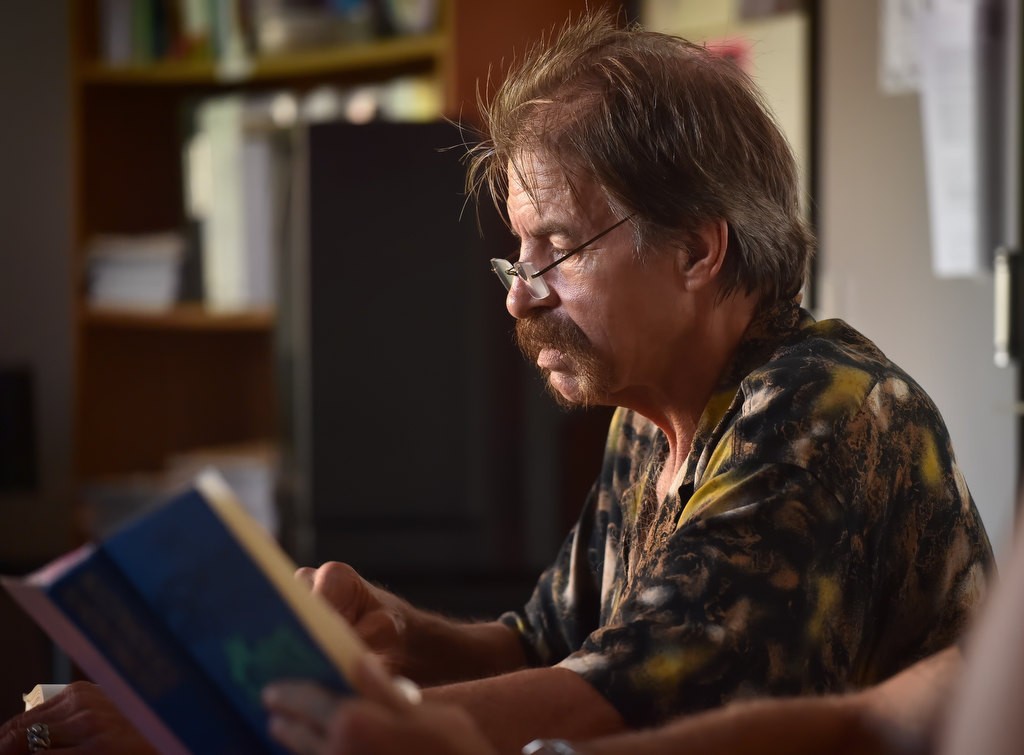

Peering through glasses, the college student flipped to a page to silently read along as a classmate read a section aloud.

Bill Easton listened intently, the picture of a serious student soaking up knowledge.

Prior to a couple of years ago, the only thing Easton was interested in soaking up was toxins — a never-ending stream of drugs to satisfy his only real desire:

To get — and remain — high.

For about 45 years, dating back to his teens, Easton had been awash in mind-altering substances.

Booze, beginning when he was 15.

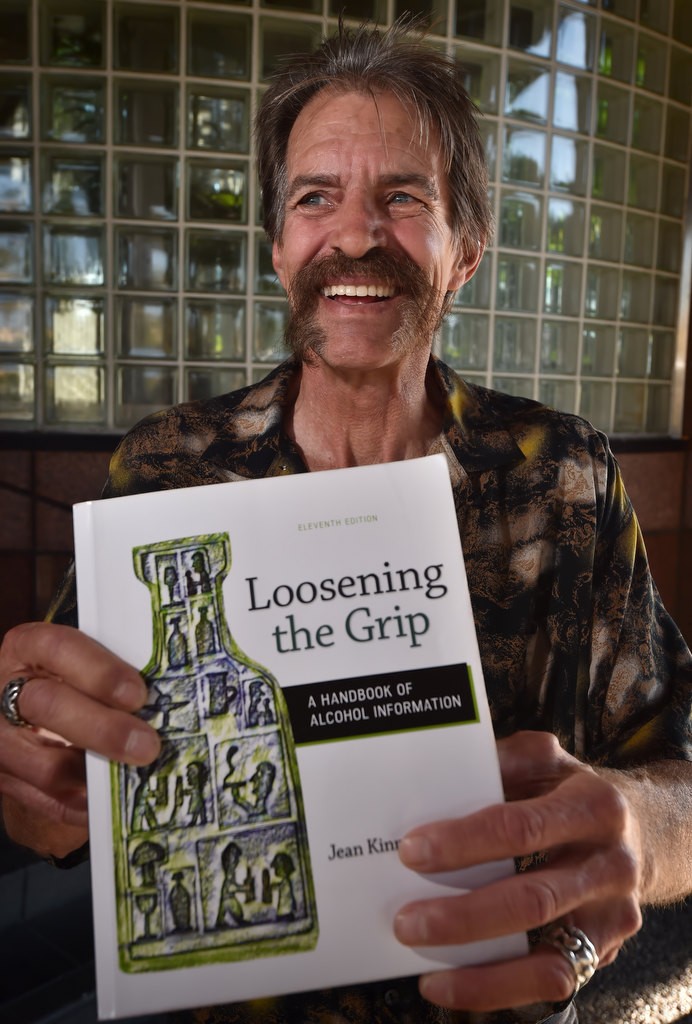

Recovering addict Bill Easton with one of his course books at InterCoast College.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“Scientific experiments” with hallucinogens in the ’70s.

Speed in the ’80s.

Mushrooms.

Ecstasy.

But mainly, over the years, methamphetamine — the extremely addictive stimulant Fullerton PD officers caught him in possession of during a raid on his home on Sept. 27, 2013.

That arrest let to three felony charges.

It took Easton a while to get clean, but he’s been sober since May 13, 2014.

And because he successfully completed treatment for alcohol and drug addiction, he was sentenced to 365 days in jail, but the sentence was waived. He also was put on three years of formal probation, but that recently was knocked down to informal probation because a judge was so impressed with his progress.

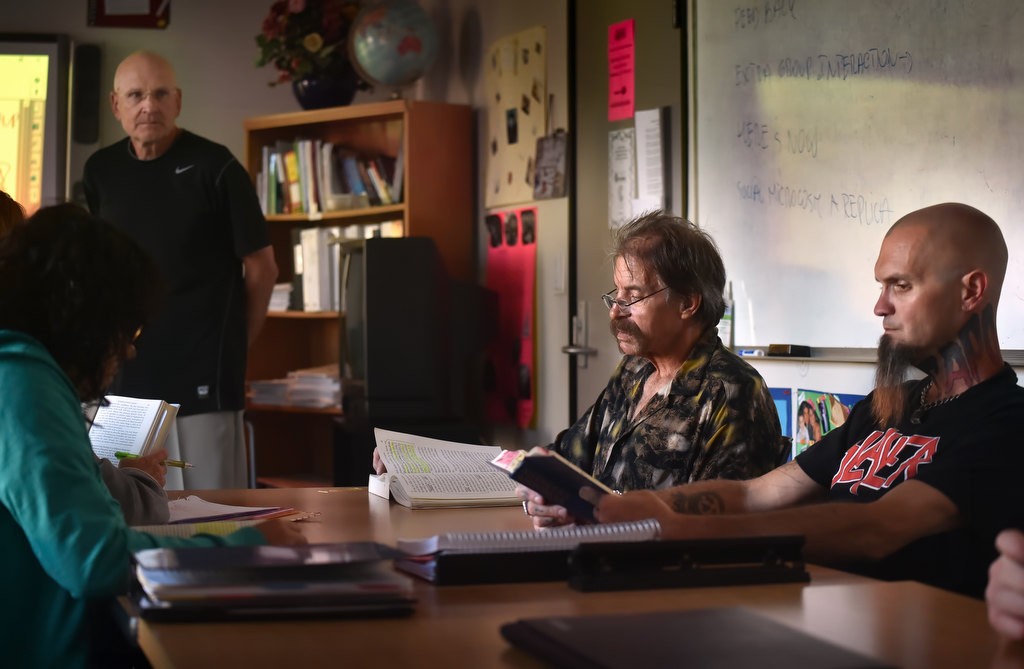

Bill Easton, second from right, is studying to become a counselor to help drug and alcohol addicts.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Easton, 63, credits his arrest by FPD Corp. Kenny Edgar for getting the difficult journey to sobriety started, along with well-known defense attorney Lloyd Freeberg, whose sobrietylaw.com practice specializes in helping clients who are facing criminal charges stemming from drugs and alcohol.

Behind the Badge OC first wrote about Easton’s journey last September (click here) — a story, Easton said, that brought many old acquaintances and relatives who had lost track of him out of the woodwork.

Recently, we caught up with Easton to see how he’s doing.

Great, it turns out.

Sipping coffee on the patio of a Starbucks on a breezy late afternoon, clear eyed and wearing jeans and a dress shirt, Easton was on his way to evening class at InterCoast College in Orange.

He’s in the midst of a 10-month course to become a certified substance abuse counselor — a course he’s set to complete in October.

The visit happened to be day No. 765 of Easton’s sobriety — progress he tracks on the app Sobriety Counter.

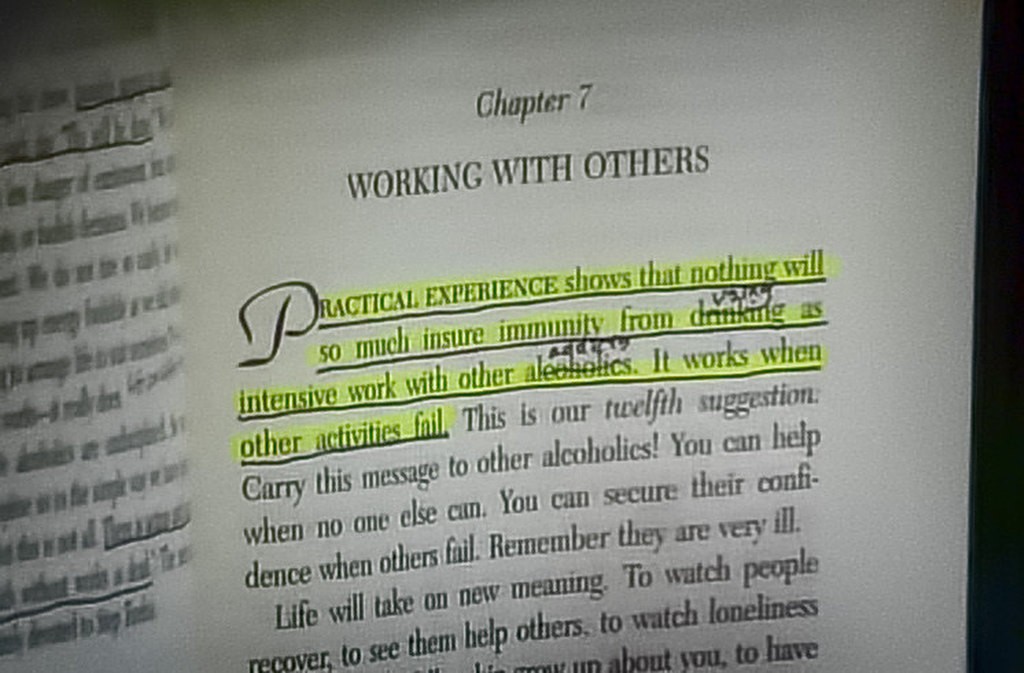

Underlines, yellow highlights and word replacements mark the book, “Alcoholics Anonymous,” being read during a class at InterCoast College.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Easton knows it’s one day at a time.

He is, as he says, “learning to live all over again.”

He gets emotional when he thinks about all the wasted years during which, against odds, he more or less managed to work regularly as a carpenter — but messed up a number of relationships while putting his body and mind through the wringer.

Easton’s near-constant state of inebriation for 45 years almost cost him the relationship he cherishes most in the world: his daughter, Jessie, now 28, who for a while moved out of state because she didn’t want to watch her father slowly kill himself.

That move was one of the factors that led Easton to his dramatic turnaround — a former meth head down to 11 teeth who now has a new set of gleaming-white choppers.

And now Easton is living with Jessie, her husband and her in-laws in Garden Grove.

She works as a bartender at Angel Stadium.

Easton laughs at the irony.

***

Easton attends InterCoast College four days a week. The evening classes last four hours.

He scored high on the entrance test and got a grant that covers $13,000 of his $19,000 tuition. The rest is covered by a student loan.

“I want to try and give back,” Easton said when asked why he wants to counsel drug and alcohol addicts. “I know what it’s like to be there.”

He isn’t working yet because he wants to concentrate on school. He gets by on $1,000 a month from Social Security.

Easton is a star student in the class of about a dozen.

With textbooks including “Loosening the Grip,” “Working With Others” and “Enough Already! A Guide to Recovery, From Alcohol to Drug Addiction,” he’s sailing by with a solid A.

A recent homework essay, “Qualities of a Good Leader,” earned Easton an A+.

But he insists he’s no genius.

“People think I’m smart, but they’re smarter than me,” he says. “I just hope (other addicts) address their (addiction) issues much sooner than I did.”

Easton regularly attends an AA meeting in Fullerton.

He recalled one member who told him the goal was to be sober more than the number of years spent whacked out on drugs.

Easton did the math.

To reach that goal, he will have to live to 106.

Don’t count him out.

An aunt lived to 104.

As Easton headed out to class, he pinched himself.

“Never in my wildest dreams,” he said, “did I think I’d be here.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge