Jeff Swaim is just a few weeks into retirement, after serving for nearly 29 years as a La Habra PD officer, and he’s enjoying — and looking — the part.

The former captain, who cut his teeth at the agency as a volunteer, when he was barely a teenager, is sporting a goatee.

For a recent interview, the Harley-riding ex-officer showed up at the station wearing jeans and a T-shirt from a Laughlin River Run motorcycle rally that pays tribute to military personnel who have died defending the freedom of Americans.

“They’re lucky I didn’t show up in shorts,” Swaim, 50, joked about his LHPD family.

Although walking away from a lifelong career has been bittersweet, Swaim, who got a formal sendoff Tuesday, Jan. 17, by the La Habra City Council, has no doubt it’s time.

He always planned to retire at 50.

“It’s hard to leave the clowns,” said Swaim, referring to his former colleagues, “but not the circus.”

And a circus it’s been.

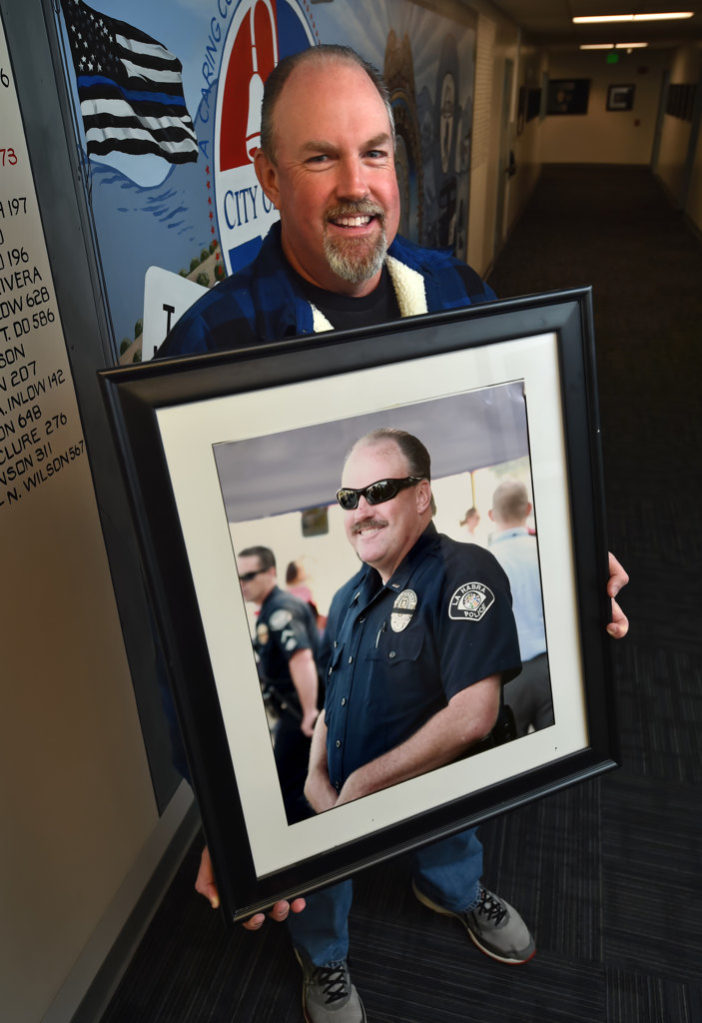

Retired Capt. Jeff Swaim talks about life after police work.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Swaim, the first in a wave of LHPD veterans expected to retire in 2017 (technically, he retired on Dec. 23, 2016), pretty much has done it all at the agency, from undercover narc to school resource officer (SRO) to jail manager to supervisor of the K9 unit.

Throughout his career, Swaim has embraced — and appreciated — the family vibe of the agency, which in the ’90s faced serious gang-related crime, but these days enjoys a greatly reduced gang problem and a close bond with residents and businesses.

“The community likes the department, and the department likes the community,” Swaim said. “We do a lot to go above and beyond to serve, and we get a lot of support.”

YOUNG VOLUNTEER

Swaim grew up in La Habra, the only child of parents who both were teachers.

When he was 13, Swaim’s father, Hal, a CB radio user, joined other La Habra CB users to help the LHPD out in a kind of neighborhood watch role.

Swaim joined his father for the fun, and soon was part of La Habra’s REACT/Radio Patrol, a group of CB enthusiasts who would alert LHPD dispatchers of any suspicious activity they came across in the city.

“That kind of got me involved in wanting to pursue a career in law enforcement,” said Swaim, who went on to become a police explorer for the LHPD and later, a cadet.

He worked part time as a dispatcher, while putting himself through Fullerton College’s Police Reserve Academy, and shortly thereafter, Golden West Police Academy. He was sworn in as a La Habra PD reserve officer in November of 1987.

“I was working the front counter as a cadet one day when I was told the chief (at the time, Ron Meehan) wanted to see me,” Swaim recalled. “I figured he would throw his car keys at me and tell me to get his car washed and gassed.”

Instead, Swaim was in for a surprise.

“So, Jeff,” Chief Meehan said. “You want to work here as a reserve police officer?”

“Yes sir, I do.”

“OK, go ahead and raise your right hand.”

Chief Meehan swore him in on the spot, and Swaim excitedly called his parents.

In March of 1988, Swaim was sworn in as a full-time LHPD officer at age 21.

ONE OF FIRST SROs

Swaim started in patrol and then, a few years into his career, he was selected to serve as one of the department’s first school resource officers at his alma mater, Sonora High.

His first day as an SRO was memorable.

“There was a report about a student with a loaded gun on campus,” Swaim recalled. “I pulled him out of a classroom and arrested him. He was showing off his weapon.”

Swaim then transferred to the Special Investigations Unit and grew a ponytail to work narcotics for a few years.

“A doper told me I looked like Steven Seagal,” Swaim said with a laugh.

Swaim loved working narcotics.

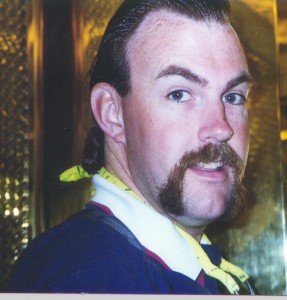

Swaim as an undercover narcotics detective. A doper at the time told him he looked like the action star Steven Seagal. Photo courtesy of LHPD

“Just because of the characters I met,” Swaim explained. “They’re funny people to deal with because they do such weird things.”

Swaim was promoted to corporal and went back to patrol, and then rotated into the gang unit for two years.

“That was my most frustrating assignment,” Swaim said, explaining that the suspects didn’t seem motivated to get out of the gang life.

“You couldn’t get an answer from some of them as to why they did what they did — why they would hang out on street corners waiting to be shot. The answer they gave me was, ‘For my neighborhood.’ Again I would ask them, ‘Why?’ There was so much more they could do with their lives and better things they could do for their neighborhood.”

One of Swaim’s most notorious cases happened in March of 1998, while he was working as an investigator. Several concrete cylinders, some seeping blood, were found scattered around a neighborhood.

In this file photo from August 2016, La Habra Capt. Jeff Swaim, left, listens to religious leaders during a community gathering as they talk about how much the men and women of the police department are appreciated. File photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

The cylinders contained the remains of a12-year-old child, La Habra resident Juan Delgado.

John Samuel Ghobrial, an Egyptian national and panhandler, eventually was arrested and sentenced to death for molesting and dismembering the boy’s body.

“I hope to be able to go to his (execution) one day,” Swaim said.

Swaim promoted to Lieutenant in 2002 and, after several years in patrol, was selected to oversee the General Investigations Bureau. He promoted to captain in 2014.

While not one to mention his accomplishments, Swaim’s dedication to service during his tenure with the department earned him many accolades including a Chief’s Citation, Career Service Medal, and being named co-recipient of the American Legion’s “Officer of the Year.”

ADJUSTING

These days, Swaim enjoys riding his Harley, camping and boating with his wife, and spending time with his 88-year-old father.

He reflects on law enforcement, where it was when he started and where it is headed now, and hopes the current anti-cop climate soon dissipates.

“There are too many cops dying out there,” Swaim says. “The executions that are happening are the worst. We are lucky in La Habra to have great support from the community, but what happens nationally impacts all of law enforcement.”

Swaim recalled patrolling La Habra in the wake of the Rodney King beating and being stopped at a red light.

A young boy, maybe 5 years old, was crossing the street with his father when the boy turned to Swaim and flipped him off.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Swaim said.

Swaim said he will maintain close ties to La Habra, but said it feels a little weird being retired.

“I’ve been coming here since I was a teenager and now I have to knock on the door to get in. I’m now a guest at what was, for so many years, my department,” he said.

“It takes some getting used to, but I get it. This is no longer my place; it is time for me to move on. I’m not a cop anymore.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge