Mr. Long was fired and returns to his workplace armed with a gun, looking for his boss, Mr. Baker. He only finds Mr. Baker’s secretary, who he then takes hostage.

Though this scenario is fictitious and part of a monthly training session for Anaheim Police Department’s hostage negotiation team – the Tactical Negotiations Unit – it’s one, among many others, that negotiators must be trained to handle.

The team of 11 – one sergeant and 10 officers – has a range of hostage negotiations experience (from five months to 20 years) and backgrounds, including patrol officers, a traffic investigator and a sex crimes detective. The common denominators to their work as negotiators are in their communications skills and adaptability.

“It’s really who can think quick on their feet and who can talk,” said Sgt. Steve Pena, who coordinates the team, adding that even more important than talking is “the ability to listen.”

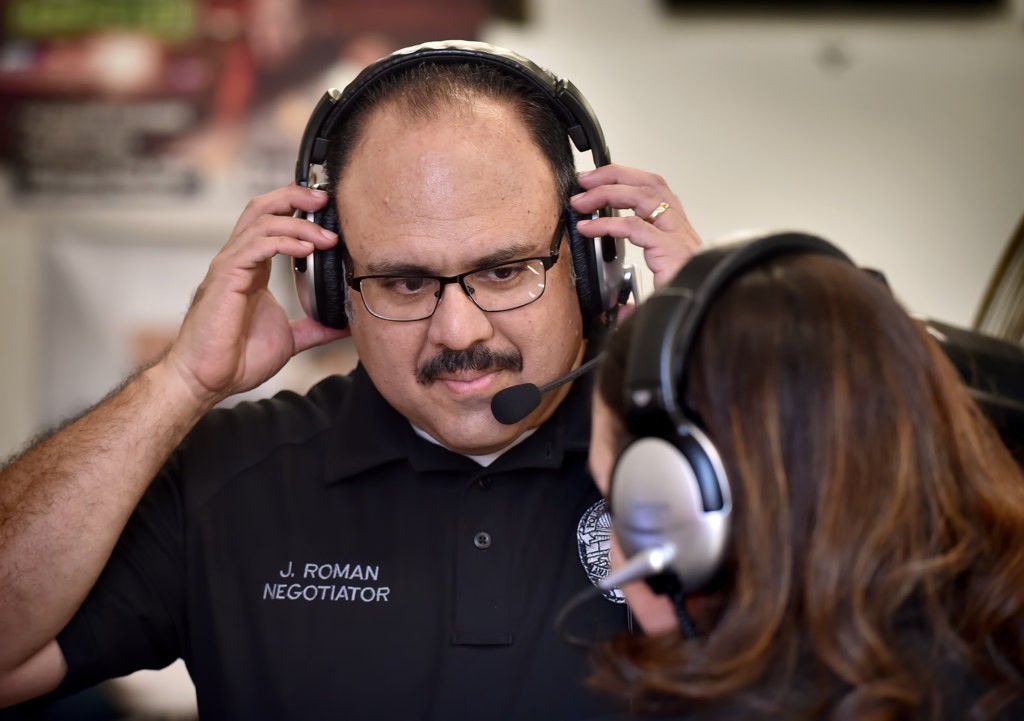

Anaheim PD Officer John Roman, a negotiator for Anaheim’s Tactical Negotiating Unit, participates in a training session.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

As the team recently worked through a training scenario at the APD SWAT Annex building, as part of their day-long monthly training, the importance of team members being able to quickly adapt to changing information also was made perfectly clear.

“You have to be able to switch gears really quickly because things definitely change,” said Officer Alisha Halczyn, who has been a hostage negotiator on the team for 20 years.

As the main negotiator (known as the primary negotiator) spoke over the “throw phone” – a landline phone set in a black box named because of how it is typically thrown into a barricaded room to communicate with a suspect – with Mr. Long (played by Pena), the goal of the team was to keep Mr. Long talking.

Negotiator: “I get you’re upset… I can feel what you’re going through…You got a family that still cares about you.”

Mr. Long: “I don’t want the cops here. I don’t want the media people here.”

(Hangs up.)

Sgt. Steve Pena and Officer Alisha Halczyn work in Anaheim PD’s new NOC (Negotiations Operation Center) vehicle used by APD’s Tactical Negotiating Unit during a training exercise. Once parked, the driver and passenger seats can be turned around to use with a fold-out table that doubles as a white board.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“They’ll hang up on us all the time,” said Halczyn.

Depending on the type of call, the dispatched team can range from a few members to the entire team. The team structure consists of the primary negotiator, who communicates with the subject; the secondary negotiator, who sits alongside the primary to assist with ideas and topics to help guide the conversation; and the team leader, who is the go-between for the primary and secondary negotiators, helping to collect intelligence for them. The rest of the team assists with gathering information from witnesses, family members, etc.

As the training scenario with Mr. Long evolved, the intelligence-gatherers supplied additional information about Mr. Long’s family, as well as the secretary he had as a hostage. Throughout the scenario, the unit would periodically group together to discuss the best direction to take the conversation with Mr. Long.

“We work very closely together,” said Halczyn.

The negotiators have a brand-new, self-contained van (called the Negotiations Operating Center) from which they conduct negotiations. It’s complete with white boards (even the pull-down table top where the negotiators sit is a white board), rotating front seats, padded bench seat and microwave (considering the long hours negotiators must spend in the van).

Officers Kacey Costa and John Roman work with a communications device, often used to talk to hostage takers, during a training exercise for APD’s Tactical Negotiating Unit.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Officers who apply and are accepted to become hostage negotiators attend a 40-hour, week-long hostage negotiator school. In school, they learn the differences between the work of patrol officers and hostage negotiators in dealing with suspects.

“A good cop doesn’t necessarily make a good negotiator,” Halczyn said. “The goal is definitely different.”

The stages of hostage negotiations interaction start at active listening and lead to empathy, which leads to rapport, then influence, ending with behavior change.

“Most cops start right at influence,” said Pena, meaning the officer asks the suspect to do something and the suspect generally complies.

When a suspect doesn’t do what he’s asked by an officer on the scene and the situation escalates, the unit is brought in. The negotiator actively listens by asking questions (What’s going on? How’re you feeling?) and really paying attention.

“People want to be heard,” Pena said.

In another room, Sgt. Steve Peña plays the part of a hostage taker talking to negotiators during a Tactical Negotiating Unit training exercise.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Over the summer, Pena arrived first on the scene of a “bridge jumper” situation at Euclid Street and the 5 Freeway.

“So I just started talking to her,” he said, adding that it took about 30 minutes for her to come down.

He said basic training teaches negotiators that they don’t need to be psychologists to handle these situations. One of the key things is figuring out which category subjects fit: mad, bad or sad.

“Our tactic is active listening skills,” Pena said.

Even though they don’t need to be psychologists, part of their training includes learning from psychologists. In fact, the morning half of this day’s monthly training was a class with the agency’s police psychologist on the medications people take for mental health issues. The medications a suspect may be on (anti-anxiety prescriptions, for example) can affect the approach the negotiators take in speaking with him or her.

In addition to their monthly training, the hostage negotiators also participate in regional quarterly training as part of the California Association of Hostage Negotiators, as well as the association’s annual weeklong conference. And the group trains annually with APD’s SWAT and sniper teams.

Officer Alisha Halczyn, a negotiator with Anaheim PD’ Tactical Negotiating Unit, talks about training and tactics used by the team in dealing with situations such as hostage takers and potential suicide jumpers. Behind her is the department’s new NOC (Negotiations Operation Center) vehicle.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“As a county, we work together, utilize other agencies if need be,” said Halczyn.

The role of the negotiators in a real-life scenario is to slow things down to keep a suspect or suspects from escalating the situation.

“Time is always on our side,” said Pena.

Hostage negotiators get to know suspects in ways other officers do not. And it’s that emotional involvement and rapport that help hostage negotiators get suspects and their hostages out safely.

“You get to know these people in a different way,” said Officer Kacey Costa, who has been on the team for 16 years. “You definitely see them as human.”

She recalled a barricaded suspect who surrendered to police after negotiations and requested that she hold his hand while he was handcuffed. She did because it’s important for the negotiators to maintain that rapport – especially since it might serve them in the future.

“We’re kind of that face [of the agency]and we set the tone for future contact,” said Halczyn of the potential for repeat offenders.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge