When La Habra Police Department Burglary Det. Jason Willard gets an email with the subject line: “CODIS Hit,” he knows his case is heating up.

The FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) uses DNA evidence to help law enforcement officials reduce their list of possible suspects to one.

Here’s how it happens: Weeks and sometimes years earlier, DNA is left at the scene of a break-in or other crime. Crime scene investigators or police officers gather the DNA, and then the Orange County Crime Lab processes the DNA. When the evidence comes back with a hit from CODIS, cases that had no identified suspect heat back up.

“It is proof positive,” Willard said about why DNA evidence is such an effective tool. “It will only match one subject.”

Once notified of a DNA hit, Willard writes a Ramey Warrant and a DNA Warrant on the identified suspect. The Ramey Warrant is entered in the system, and then any contact the suspect has with law enforcement will trigger an arrest so the suspect can be interviewed about the case.

Once the person is in custody, the DNA Warrant allows for a comparison sample of their DNA to verify the DNA hit. Often, suspects are found in other cities, so it is common for Willard to go to the arresting agency to conduct an interview.

“If the suspect wants to talk to us,” Willard said, “we’ll interview him, and that’s where our skills come in. We create a rapport with him and get them talking. But if he says he wasn’t there, the DNA located at the scene is proof positive. There’s no other excuse.”

At least half of Willard’s cases involve some type of DNA evidence.

“DNA can be anywhere,” he said. “Suspects will usually unknowingly leave some type of DNA evidence behind.

“Most of my DNA submissions come back with a hit. When something comes back, it’s exciting. I love what I do,” Willard said.

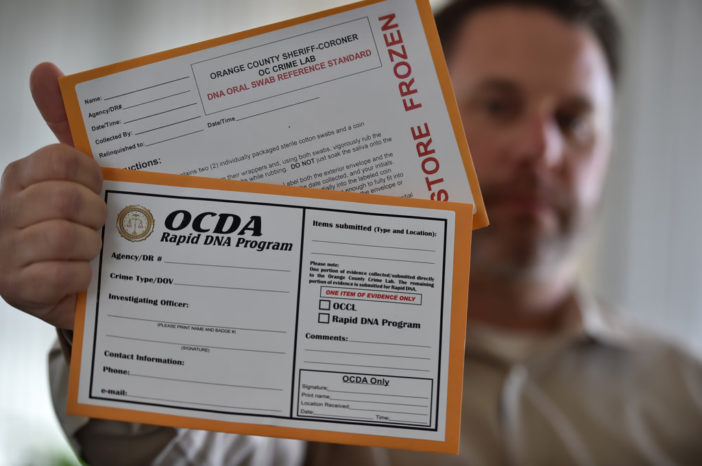

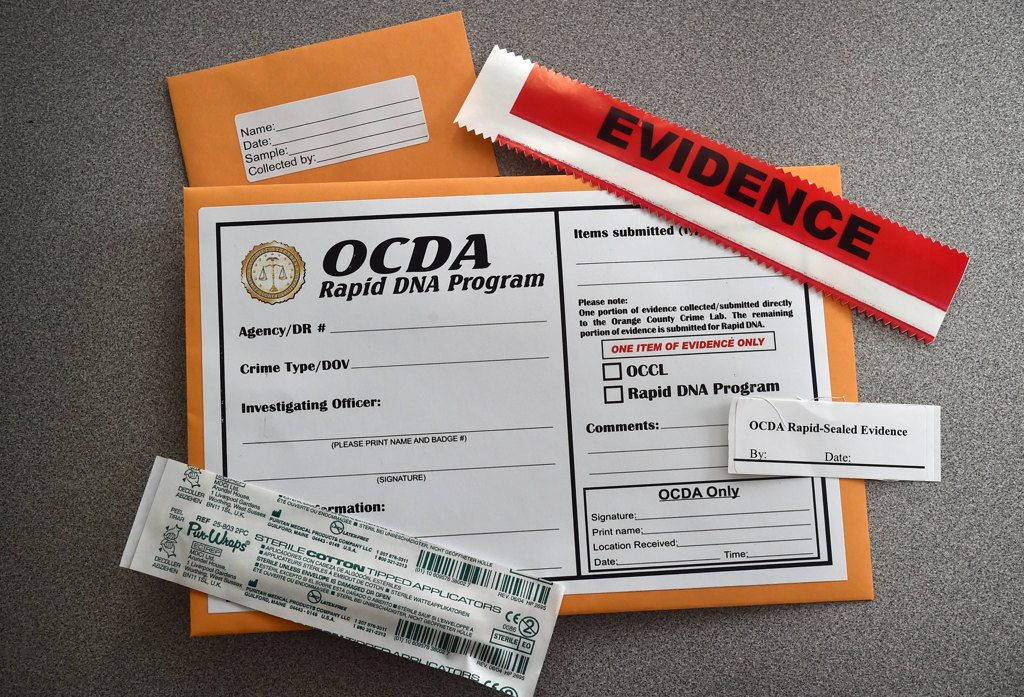

An OCDA Rapid DNA Program kit is used for collecting and the proper storing of DNA samples to be sent to a special lab for quick results.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Then, there are the cases DNA cannot solve.

“Sometimes it is disappointing if something is cross contaminated,” Willard said. “Cross contamination occurs when an item is touched by more than one person. When an item has been touched too many times, the results are more challenging.”

He added: “Working property crimes, you have to put the puzzle together. We have to be creative and collect evidence that is likely touched only by the suspect.”

As Willard explains, DNA evidence can be used as the foundation of a case, or DNA can be the piece of evidence that pulls everything together. Each case is different, based on a distinct set of circumstances.

Willard remembers a pharmacy break-in a year ago, when DNA collected at the scene led the investigation. The suspect tunneled through the drywall of the business next door and used a crowbar to pry one of the shelves. Crime scene investigators swabbed evidence and, three months later, a suspect with a previous burglary record came up as a match in CODIS. At the time, the suspect was in custody in Los Angeles County on another charge. Shortly after, Willard obtained a DNA Warrant and the suspect’s comparison DNA was collected. The DNA matched. The suspect pled guilty to the burglary, Willard said.

In another example, the only evidence collected after a liquor store robbery in December 2016 was one fingerprint. The fingerprint contained DNA, and a hit returned a few months later. Willard interviewed the suspect after he was arrested. He took a comparison swab of the suspect and the DNA matched. Willard was able to file charges, and the case is pending.

In a more high-profile case, more than $120,000 worth of devices was stolen from a cell phone store during a nighttime burglary. The case involved a police pursuit that spanned two counties, with one of three suspects arrested at the end of the pursuit. The La Habra Police were not only able to retrieve all the stolen items, but were able to identify the other suspects using DNA. A combination of DNA evidence left in the suspect vehicle the night of the burglary, along with video surveillance footage, helped bring that case to a close.

Cases involving DNA take time, and if there’s one thing that frustrates Willard, it’s that even with the gift of solving crimes using DNA evidence, it couldn’t be fast enough. Using DNA evidence is not as fast as it looks on TV.

“We do everything we possibly can,” Willard said. “TV can create a false sense of what is actually doable. TV is for entertainment. In real life, crimes cannot be solved in 42 minutes plus commercials. As much as we want to catch these guys that fast, it’s just not possible.”

Suspects often don’t live in or near La Habra. But when the OC Crime Lab shares information with the LA Crime Lab or others, officials can reduce the list of possible suspects to one. With an interview and DNA comparison sample, it can be another case closed with a suspect identified.

That’s the way Willard likes it.

“It’s nice to know after all the work you do, this is the guy,” Willard said. “That’s a good day.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge