Editor’s note: In honor of Behind the Badge OC’s one-year anniversary, we will be sharing the 30 most-read stories. This story was originally published Dec. 4, 2014.

On the night his life would forever change, Brent Wisdom dressed up as a cop.

It was Halloween 2009.

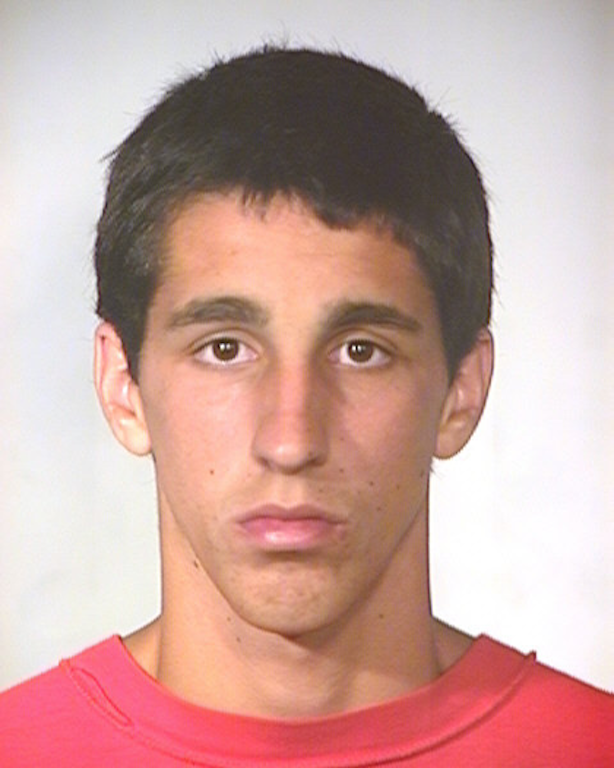

Wisdom, then 17 and a three-sport athlete and honor’s student at Rancho Alamitos High School in Garden Grove, always wanted to be a police officer.

Then, at 1:04 a.m. Nov. 1, a real-life horror unfolded — one that sent Wisdom on a long, gut-wrenching journey of grief, self-loathing and, ultimately, redemption.

“As much as I think it was an accident,” says Wisdom, now 22 and pursuing, against considerable odds, his dream of becoming a cop, “I know I still could have avoided it.”

***

He wanted to show off in front of his friends.

Wisdom had a sweet ride — a cherry-red, 1994 lifted Suburban — and three fellow minors in need of a ride home just after midnight, including a close friend, 17.

He also only had a provisional driver’s license, meaning he was forbidden from driving minors unless an adult was in the car.

Plus, it was past curfew.

Wisdom’s mother, however, was not available to taxi the teens home. So with her reluctant permission, Wisdom and his passengers — ages 14, 16 and 17 — piled into his tricked-out SUV for what should have been a 20-minute round trip.

None of the minors, including Wisdom, had been drinking or doing drugs.

All were tired from the Halloween party at Wisdom’s uncle’s house.

But Wisdom was pumped for a little late-night fun in his SUV.

***

In addition to being a second-team All League football wide receiver and basketball player, Wisdom was a baseball player and member of his school’s vocal ensemble.

His GPA was 3.5.

He didn’t party.

But he was no saint.

Earlier that month, the incoming senior had been arrested by the Garden Grove PD for throwing objects at moving vehicles.

Sure, Wisdom had done some stupid things.

But nothing like what happened that Halloween night.

***

Both carloads full of teens were heading home from separate Halloween parties.

Wisdom, in his Suburban, had done it before: gunned through dips in the street to get some air.

He decided to try it in an alley off Brookhurst Street and Orangewood Avenue in Garden Grove.

He had zoomed down that alley before, too — as had many other teen drivers in the area, according to police.

As Wisdom barreled west down the alley, which is parallel to Orangewood and crosses two streets — both blind intersections — 18-year-old Roxana Covarrubias was traveling north on Faye Avenue in a white 1992 Toyota Corolla.

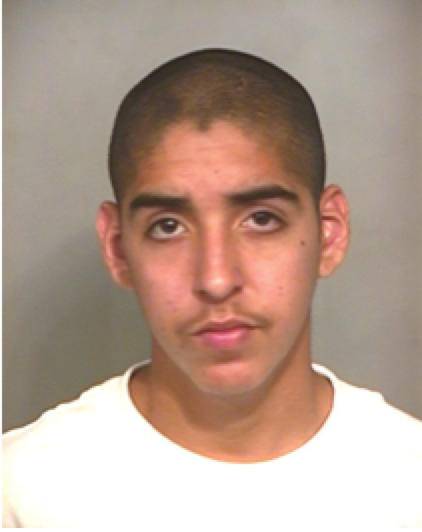

Sitting in the front passenger seat of Covarrubias’ car was Erick Hernandez, 19, a father of a small child. In the back seat was Covarrubias’ 15-year-old sister.

Hernandez had multiple contacts with Garden Grove police as a professed member of the SOG (Soldiers of Graffiti) tagging crew.

His graffiti gang pals, some who attended Rancho Alamitos High at the time, nicknamed him “Wako.”

Wisdom intentionally blew through the intersection at Faye Avenue at around 30 mph.

Then came the sickeningly violent sound of metal-on-metal.

The scene after the early Nov. 1, 2009 crash in an alley at Faye Avenue in Garden Grove. Photo Courtesy of GGPD

***

When he crawled out of his SUV, his head hurting, Wisdom saw the white Corolla flipped over on its roof.

A bloodied young female — Covarrubias — struggled out of the Corolla.

Wisdom helped her to the curb and called 911.

Master Officer Jason Perkins, the lead traffic investigator on the scene, tried to calm Wisdom.

Soon, Perkins told the teenager the tragic news: Hernandez, the teen in the front passenger seat of the Corolla, had died at a hospital after being whisked away from the scene in an ambulance.

“I literally fell down and started balling,” Wisdom recalls.

Perkins, now assigned to patrol, says of the 35 fatal crashes he’s investigated in his years as a traffic investigator, this was one of two he’ll never forget.

“I remember interviewing Brent at the collision scene,” Perkins recalls. “I’ll never forget his reaction when I told him a passenger in the other vehicle had died. He immediately fell to his knees and was in tears.

“I assured him that he was going to go home to his parents that night and that we would be in touch with him in the days that follow.

“He interrupted me and said he wasn’t worried about what was going to happen to him, but that he was upset that he had just killed someone.

“I was surprised to see a 17-year-old with such deep remorse. He immediately took responsibility for his actions.”

Covarrubias, the driver of the Corolla, suffered a fractured pelvis, cracked vertebrae and cuts and abrasions to her legs, hips and head.

Her sister suffered major facial trauma including broken teeth, facial lacerations and an injured jaw.

Wisdom and his passengers escaped with minor or no injuries.

***

For three days, Wisdom didn’t eat. He fainted during warm-ups for a football game.

For a week, he didn’t sleep.

Guilt ate away at him.

His girlfriend dumped him.

“I don’t really remember that first month,” he says.

Some of Hernandez’s friends threatened him. He missed several days of school because of the threats, and once was assaulted.

His grades plummeted, but he finished the school year.

Wisdom’s family reached settlements with victims of the crash as the criminal case against him worked its way through the courts. Wisdom was charged with failure to yield, driving at an unsafe speed, provisional violations, and — the biggie — manslaughter.

But was it felony or misdemeanor manslaughter? Did Wisdom show gross or “ordinary” negligence that night?

The prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney Susan Price, thought the crime rose to the level of felony manslaughter with gross negligence.

Price was fresh from the highly publicized trial victory that put the drunk driver who killed Angels pitcher Nick Adenhart (and two of his friends) behind bars for 51 years to life.

Price also was one of the founding members of the D.A.’s Vehicular Homicide Unit, a special group of prosecutors that only deal with fatal collisions. She wanted to put Wisdom away for nine years in the state Division of Juvenile Justice for killing one and injuring two.

“I felt that punishment was too harsh,” Perkins recalls. “I shared this opinion with Susan, and it created tension between us. I respected her opinion but I just disagreed with it. I lost a lot of sleep over this case.

“I didn’t think this kid deserved to go to jail for nine years. I recognized the tragedy of the preventable loss of a young life, but I had seen drunk drivers sentenced to less jail time than this in my career.

“Brent’s mom would call me almost every day for months, asking me if her son was going to jail. The best answer I had was, ‘I don’t know.’

“Susan eventually settled for the court’s recommended sentence of three years of probation and 200 hours of community service. In the end, I think an appropriate sentence was reached. Even Erick Hernandez’ family was at peace with the decision.”

After the final court hearing, Wisdom recalls speaking to Hernandez’s mother.

“She covered her eyes,” he said. “She told me, ‘Nothing you say will bring back my son, but you remind me of him. You need to live your life for him.

“I want you to know I don’t blame you.’”

***

Wisdom says hearing those words from Hernandez’s mother helped him immensely.

While the case was being adjudicated, he would write letters to Hernandez’s mother, expressing his remorse, only to crumple them up and not mail them.

In a unique move by the courts, Wisdom was assigned to Perkins for his community service. More than half of the 200 hours came in the form of him speaking to many schools and community groups about teen driver safety, delivering a Power Point demonstration that included photos of the crash scene.

“Brent had to tell his story over and over again,” Perkins says.

“Each time he did, he broke down in tears. It was difficult to watch. His mom told me he would never talk about it at home. He would only talk about it in these forums. I think reliving the crash over and over again was punishment enough for him.”

Says Wisdom: “I hated talking about it. Every time, I’d relive it. But the second I would finish each presentation, I would feel so relieved.”

The nightmares, in time, became less frequent.

After Wisdom successfully completed his community service, his crime was reduced to a misdemeanor.

His involvement with Officer Perkins was so successful that Perkins had another teen driver convicted from another city assigned to him to complete a similar program.

***

These days, Wisdom is working two part-time jobs and majoring in criminal justice at Cal State Fullerton. He hopes to graduate in December 2015.

He has applied to a handful of law enforcement agencies. As a requirement, he must disclose his misdemeanor conviction. One agency turned him down because of “background issues,” he said, but the other two still are pending.

Wisdom still remains in touch with Perkins from time to time.

“I am supporting him in his efforts to become a law enforcement officer,” Perkins said.

On the five-year anniversary of the crash, Wisdom sent Perkins the following message:

Hey Mr. Perkins. I just wanted to say thank you. You were there for me in my darkest hour. As tough as this day is for me and my family, the one thing that helps is knowing people like you are out there. You, along with my family and friends, are the reason I am where I am today. I can’t tell you how grateful I am for everything you have done for me. I miss ya, and I hope everything is well.

Wisdom knows his background is a significant roadblock to becoming a cop, but he believes his experience would make him a good one.

“One officer told me, ‘I will try to do everything I can to get you hired. I think you’ll be a great officer.”

For now, though, he wants all teens — all drivers, in fact — to hear his message loud and clear.

“Don’t treat your vehicle like it’s a toy,” Wisdom says. “One split-second decision can impact your life forever.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge