Big in stature and even bigger in personality, Chief Raymod Davis cast a shadow over the Santa Ana Police Department and enacted policies that still echo today, more than 30 years after he retired.

Davis, who served at the helm of the police department in Orange County’s second-largest city, died Thursday, March 29.

From his stances on immigration enforcement, to community policing and civilian participation, Davis was a trailblazing firebrand.

Although Davis liked to say courtesy begets courtesy, he also wasn’t about to back down when challenged, particularly if he felt the opposition was factually wrong or lacked the moral high ground.

And at 6-foot-5 and 300 pounds, he was an imposing figure that belied his usually calm demeanor.

“He had a huge influence on the department, on its character, its direction and professionalism,” said Paul Walters, the chief of the bureau of investigations for the Orange County District Attorney’s office. Walters was an officer under Davis and eventually succeeded him as chief from 1988 to 2013.

“He set the foundation,” Walters said. “I just built on top of that.”

During his 14-year tenure as police chief that started in 1973, Davis earned national recognition, as well as backlash, for his policies.

“When I think about Chief Davis, I feel he was a visionary and innovator,” said Joe Vargas, a retired Anaheim Police Department captain.

Vargas’ father, Jose Vargas, was one of Davis’ early hires. The police chief recruited Jose Vargas from the Stanton Police Department and together they created the city’s first Hispanic Affairs officer position.

The hiring of Jose Vargas brought its own level criticism, as Vargas entered the country illegally and had been deported a number of times before he became a citizen and police officer.

However, Jose Vargas also brought a special empathy and understanding of the Latino community.

“Ray Davis would say he was worth 10 officers,” Walters said of Jose Vargas, who was a recipient of the Police Officer of the Year from the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

Davis’ approach to immigration drew widespread attention. In 1983, in a decision that echoes today, he publicly announced his department would not cooperate with the federal authorities in their sweeps through the city.

Walters said his mentor’s stance on immigration enforcement was often misunderstood and misstated.

The chief was not soft on undocumented immigrant crime, but saw random sweeps and voluntary deportations as illegal and ineffective, with deportees often returning within days of their expulsions.

Walters said he remembers as an officer on graveyard shifts he would often watch undocumented people jump off trains to waiting taxis. Police would follow the taxis to a network of houses that temporarily sheltered them, then arrest everyone.

That practice ended when Davis took over.

According to Walters, Davis took his arguments against the legality of random sweeps all the way to the attorney general.

“He took a lot of heat for that stance,” Walters said.

Davis was also on the leading edge in a number of other areas of police practice.

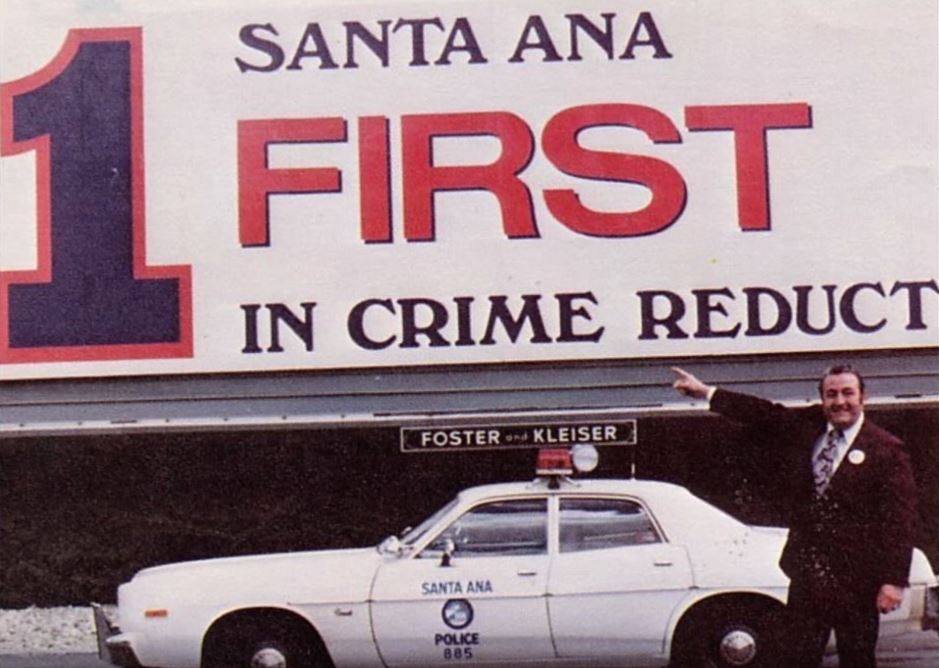

“Chief Davis was an exceptional leader and pioneer in community policing strategies, when this philosophy was in its infancy in the 1970s,” said current Santa Ana Police Chief David Valentin in a statement. “Chief Davis led our department to an unprecedented reduction in crime (and) revolutionized our department’s service, which was based on treating everyone equally.”

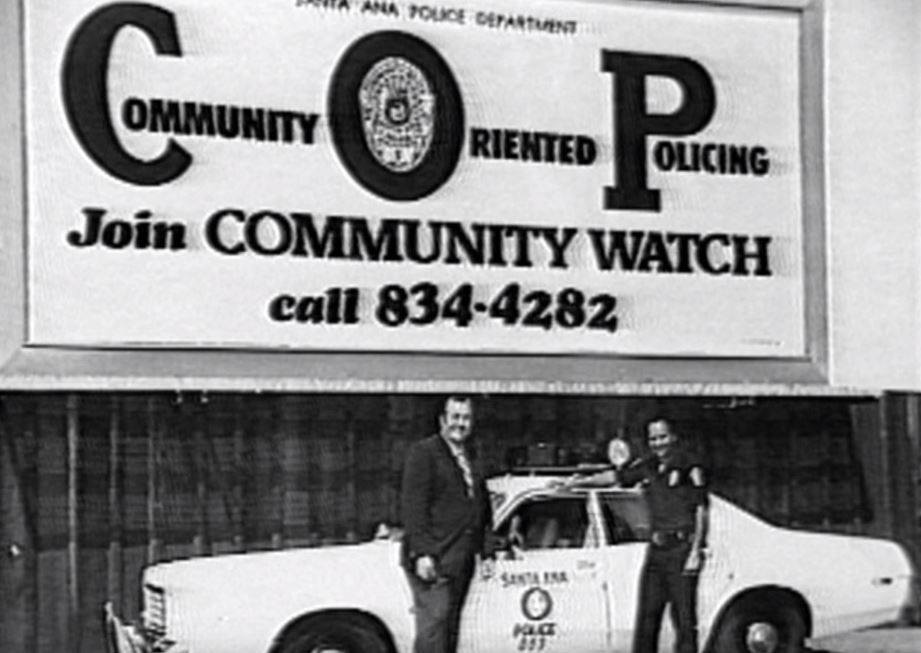

Davis introduced community policing to Santa Ana — called “team policing” at the time — with teams assigned to specific areas of town and stressing foot patrols, community involvement and outreach.

Davis was also instrumental in getting the city council to raise taxes to hire 88 officers and 10 civilians. He also succeeded in saving money by hiring civilians to take over clerical and administrative positions to allow more cops to be on the street.

Santa Ana was also one of the early cities to embrace civilian neighborhood-watch style programs.

Davis’ innovations led Santa Ana to be featured by “60 Minutes” in a 1982 segment about community policing in several U.S. cities.

Despite his reputation as a darling of progressive policing advocates, Davis was “a strong disciplinarian and really held officers accountable,” Walters said.

Walters said Davis helped transform the department “from old school to a new professionalism.”

As often happens with agents of change, Davis drew his share of opponents. In 1983, 63 percent of officers in the Santa Ana Police Benevolent Association voted no confidence in the chief. However, according to the Los Angeles Times, the same day the vote was announced, a news conference was held by civic leaders to show community support for the chief.

Beginning his police career with the Fullerton Police Department in 1954, Davis rose to the rank of captain before moving to Northern California to become the police chief of Walnut Creek in 1964. He returned to his Southern California police roots and was named Santa Ana’s top cop in 1973.

Among his accolades, Davis was a chairman of the California Council on Criminal Justice and named police chief of the year by the California Trial Lawyers Association.

Some of Davis’ proteges, like Walters, are still coming to grips with the loss of a man who they say transformed their lives.

“I guess I loved him more than I could ever express in words,” Walters said.

Services are scheduled Wednesday, April 4, at Brown Colonial Mortuary, 204 W. 17th St., Santa Ana. Viewing from 10-11 a.m., service from 11 a.m.-noon with a flag folding and honor guard presentation at noon.

A reception will follow at Avila’s El Ranchito, 2201 E. 1st Street in Santa Ana. Gravesite services will be conducted in Fentress County, Tenn. at a later date.

To view Davis’ 1984 C-Span interview, click here.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge