The new patrol deputy and father of two had 30 minutes to go until the end of his shift.

He had dinner plans with his wife.

It was Mother’s Day.

Todd Hylton has replayed that day — Sunday, May 8, 2011 — countless times.

And, as a kind of therapy, he’s told his story the past few years at an OCSD Citizen’s Academy class.

On Thursday, July 19, Hylton, 38, told the story again.

This time, for once, he didn’t break down.

Several times, though, he came close, his tale a harrowing example of how, in a flash, a patrol deputy’s day can careen from routine to horror.

MOVED TO TEARS

The 47 students in this year’s countywide OCSD Citizens’ Academy didn’t know what was coming.

They had just toured patrol vehicles belonging to a handful of O.C. law enforcement agencies at the Orange County Regional Training Academy, where most of the three-hour academy sessions are held over nine weeks.

Several times during Hylton’s 20-minute story, many Citizens’ Academy participants, who sign up to learn about OCSD operations, gasped.

Some teared up.

Hylton’s tale underscores a reality of law enforcement many members of the public likely don’t think about — “how things can go from bad to worse to good like that,” Hylton said, snapping his fingers.

On Mother’s Day 2011, he was less than five months into his new assignment as a patrol deputy covering unincorporated areas of north O.C.

“I was kind of still sort of trying to learn the ropes,” said Hylton, who before that worked jails for 5 ½ years.

That day, his sergeant told him at the start of his shift to be nice to mothers and only write tickets if they really deserved it.

“I have a 3-year-old son at home and a 6-month-old at home, and 30 more minutes until my shift ends,” Hylton said.

Then, at about 5:30 p.m., his radio crackled with the dispatcher’s voice.

A male teenager said his mother just shot him and his father, and was firing at his younger brother still in the house.

“I thought someone was pranking me,” Hylton said.

First on the scene, he approached the house in the 18400 block of Manning Drive.

For a moment, all was quiet. Then a woman ran toward him from a side street, holding something.

“Here I am yelling at her and within about half a second, I make a judgment that she’s not a threat,” Hylton said. “I don’t know what’s in my mind, but I could tell she wasn’t a threat. In her hand was a cordless phone. She’s screaming.”

Hylton’s partner, a SWAT deputy, shows up.

Approaching the house, Hylton sees a kid come out the front door holding a gun.

“This thing looked like a hand cannon in his hand,” he said. “It’s Mother’s Day, and he’s running at me with a giant gun in his hand.”

Looking at the boy between the sights of his service weapon, Hylton yells at the boy to drop the gun.

“I don’t like to cuss, but I probably said every cuss word in the book,” Hylton said.

His partner, aiming his rifle, also pleads with the boy to drop the gun.

“You’ve seen those scary movies and they show the audience with fear in their eyes?” Hylton said. “You haven’t seen pure horror until it’s looking back at you from the eyes of a 9-year-old kid.”

The boy stops in the driveway and drops the gun, a .44 magnum Blackhawk — a six-shot, single-action revolver.

“That kid, that look, I’ll never forget it,” Hylton said. “It’s not fear. It’s horror.”

OCSD Dep. Sgt. Todd Hylton tells his harrowing story to an OCSD Citizen’s Academy class at the OCSD Regional Training Academy.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

The boy runs into the arms of the woman who came from the side street — a neighbor, of Filipino descent like the boy — and they disappear down the street.

Ten seconds later, Hylton and his partner enter the open front door.

“All we hear is what sounds like the sounds of death,” he said. “It sounds like people taking their last breath.”

Two Tustin PD officers show up.

Hylton sees blood splatter on an open sliding glass door to the backyard.

In a room down a hall, he finds two adults on the floor “basically embracing.”

“I don’t know what’s going on,” he said, “but there’s a pool of blood around them. They’re both covered in blood.”

One is a male with a gunshot wound to the chest, dying.

The other one is a bald, very slender woman.

“I can tell she’s not quite (conscious), so I kind of give her a little nudge. Her eyes roll back down. All I say is, ‘Who did this?’ She looks up at me and says, ‘I did. I did. Please kill me.’”

Her eyes roll back in her head, and she’s out.

Hylton remembers the blood on the sliding glass door.

He realizes the 911 caller — a 16-year-old boy — is missing.

He follows a trail of blood out the back door. It goes down the street to a house. There’s a pool of blood on a doorstep.

Inside is the woman who was holding the cordless phone; the 911 caller, who suffered a non-life-threatening gunshot wound to his arm; and his brother — the kid who ran out of the house holding the gun.

The 9-year-old is physically unharmed.

Hylton described to the Citizens’ Academy class the agony he felt.

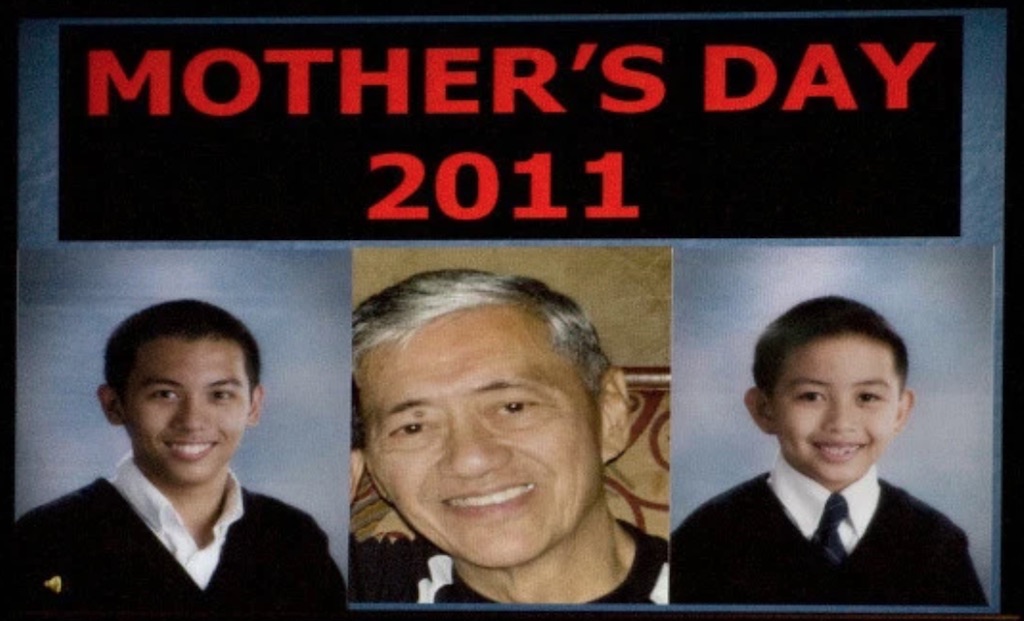

Fatal shooting victim Antonio Potenciano Gana (center); his 9-year-old son (right), the boy Sgt. Hylton saw coming out of his house with a gun; and the boy’s 16-year-old brother. The shooter, Annamaria Magno Gana — Antonio Gana’s wife — also tried to kill their sons. She is serving 40 years to life in prison.

“I’ve never fired my gun on duty, and I hope to God I never have to,” said Hylton, now a sergeant in the OCSD’s Mutual Aid Bureau, which is within the agency’s Homeland Security Division.

“If that kid would’ve raised that gun, I don’t know what I would’ve done.”

THE FACTS EMERGE

The facts of the incident emerge.

According to a court document, Annamaria Magno Gana, then 41, was at the time of the shooting a cancer survivor receiving chemotherapy and also taking Ambien to help her sleep.

In addition, she was under stress from the financial problems of operating a business that was not doing well.

She and her husband, Antonio Potenciano Gana, 72, were attempting to sell the business, but she was concerned the sale would not occur. Gana claimed to be overwhelmed with everything that needed to be done.

For weeks before the shooting, she claimed to have suicidal thoughts and developed a plan to kill her husband and children — Tony, 16, and Alfonso, 9 — before taking her own life, according to the court document.

At trial, Tony Gana described the shooting as follows:

I heard this loud noise. Alfonso yells that it was a gunshot. And then my dad gets up, runs to the [bed]room, Alfonso and I right behind him.

I stop at the doorway, my dad rushes in, and I see my mom holding a gun.

[T]hen [my Dad]tries to grab the gun from her.

I see him get shot, and Alfonso and I run away.

I reached the kitchen, but then I stopped, because I didn’t believe that it was real.

I turn around, I see Alfonso hiding behind one of the couches, and then I see my mother chasing after me with a gun.

I yell at her don’t shoot, then she shoots me, and I fall to the ground.

I hear another gunshot, I thought it was for me, but it wasn’t.

Then I see Alfonso taking away the gun from my mom, and that’s when I run out and called 911.

Alfonso testified that after his mother shot and wounded his brother, he saw her point the gun at her head and fire it. The bullet grazed her neck.

She then started crying and saying, “ ‘What – what did I do?’ ” Alfonso then picked up the gun from the floor and left to find his brother.

That night, Alfonso ended up at Orangewood Children’s Home until relatives from the Philippines came to Orange County to take care of him and his brother.

In April 2013, Gana was convicted of murdering her husband and attempting to kill her two sons.

In June 2013, Gana, then 43, was sentenced to 40 years to life in prison for the murder and lesser, concurrent terms for each of the attempted murders.

‘THAT’S A BAD DAY’

The night of the shooting, Hylton’s wife’s mood quickly went from anger and disappointment about him missing Mother’s Day dinner to worry and concern.

“All she cares about is me,” Hylton said in describing a quick phone call they had after she learned about the shooting on TV. Until then, he hadn’t had the time — or heart — to tell her what had happened.

“That’s a bad day,” Hylton, who grew up in Costa Mesa, told the class. “That’s what we go through on a bad day.”

He added: “We were talking (earlier) about how cops can be jerks sometimes. Yeah, we can, we really can. But you go to that call where you got a mom and dad that are beating a little kid, and then you pull over a guy who’s drunk and he starts (yelling at you).

“I’m a human being. I have emotions. I just went through a rollercoaster with these parents on this call and now I have some 21-year-old drunk guy who obviously shouldn’t be driving yelling at me. We lose our cool. We do. We’re paid to be professional. And we try to be. But at the end of the day, we’re human. We make mistakes just like everybody else, and we own up to them when we do.”

OCSD Citizens’ Academy participant Katie Grove, of Rancho Santa Margarita, said she didn’t think she was going to be getting teary eyed at the end of the night, but Hylton’s story affected her that much.

“The raw emotion he tells the story with is captivating,” Grove said. “It’s hard listening to stories like that on TV, but listening to it in person from the person it happened to is way different. You can tell that there is not a day that goes by that he doesn’t think of that story, especially all these years later.”

Another participant, Joanne Hubble, of Modjeska Canyon, signed up for the Citizen’s Academy to learn as much as possible about the OCSD to better help her community.

“I work very closely with them quite often for canyon-related emergency incidents, and knowing more of the inner workings will only help me to improve my services for the residents of the canyons,” Hubble said.

Her daughter also works for the OCSD, and Hubble wanted to learn more about what she goes through on a daily basis so that she can better understand what she does and what she sees, and to be there for her.

“I can feel the tears running down my cheeks as I remember his words,” Hubble said nearly a week after Hylton’s talk.

“My biggest takeaway was learning that a support system for the deputies outside of work is paramount,” she said. “These folks are trained to put up a tough front on the outside in any given situation, even if they are terrified or horrified or crumbling on the inside. They see things and go through things that no one else does, and most of the time they don’t open up to their family members or friends because they’re afraid that they won’t understand. I don’t want that for my daughter. I want to be there for her – for whatever she needs and whenever she needs it.”

Said Grove: “I definitely learned that it’s easy to say what you would do in any given situation, but when you get put in a life-or-death situation, how different actions can be. It’s easy for people to judge someone else’s actions, but actually being put in that same situation is a different story.

“Sgt. Hylton is a brave man not only for his career and putting his life on the line every day to make sure our community is the best it can be, but he’s brave for telling his story to help us civilians see that this job is not easy.”

Hylton said the OCSD does an “amazing” job with peer support and related programs to help deputies and other personnel maintain their physical and mental well-being.

“I have a beautiful wife,” he added. “I have two great kids and they support me. I have a great job with the (OCSD). I’ve been through a lot of ups and downs, and that’s what happens. We get in our car (as deputies), we think we’re invincible, and we go through these things on our shift. And that was one day.

“And this is just one story from one deputy. Every (deputy) has that one call that they carry with them that they’ll never forget.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge