It’s 7 a.m. on a recent weekday, and three members on a specialized Anaheim PD unit already have their hands full.

But when your job is to help the mentally ill, that’s the norm.

Faced with a shortage of mental health beds, the influx of more offenders on the street due to legislation such as Prop. 47 — which converted nonviolent offenses such as drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors – along with a chronic housing shortage, Orange County law enforcement agencies increasingly are responding to calls involving the mentally ill, many of them homeless.

One of the most proactive agencies is the Anaheim PD. The agency was among the first in O.C. to address the burgeoning mental health and homelessness crisis when it formed PERT, for Psychiatric Emergency Response Team, in October 2013.

Although several other O.C. law enforcement agencies have followed suit, the APD remains the only local municipal law enforcement agency that dedicates four full-time officers, paired with two full-time mental health clinicians, to assist the mentally ill. The clinicians are employees of the Orange County Health Care Agency, and address acute incidents in the field as well as perform case management for those suffering from chronic mental illness in Anaheim.

Current team members include Sgt. Mike Lozeau; Officer Matt Beck, who has been on PERT from the start; Officer Steve Voss, on the team for three years; mental health clinician Mari Tafoya; and mental health clinician Christina Numamoto, of the OC Health Care Agency. Two additional officers are working overtime until the full-time positions can be selected.

“If we fix our mental health system, it will be a huge step toward solving the homeless problem,” says Beck.

It’s a daunting challenge, but one Beck and Voss are up to addressing, one field contact at a time.

“It’s a part of policing where you can actually make a difference nowadays,” Beck says. “We know we can’t arrest our way out of the problem, and with our work with PERT we can see the difference we make in these people’s lives every day.”

Says Voss: “We actually get to see that we’re making a difference.”

An Oct. 3 ride-along with Beck, Voss and Tafoya — a week before National Mental Health Day, on Oct. 10 — proved to be typically busy and eventful.

Anaheim PD Officer Stephen Voss (left) and Officer Mathew Beck talk to a couple living in Maxwell Park as they encourage them to seek the services of a shelter.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

DAUNTING NUMBERS

Voss and Beck throw out some numbers.

Between 2015 and 2016, Anaheim PD officers saw a 36-percent increase in the number of mental health-related calls for service, to 2,707. There were about 15,500 calls for service related to homelessness in 2016, and the number of homeless reached 936 on Jan. 28, 2017 for the North County SPA (Service Planning Area), according to a point-in-time count.

With one of the main goals of the program to reach those in need before they are in mental crisis, in 2016 the APD PERT team made 408 contacts, including follow-up and mental health outreach. They also wrote 168 mental health holds. When a person, as a result of a mental health disorder, is a danger to others, or to himself or herself, or gravely disabled, he or she may be taken into custody against his or her will.

The hold commonly is known as a 5150, which refers to a section of the California Welfare and Institutions Code that resulted from the Lanterman–Petris–Short Act, or LPS, which allows people to initially be held for up to 72 hours for assessment and evaluation.

APD patrol officers not assigned to PERT wrote an additional 745 mental health holds in 2016.

With only 484 beds throughout Orange County reserved for mental health patients, and only 10 beds at the county’s designated facility (the Crisis Stabilization Unit), many people put on 5150 holds soon end up back on the street — only to be arrested again for various offenses.

“By far the most frustrating part of this detail is seeing the same people over and over again in the same state we saw them when they were taken to the hospital,” says Voss.

“Often, social workers have no choice but to dispatch them back into streets,” Voss adds. “They can’t force them to take their meds, and getting them to become stabilized on the streets is difficult.”

Says Beck: “The system expects the mentally ill to advocate for themselves, but they don’t have the competency to do it.”

So the APD officers, along with mental health clinicians like Tafoya, do what they can.

A man threatening to jump walks the fence on a bridge over the 57 Freeway as Anaheim PD officers try to talk him down.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

FREEWAY JUMPER

The transient in the cell was a familiar face.

The man, 34, a paranoid schizophrenic and repeat APD arrestee and methamphetamine user, had been arrested early Oct. 3 for possession of drug paraphernalia after someone reported him acting erratically in an alley on State College Boulevard.

Tafoya, a mental health clinician for more than three decades, talked to him through the food port of his cell.

He was malodorous and disheveled, and didn’t know when he last ate or what he had eaten.

PERT’s purpose is to be a field-based assistance provider to people with mental health issues.

This mission takes PERT members to the street, to hospitals, to homes – and to jails.

When the need is care at a mental or health care facility, PERT provides transportation and facility processing and arranges follow-up care to ensure linkage to ongoing services.

PERT also responds to CAT calls that come into Anaheim. The county Centralized Assessment Team, of which Tafoya is a member, responds to homes, police stations, health clinics, private doctors’ offices, therapists’ offices and in the field.

It’s clear to Tafoya that the man in the APD cell needs to be hospitalized.

An Anaheim PD officer and crisis negotiator is consoled by fellow officers after a person he was trying to negotiate off of a freeway bridge fell to the freeway. The man survived the fall with serious injuries.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Voss and Beck call an ambulance to transport him to Anaheim Global Medical Center, which along with St. Joseph Hospital of Orange, UCI Medical Center in Orange, and OC Global Medical Center in Santa Ana are designated facilities for Anaheim mental health patients.

The man’s family wants him in a board-and-care facility since he threatens relatives when he goes off his meds, Tafoya says.

At Anaheim Global, Tafoya follows up with a man taken into custody the night before for being suicidal. He had consumed a bottle-and-a-half of vodka and had threatened to jump off a freeway overpass on the 91 Freeway.

The man, in his late 40s, tells Tafoya he realizes he needs to stop drinking, and asks her how long he will be there.

She isn’t sure.

“If you follow up with (mental health subjects),” Tafoya says, “it dramatically reduces the chances of them being hospitalized again.”

Every day, the APD PERT checks on a backlog of clients they’ve contacted for follow-up. They try to do at least three to four follow-ups a day at homes and in hospitals.

Tonya Kruse, an RN at Anaheim Global, is happy to see the APD officers.

“These guys are so full of compassion,” Kruse says. “They’re amazing. If I had psychological issues, I’d want them to be in my corner. They are tender and gentle, but firm when they need to be firm.”

At around 1:30 p.m., a call comes in about a man threatening to jump onto the 57 Freeway from the Lincoln Avenue overpass.

Anaheim PD Officer Mathew Beck, left, and Officer Stephen Voss talk to a couple living in Maxwell Park about talking advantage of the offer of a shelter.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

By the time the PERT gets there, both sides of the freeway are completely shut down, with many motorists outside of their cars watching the drama unfold above – some yelling at the man to jump.

Tafoya gets the man’s name from an APD officer and runs it through the mental health system to see if he has a history.

Around 1:45 p.m., the man slips and falls feet first off the chain-link meshing above the overpass onto empty northbound lanes.

“Don’t look! Don’t look!” an APD officer yells at his colleagues.

The man survives.

Medics rush him to UCI Medical Center, where a doctor says he suffered a fractured pelvis and a fractured femur.

There, Tafoya writes a 5150 hold and hands it to a nurse. APD personnel remain with the man until one of the hospital’s four beds reserved for the mentally ill opens up so he can be transferred out of the trauma center.

By 3:15 p.m., members of PERT are at Maxwell Park, home to many homeless in Anaheim, to check on a couple who use meth and were staying in a shelter, but left to return to the park.

SUCCESS STORIES

The day before the ride-along, APD’s PERT, which is based out of the West Station on Beach Boulevard, had five calls, and wrote 5150 holds on three of them. The record, Beck says, is six 5150s in one 10-hour shift.

The team had planned to assist the FBI in assessing the mental health of a person of interest that day, but didn’t have time.

APD patrol officers use PERT, as do detectives and even dispatchers who deal with frequent callers with signs of mental illness.

“We dance a fine line between a patient’s medical information and getting police information,” Voss notes. “We’re really careful about the boundaries and how we exchange information.”

The PERT has had success stories.

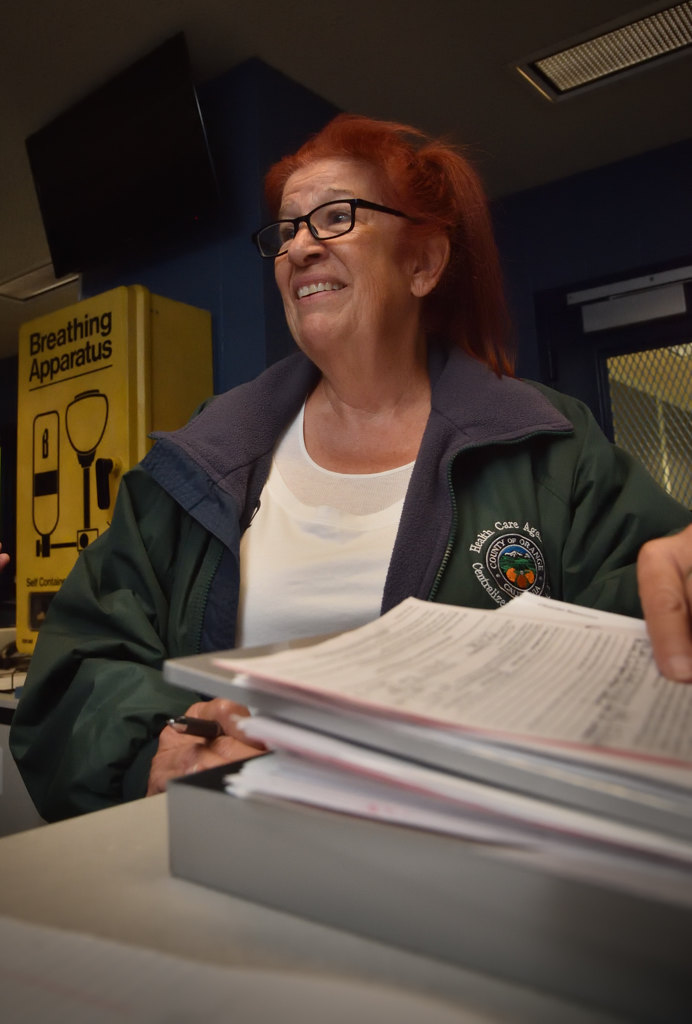

Mari Tafoya, a mental health specialist with the OC Health Care Agency and PERT member, visits the Anaheim PD jail to check on an inmate.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“The best thing that can happen to us is for someone to get placed on a mental health conservatorship, to get them housing and the 24/7 care they need,” Voss says. “Typically after that, we don’t see them for at least a year — or at all.”

A mental health conservator may be a relative, the Public Guardian’s Office, or a private professional conservator.

The APD’s PERT has sent one homeless woman to a hospital 17 times.

They are hoping to help secure a conservatorship for her, which requires the approval of a judge.

The team has gotten several homeless people off the street.

“One woman is housed in a room-and-board and lives off of Social Security,” Beck says. “She was a regular who we hospitalized a lot, and (the hospital) finally kept her long enough for her to get stabilized. Assisted outpatient treatment began, and heavy-duty case management got her housed. For several years, she was a regular fixture on Beach Boulevard, living on a bus bench.”

Tafoya says she learns something every day working on PERT.

“We stay very busy,” she says. “I have to say, the Anaheim PD does a great job.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge