Joseph Quezada was his family’s protector. Even at a young age, he never let barriers impede his inner call to help others, particularly his siblings.

His sister, Ashley, likes to tell a story that exemplifies her big brother’s heart.

Joseph, five years older, and his brother Michael would stack diapers against the side of Ashley’s play pen to help her climb out. Then Joseph would escape the pen and feed Ashley, making sure she was OK.

Years later, he would leave class to treat her to lunch at school if he hadn’t seen her recently.

Joseph Quezada kisses his son, Joseph Jr. (aka JoJo), who was five months old when his father died.

Photo provided by the Quezada family

He became like a dad to Ashley, now 22, a security blanket, even when at a young age himself.

Joseph came from difficult circumstances. His family tree is complicated. Including Ashley, he had 10 siblings, some of them half-siblings. He was adopted by Linda Quezada, a relative of his biological father. Joseph was a man loved by many. He was part jokester and guardian, competitive, but also nurturing.

“He lived a life of everyone,” Shannan Martinez, his son’s grandmother, puts it.

Ashley Quezada, sister of Joseph Quezada, who died in a car crash caused by a DUI driver, talks about her brother.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

That changed forever in November 2011. Dustin David Lish, a former La Habra High School classmate, rented a U-Haul truck from the La Habra facility where Lish worked. Lish had been drinking, prosecutors said, before arriving at the Lambert Road business with an accomplice.

He didn’t drive the truck at first, but eventually, Lish got behind the wheel. Prosecutors say he erratically veered the U-Haul into oncoming traffic, crashing head-on into the Hyundai Accent that Joseph had borrowed from his big brother.

Lish survived.

Joseph did not.

Following an exhaustive, detail-oriented case that lasted years, Lish, now 26, was sentenced in August 2018 to 15 years to life on a second-degree murder charge.

La Habra Police Sergeant Jim Tigner shows a photo on his phone to JoJo Quezada Jr., son of Joseph Quezada, 20, who was killed in a head-on collision with a DUI driver.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

That fall day, Joseph had planned to attend Ashley’s 16th birthday party and watch the TV game of his younger brother, Joshua, playing football for BYU.

Joseph Quezada was 20 years old. He left behind thousands who attended his funeral.

Among them was a son, Joseph Myles Jr.

JoJo, as he’s known, was five months old when his father died.

*

Linda Quezada adopted Joseph when he was 5. She says he was always an affectionate kid.

“He was the protector,” Linda says. “He was always the nurturing one.”

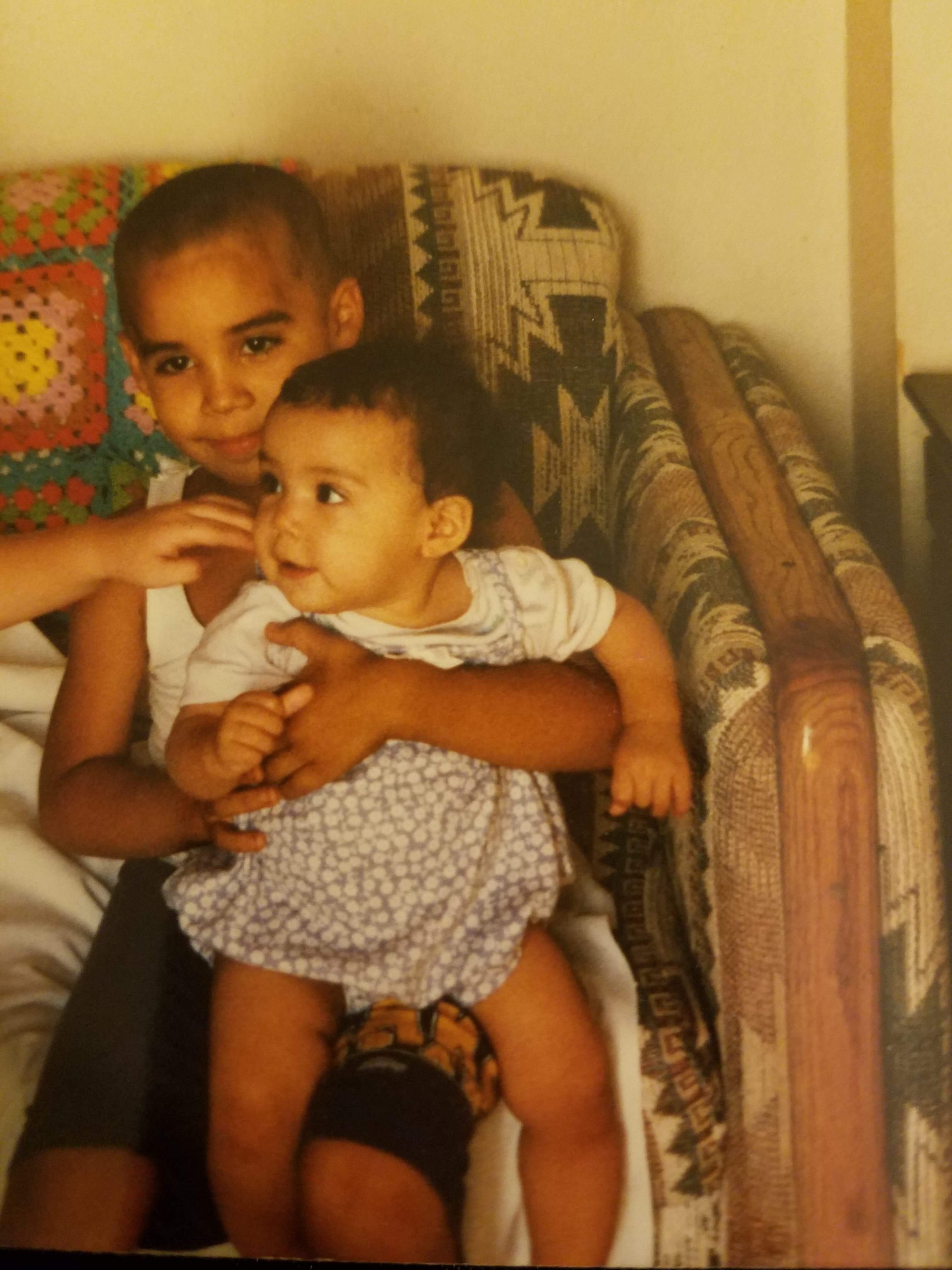

Joseph Quezada, pictured at around 6 years old, holds his little sister Ashley, then 2.

Photo provided by the Quezada family

One never expects such a caring nature from a boy, Linda says. But that’s how Joseph was.

When he was around 6, he got into flag football. Football became one of his life’s passions. He knew, even at that age, that he wanted to change his given last name, Flores, to Quezada and put the name on the back of his football jersey, much to Linda’s happiness.

Joseph played football for a few years at La Habra High, including a stint on the varsity team. He was always the life of the party, the light in the room. His eldest brother Jesse, 31, says Joseph loved many sports – including track, baseball and basketball – and was always athletic. Joseph, nurturing off the field, was anything but on it.

Jesse Quezada, left, brother of Joseph Quezada, with his mother, Linda Quezada, smile as they recall memories of Joseph.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

At 6-foot-1, he was heads above his competition. After high school, he got into rugby.

His love of sports extended to coaching children’s teams. After JoJo was born, Joseph brought his infant son to the football field aboard a Babybjörn.

“Anything that had to do with kids, he was all about,” Jesse says.

The family of Joseph Quezada, who was killed at age 20 in a head-on collision in 2011 in La Habra. From left, back row: Shannan Martinez, Joey Martinez Jr., Joey Martinez Sr. From left, front row: Ashley Quezada, JoJo Quezada, Heather Martinez, and Alexis Martinez.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

Rugby was a sport he could call his own, Jesse says, because none of his siblings played it. Years after his death, Joseph’s Fullerton rugby crowd still visits JoJo at Christmas, Easter and other events.

The first and only rugby game Linda attended, Joseph blew out his knee. The ambulance came to take him away, and Linda scolded him.

“Didn’t I tell you?” she said. “I don’t want you to play this!”

*

The Quezada family was known in the La Habra football world for their athletic prowess, but Heather Martinez didn’t know that. Nor was she impressed.

“I guess I missed the boat,” she jokes.

JoJo Quezada Jr. and his mother, Heather Martinez. JoJo’s father and Heather’s boyfriend, Joseph Quezada, was killed by a DUI driver in November 2011.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

Heather caught Joseph’s eye one day circa 2007, when he went to visit Ashley at cheerleading practice. Heather was Ashley’s coach.

When Heather saw Joseph, she couldn’t help but laugh. His outfit reminded her of a Hot Dog on a Stick uniform.

It was a sunny day. Joseph accompanied Heather to 7-Eleven for Slurpees. As the oldest in the group, Heather drove, and Joseph called shotgun for the chance to sit next to her. At 7-Eleven, Joseph poured every flavor into his Slurpee cup – that was his favorite.

An estimated 2,000 people attended the funeral services of Joseph Quezada in 2011.

Photo provided by the Quezada family

Later that day they went to a baseball game, where Joseph gave Heather his number.

“He’s super confident, but I didn’t even look at him like that at all,” she recalls. “You work at Hot Dog on a Stick? I don’t know.”

In the subsequent months, Joseph asked Heather out repeatedly, failing “probably a hundred times,” by her count. Joseph learned where Heather hung out, and he put himself there too.

One time, Joseph left a note on her car. He signed it, “Friend.”

La Habra Police Officer Amsony Mondragon checks drivers during the La Habra Police Department’s Labor Day weekend DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road in La Habra. The checkpoint was held in memory of Joseph Quezada, who was killed by a DUI driver in 2011. Quezada’s car was on display on a flatbed truck for drivers to see.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

“I was not playing hard to get,” Heather admits. “I was just not interested.”

Eventually Heather changed her mind. During a movie date to see “Employee of the Month”, Joseph kept repeating her name until, by the end, he asked her to be his girlfriend.

Heather obliged.

*

Joseph faced adversity throughout his life, but never lacked people who cared for him.

Joey and Shannan Martinez, Heather’s parents, took him under their wing when they lived in Chino and La Habra. He joined them on trips to the Colorado River and Lake Havasu, doing things he had never done before.

“He was a son to us, too,” Shannan says.

The La Habra Police Department held a Labor Day weekend DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road in La Habra in memory of Joseph Quezada, who died following a DUI-related collision at age 20 in 2011.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

“He had a beautiful spirit,” Joey adds. “He was a very family person. He just had an aura about him. You could see it, as a coach, as a father. I could see something in him. He was good, genuine.”

Joseph and Heather produced a child, and they had to break the news to Joey and Shannan. Heather was nervous, unsure how her father would take it.

Heather remembers him looking down, taking a minute, then looking up.

“So,” he said, “football in five years?”

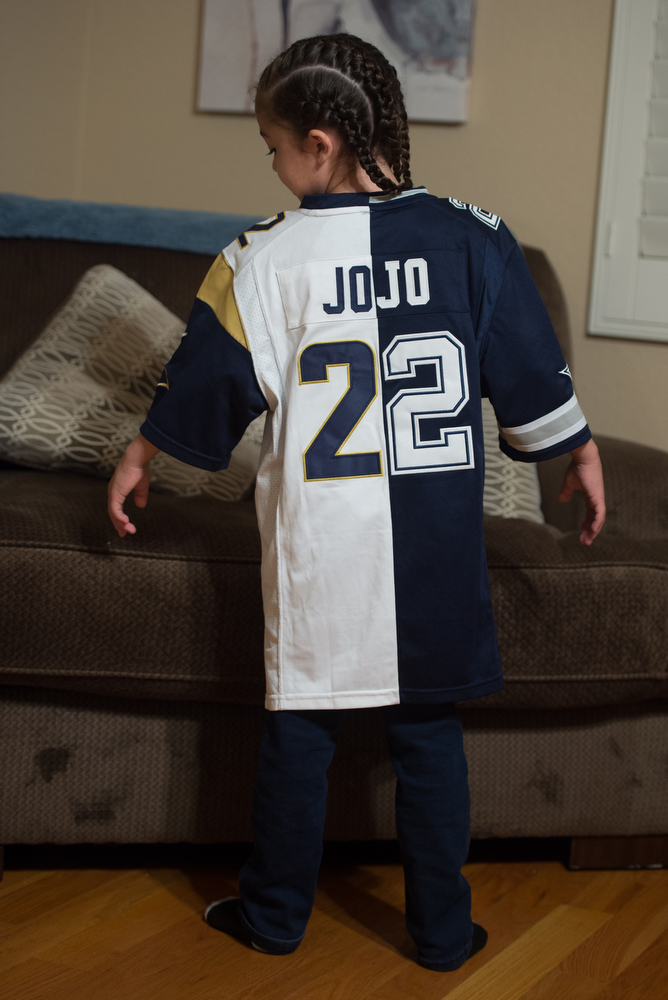

JoJo Quezada Jr. shows off his Rams-Cowboys jersey. JoJo is the son of Joseph Quezada, 20, who was killed in a head on-collision by a DUI driver in 2011.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

Heather and Joseph named their baby Joseph Myles, after his father.

Heather endured a difficult pregnancy. She was hospitalized for three days.

Jesse, Joseph’s oldest brother and JoJo’s godfather, describes JoJo’s birth as the happiest day of Joseph’s life, even though the labor made him anxious.

JoJo was born on Father’s Day, June 19, 2011. Joseph was scared to cut the umbilical cord.

“This is your Father’s Day gift,” Heather told him.

Joseph cried, “like a baby,” his family recalls. He wasn’t prone to doing that.

La Habra Police Department held a Labor Day weekend DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road in La Habra.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

Joseph showed JoJo off to his friends. He knew how to take care of an infant to a degree that even surprised the nurses.

Formula, ice pack, diaper bag – check, check, check.

“He was no rookie,” Joey says. “He knew what to do.”

*

The day of the crash, first responders cordoned off the site.

Shannan Martinez and Ashley Quezada happened to drive by the scene. While sitting at a long red light, their hearts sank. Somehow they felt connected to whatever had happened. Ashley surmised that it must’ve been a devastating accident.

“We have to pray for whoever’s there,” she told Shannan.

The family was celebrating Ashley’s 16th birthday and watching Joshua play football on TV for BYU.

Joseph wasn’t answering his phone.

The game ended.

Still no Joseph.

La Habra Police Sergeant Jim Tigner, right, talks with the family of Joseph Quezada, who was killed in a head-on collision with a DUI driver in November 2011. The La Habra Police Department held a DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road in La Habra in memory of Quezada.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

That night, the police came to the Quezada home to deliver the horrible news. Jesse’s anger turned to shock at the realization that his brother was dead. He knew that as the oldest, everyone would be looking to him for guidance.

“I had about one minute to get through my own thoughts with what’s going on,” he said. “It’s almost like a nightmare, a dream. This isn’t true. It was like that for a few days.”

That night, Jesse visited the crash site looking for answers. Jesse contacted Joshua and his brother Joe at Montana State, telling them to fly home and avoid social media. Jesse wanted to tell them in person.

The Quezada siblings had a way of organizing themselves in pairs. Each had a partner who was closest to the other in age. For Joseph, a Cowboys fan, his was Joshua.

Ashley Quezada, sister of Joseph Quezada, talks about her brother, who was killed in a collision with a DUI driver in La Habra in 2011.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

The two exchanged text messages when Joshua played football at AT&T Stadium, the Cowboys’ home turf. He noted to Joseph how something they dreamed of as kids was coming true.

Before Joseph’s death, Jesse envisioned Joseph and Joshua playing football together at Fresno State, where Joshua eventually transferred. Joseph was talented enough that he could’ve walked on the team, Jesse figured.

“I thought that would be a perfect situation, being back with his brother,” Jesse says.

Linda was in Riverside when she heard the news.

“It was like being in a tunnel. It was numb,” she says. “It was like I didn’t hear what they said, but I heard what they said. It didn’t make sense. It couldn’t make sense.”

Linda questioned everything. She knew the family was in for a long trial.

*

Lish’s family struggled as well with what he had done. One time, Lish’s mother approached Linda at a Walmart, telling her their prayers were with the Quezada family. Linda thanked her for the kind words, but didn’t realize until later who the woman was.

Linda Quezada smiles as she reflects on the good memories of her son, Joseph Quezada.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Joseph was buried at Rose Hills Memorial Park and Mortuary in Whittier. An estimated 2,000 people attended Joseph’s funeral, folks he knew from school, his family, sports, friends he rode with as well as members of the youth football team he coached.

A memorial of candles was set up at the crash site immediately after the incident. Memorials have appeared there in the years since. Joseph’s name is memorialized on a bench in Estelli Park in La Habra that was organized by his godmother, Freda Padilla.

Strange forces have been at play since Joseph’s death, the family says.

When JoJo was 2, Heather took him to the intersection where Joseph was hit. Suddenly, JoJo pointed to the exact crash site and said aloud, “Da Da!”

Heather was shocked. She hadn’t told JoJo about the site, or its significance.

“He had no idea,” she says.

Alexis Martinez, Heather’s sister, has overheard JoJo in his crib by himself, laughing and giggling as if somewhere were there. Was it Joseph?

JoJo Myles Quezada, Joseph Quezada’s son, visits the memorial site in La Habra where his father was killed in a DUI incident in 2011.

Photo provided by the Quezada family

Joseph’s family is constantly reminded of him through JoJo: his athleticism, outgoing nature, competitive streak and even physical attributes like his eyebrows, ears and hands.

And, of course, they see Joseph’s nurturing nature.

“I see a lot of the protective side in JoJo,” Heather says.

The Quezada family gets together on the anniversary of Joseph’s death. Linda says she hopes the annual outings make the day go by faster, helping everyone avoid dwelling on painful memories.

They have been to theme parks. One year, 22 of them boarded a cruise that Linda had been planning since before Joseph’s death. Instead, they held the trip in honor of Joseph. When Linda saw all the kids interacting together she thought, “I couldn’t ask for anything else.”

*

The demolished Hyundai Accent that Joseph was driving was donated to the La Habra Police Department.

On a recent Friday night, not long after Lish’s sentencing, the department held a DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of Lambert Road, near where Joseph’s car was hit and in front of the U-Haul store where Lish acquired the truck. Cpl. Nick Baclit, one of the first responders to the 2011 crash, was there to screen drivers. In total, 11 sworn officers, six civilian staff and about 20 Police Explorers worked the evening.

La Habra Police Sergeant Jim Tigner holds a meeting with fellow officers at the La Habra Police Department before a Labor Day weekend DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road, in memory of Joseph Quezada, 20, whose car was hit in a head-on collision with a DUI driver.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

Given the conviction and knowledge that Lish was poised to serve time in prison, La Habra police made the state grant-funded DUI checkpoint notably symbolic.

Under the guidance of Motor Sgt. Jim Tigner of the department’s traffic bureau, nearly everything about the effort held a deeper meaning: its timing in conjunction with Lish’s sentencing, where the checkpoint took place, who came to watch and even the staff there.

The first thing drivers saw was an electronic sign indicating that the screening was in memory of Joseph Quezada. Behind the sign was the Accent, resting on a tow bed, illuminated by floodlights.

Members of Joseph’s family came to watch the patrol, including Ashley, brother Michael Rangel, and JoJo, now 7. This was the first time some of them had seen the car.

Life has been difficult after her brother’s death, Ashley says, but his life hasn’t been in vain.

La Habra Police Department holds a DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

The tragedy of his loss is “being talked about every day,” Ashley says, and its takeaway message is painfully clear: “Don’t drink and drive. You can destroy souls.”

For Tigner, Quezada’s death stood out from others in his long career. For one, it involved a well-known La Habra family. For another, it involved one classmate killing another under the influence of alcohol.

Tigner said the department uses checkpoints as a deterrent against drunk driving, or, in the words of La Habra’s high-visibility enforcement campaign, “Drive sober or get pulled over.”

The checkpoint had 578 vehicles pass through. Among the results were one arrested driver suspected of being under the influence of marijuana and others driving without a license.

The La Habra Police Department holds a DUI checkpoint in the 700 block of East Lambert Road.

Photo by Stephen Carr/Behind the Badge

Tigner says the checkpoint wasn’t necessarily about catching impaired drivers. If there were few or none of them, that would be good, as it would indicate that fewer impaired people are behind the wheel and the city is safer.

“Our goal is really about DUI education and deterrence,” Tigner says. “Driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs is so preventable.”

Tigner never refers to cases like Lish’s as “an accident.”

“It was a series of bad choices,” he clarifies. “It wasn’t an accident.”

Joseph’s family says they are thankful for the Herculean effort behind Joseph’s case.

“We can’t thank everyone who was a part of it enough. It was a team effort,” Jesse says. “We are forever in their debt.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge