When he first joined the Anaheim PD’s Traffic Unit as an investigator in 2016, Doug Elms decided to take his new colleagues, Investigators Rick Alexander and Gonzalo Perez, to lunch.

No sooner had the group sat down with their menus when their phones went off.

A motorist driving nearly 100 mph down Harbor Boulevard had spun out of control and rammed into the front of an OCTA bus.

His car had gone into a centrifugal skid, and he was impaled by prongs on the bike rack on the front of the bus. Several of the 15 or so passengers inside the bus suffered mild to moderate injuries.

Elms and his colleagues had to immediately drop everything and roll to the scene to figure out the dynamics of the collision, such as studying fresh skid marks to estimate the car’s speed, and looking for other clues that would give them as clear a picture as possible of what happened.

That’s the way things go for the APD’s Traffic Unit: A call can come in at any time.

The three members of Anaheim PD’s Traffic Investigation Unit are (from left) Officer Rick Alexander, Officer Gonzalo Perez and Officer Doug Elms.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

And, as the investigators piece together reports that can take months before being forwarded to the O.C. District Attorney’s Office for possible prosecution, lives hang in the balance – say, a driver suspected of vehicular manslaughter.

It’s meticulous and, at the scene of accidents, physically demanding work, with investigators spending a lot of time on their knees scouring what’s known in the trade as the RP (resting position) of the cars involved and analyzing the debris field.

Think of their work as kind of like rewinding a movie after it ends to figure out what happened before.

And, recently, their work – as well as that of APD Forensic Specialist Mark Currier — led to the identification of a suspected villain of a fatal hit-and-run. And all they had to work with, initially, was a small piece of a shattered headlight lens.

SKILL, COMMON SENSE, LUCK

Officers who join the traffic unit often become lifers.

That’s certainly the case with Alexander, a 33-year veteran of the APD (which makes him its most senior sworn employee) and a member of the traffic unit since 1991.

Like Perez and Elms, Alexander loves the investigative part of his work.

“It’s like putting a puzzle back together,” Alexander says.

Perez, an APD officer since 1994, has been investigating traffic collisions since 2007.

Elms joined the APD in 1990 and left for three years to be a federal air marshal after the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. He was a motor officer for 11 years before becoming a traffic investigator in 2016.

With Alexander and Elms planning to retire in 2019, Perez will become the grizzled veteran on the APD traffic investigation unit, with two newbies expected to join him (the plan, hopefully, is to get a fourth investigator).

The unit’s caseload is large, and cases come nonstop.

On Mondays, Perez and Elms usually are chained to their desks after the inevitably busy weekends.

Anaheim PD Traffic Investigators Rick Alexander and Doug Elms talk about their work in their office at police headquarters.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“If any (driver) is in custody, that’s a priority,” Perez explains of working cases. “Then we move onto reports that have to be submitted, and we return calls that came in over the weekend.”

The state mandates, in excruciating detail, how collision reports need to be filled out, and patrol officers typically don’t do them often enough to master them. So the traffic investigators usually have to fill in holes on collision reports.

“There are patrol officers who would rather take a rape report or a murder report than a traffic report,” Alexander says. “They’re just more comfortable doing that stuff.”

The three of them review and approve all traffic collision reports that come through the agency, from fender-benders to fatal collisions. That totals between 7,000 and 8,000 reports per year.

The three conduct follow-up investigations on hit-and-runs, issue citations, and work with the district attorney’s office and the city attorney’s office on any work requests, such as following up on a victim’s injuries, or doing background checks on drivers.

Between the three of them, they currently have about 250 open hit-and-run cases with workable information – “workable information,” nine times out of 10, meaning a full or partial license plate.

License plates fall off all the time or leave imprints on other vehicles.

“We’re slammed,” says Alexander, who along with Elms and Perez is on call 24/7.

Perez and Elms regularly work from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Thursday; Alexander regularly works the same hours Tuesday through Friday.

KEY SKILLS

Algebra, trigonometry and physics are essential skills for traffic investigators.

“We have very good computer programs (one named Crash Zone) to aid in the analysis,” Alexander says.

Perez took drafting classes in high school and college.

“Sometime things come full circle,” he says. “I was really good at math. I put that aside when I became a police officer. When I came to traffic, I did diagrams and math equations to solve certain momentum analyses and reconstruction. I realized, ‘Wait, this is up my alley with what I used to do in the past.’ So I stayed on the unit.”

When the three arrive at the scene of a traffic collision, they need to be able to look and have an idea of what happened.

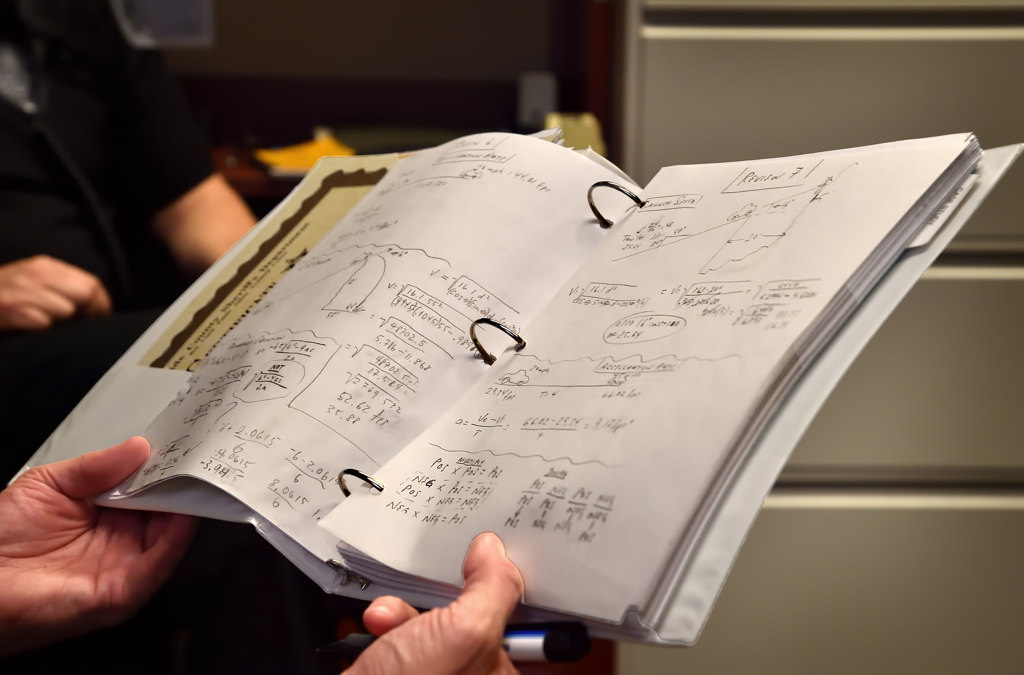

A notebook shows algebraic equations used to determine speed and angels of a traffic collision scene.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“So you see a car here and skid marks over there,” Alexander explains. “You have to be able to say, ‘Well, damage on this car is on this side, so it was going in this direction.’ We have to be able to step back and sort of visualize what happened.”

To diagram an accident, the team uses Total Station, a surveying tool that measures angles between designated visible points in the horizontal and vertical planes. Another way they take measurements is the triangulation method, in which two fixed items such as streetlights are used to take measurements.

To get the measurements perfect, the investigators align their diagrams up with satellite images of the scene.

Common sense, too, has a lot to do with their work.

And, sometimes, luck.

Both came into play on the evening of Nov. 24, 2018, when APD officers responded to a call of a woman lying in the roadway on Haster Street, near East Leatrice Lane, just before 9 p.m.

The woman, later identified as 18-year-old Jacqueline Diaz-Lara, was suffering from major injuries and appeared to have been struck by a vehicle.

Diaz-Lara had been hit while walking home from her job at Buca di Beppo Italian restaurant on Harbor Boulevard in Garden Grove.

Alexander, Perez, and Elms spent 2 ½ hours scouring the scene for clues. Currier found a 3 1/2 –by-4 inch piece of a headlight lens in the debris field.

Luckily, the headlamp had shattered in just the right way that the part number was readable.

Anaheim PD Investigator Rick Alexander gets on a knee to get a closer look at the scene of a fatal hit-and-run on Nov. 24, 2018.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Three days after the collision, Diaz-Lara died at UCI Medical Center.

By then, APD investigators had been able to determine the shattered headlight lens had come from one of three vehicles built in 1998 or 1999: an Izusu Rodeo, Isuzu Amigo, or a Honda Passport.

They narrowed it down further. Because investigators also found orange paint chips linked to the suspect’s car, they ruled out the car being an orange Passport, since Honda doesn’t make that model in that color.

Perez accessed a database and found two cars registered to Anaheim residents that possibly could be the suspect’s car.

One of them, an Isuzu Rodeo, was registered to Osvaldo Soto-Juarez, 20. Investigators located his car, which not only matched the description of the suspect’s car, but also was missing the recovered piece of headlight lens.

Five days after the fatal hit-and-run, Soto-Juarez was arrested without incident.

FATALITIES DOWN

In 2017, there were 22 fatal traffic collisions in Anaheim. The average is 18 to 20 per year.

With 2018 almost in the books, there only have been 10 fatal traffic collisions in Anaheim this year, six of them involving pedestrians such as Diaz-Lara.

Anaheim PD Investigators Gonzalo Perez (left, with tripod) and Rick Alexander survey the scene of a fatal hit-and-run at Haster Street near East Leatrice Lane on Nov. 24, 2018.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

The three investigators believe the APD, through social media and other means, including community outreach, has been doing a stellar job educating the public about pedestrian and motorist safety.

But pedestrians, as well as motorists, never can be reminded enough about how important it is to walk and drive as safely as possible.

Sadly, speed remains a common factor in road fatalities.

Perez pulls up a video on his computer. It’s footage of a female motorcyclist who filmed her own death.

The woman, a GoPro camera attached to her helmet, was speeding down La Palma Avenue, nearly going 100 miles per hour, when a car coming from the opposite direction pulled in front of her to make a left turn.

The woman’s last words can be heard on the video:

“Oh God! Oh God!”

Elms, Perez, and Alexander have seen a lot of carnage.

“When we’re in the field,” Alexander says, “we’re so busy we don’t dwell on it. We have to be able to function when we’re doing our job.”

Alexander says his hardest case was a double fatality fifteen years ago outside Centralia Elementary School on north Western Avenue. The victims, two little girls who were sisters, were the same age as his daughters.

A lot of pedestrians die because they assume they have the right of way when they walk out onto streets, the investigators say.

Asked the most important thing he’s learned over the years when it comes to preventing motorcycle and bicycle fatalities, Alexander has a quick answer:

“Wear a helmet.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge