As an original member of the Community First Conference planning committee, recently retired Westminster Police Department Commander Mike Chapman helped develop the principles and standards that have been used to plan the event every year since.

Chapman was recognized for his contributions at the 15th Annual Community First Conference, held Oct. 16 at the Delta Hotel in Garden Grove.

Hosted by College Hospitals and the Orange County Health Care Agency, the conference joins law enforcement with mental health professionals in order to network and discuss the trauma that engulfs survivors and first responders in the wake of mass shootings.

Westminster PD Commander Michael Chapman after asking his wife, Mindy, to join him on stage as he is honored for his years of service and his work with the Community First Conference.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“Mike has been a rock for this conference,” said Anaheim Police Lt. Dan Friesen, the conference moderator. “Throughout the years, he has remained a constructive and creative influence in the planning of these conferences.”

In 2013, Chapman was instrumental in developing a ride-along program, where police officers would partner with mental health professionals in order to help homeless and mentally ill members of the community.

The retired commander also has received awards from the Orange County Human Relations Commission and the Chamber of Commerce for his work establishing the protocol of how the department assists that population.

Las Vegas Metro Police Sgt. Jerry MacDonald (retired) talks about the Las Vegas Route 91 Music Festival mass shooting before playing an audio timeline with radio calls during his speech at the Community First Conference.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

This year’s Community First Conference centered around lessons learned and the traumatic impact felt in the wake of the mass shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, 2017.

The shooting, which took place on the final day of the three-day country festival, remains the worst mass shooting in U.S. history, with 58 people killed and hundreds more injured.

Previous years’ topics have included the San Bernardino mass shooting, the Virginia Tech shooting, and the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, all of which resulted in multiple casualties and deep emotional scars.

Retired Las Vegas Metro Police Sgt. Jerry MacDonald talks about his department’s response during the Las Vegas Route 91 Music Festival mass shooting.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“I’ve been in law enforcement for 20 years,” said an Orange County Sheriff’s Department investigator who was attending the concert with his wife and friends.

The investigator, whose name is being withheld because he works undercover, was a keynote speaker at the conference.

Heather Williams (left), one of the speakers during the Community First Conference, gives Autumn Bignami, a teacher at Paramount High School who was wounded during the Las Vegas shootings, a hug after asking Bignami to come up and give her first hand account of what happened.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“Of all the calls I’ve responded to, of all the education and training I’ve been to, nothing prepared me for what occurred at Route 91 that day,” the investigator said.

The investigator, who was attending the event with family and friends for the second year in a row, was seated to the left of the stage, in between the crowd and the Mandalay Bay and Luxor hotels on the other side of Las Vegas Boulevard.

Everything was going well, he recalled.

Autumn Bignami, a teacher at Paramount High School who was shot during the Las Vegas Route 91 Music Festival mass shooting, suffering significant and permanent injures, talks about what she and her husband, who was also wounded, went through.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“All of a sudden out in this distance we heard a sound,” said the investigator, recounting the beginning of what became the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history. “Then we heard some more sounds. This time the sounds were a lot louder and a lot more defined. We realized something is going on. Something is wrong.”

The OCSD investigator was among 40 sworn and unsworn members of the OCSD, along with dozens of public safety professionals, including many from Orange County, who were in Las Vegas attending the concert.

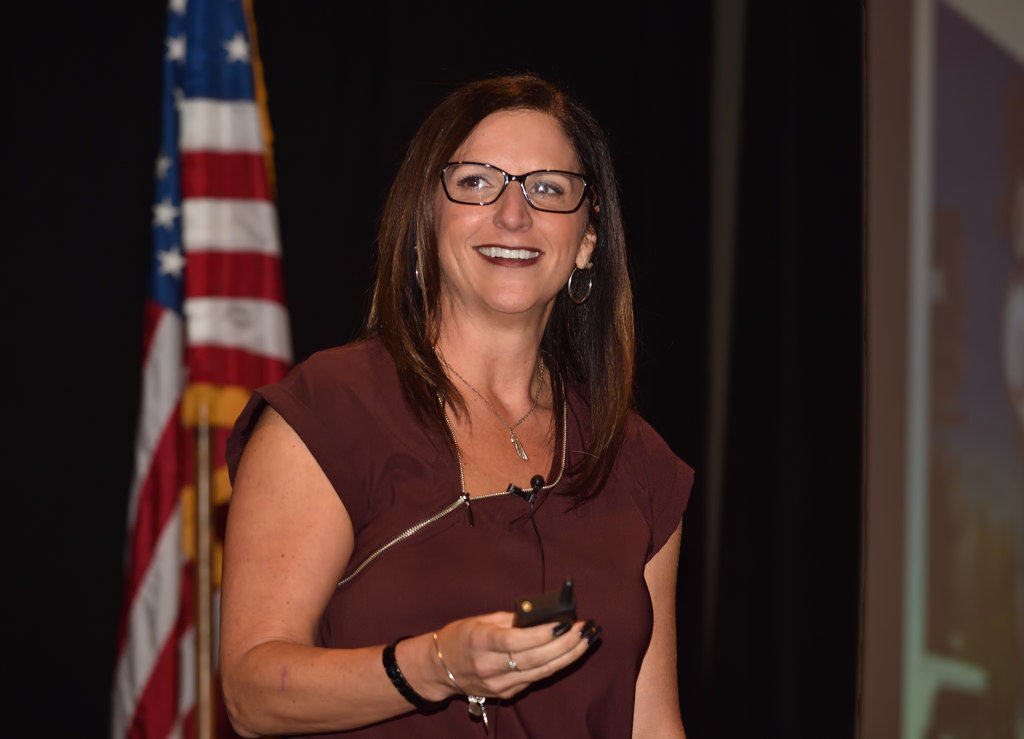

Heather Williams, who has a doctorate in psychology, talks about the response and recovery in the aftermath of an active shooter to a crowd of law enforcement, fire, hospital, and other first responder personnel during the Community First Conference.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

When the shooting occurred, police officers and firefighters switched to first-responder mode.

“You could hear the bullets as they are hitting the metal bleachers and hitting the ground all around us,” the investigator said. “And you wonder, ‘What do I do next? Where do I go from here?’ Because there is no safe spot. Everything was completely open.”

Ultimately, he took charge, leading a group of concertgoers to safety.

But more than two years later, trauma still lingers.

Heather Williams smiles before the start of her talk on what first responders go through in the aftermath of an active shooter incident.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“We still struggle going to concerts,” the investigator said. “We still struggle going to events. It’s a constant effort to continue to improve.”

The investigator did not sustain physical injuries at the Las Vegas shooting, but Sgt. Brad Powers of the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department wasn’t as fortunate.

Powers, who also shared his Route 91 experience at the Community First Conference, was situated in a VIP area to the left of the stage when the shots rang out.

Conference moderator Anaheim PD Lt. Craig Friesen introduces each speaker at the Community First Conference.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“The noises that were coming and raining down were pretty horrific,” Powers said.

He suddenly realized he’d been shot in the groin.

Powers was taken by a Good Samaritan in a pickup truck to Sunrise Hospital where he flatlined twice during surgery.

San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department Sgt. Brad Powers talks about his experience as a victim of the Las Vegas shooting, and how it affected his life afterward, at the Community First Conference.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

He spent three weeks at Sunrise Hospital before being admitted to Loma Linda University Medical Center, where he spent months rehabbing.

Initially, Powers declined numerous invitations for counseling.

“Some time goes by and (I) realize I’m not walking so good,” he said. “I have no strength. I started withdrawing more and more.”

Anaheim PD Officer Kenneth Florendo (center) was among those in attendance at the conference.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Powers slipped into such a deep depression he was unable to work and then came up with what he believed to be a permanent solution.

He pulled a gun out of the safe in his house, walked outside, and was on the verge of pulling the trigger.

The police were called and convinced Powers to put down the gun.

Finally, he agreed to get help.

Conference moderator Anaheim PD Lt. Craig Friesen with Community First Conference speakers Autumn Bignami (center) and Heather Williams.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“We can’t push (our feelings) down,” Powers said. “It doesn’t work. I was messed up. I was at my lowest point. It took my almost killing myself to realize how bad I needed help. I’m here today because I got help. If you have a friend who you see going through stuff, don’t push him aside. Sit down with him and get him help.”

The OCSD investigator said he has found healing from speaking in public about the shooting, where he is able to express his feelings.

He also expressed gratitude toward the peer support available in his agency and from Heather Williams, Regional Peer Support Coordinator for the OCSD.

“From the very first step, she’s been there for us,” he said.

Williams, who also was a keynote speaker, oversees a team of nearly 100 OCSD personnel, provides crisis counseling, and coordinates an emotional wellness campaign.

Community First Conference speakers Autumn Bignami, left, with Heather Williams.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Williams was getting calls back in Orange County within hours of the shooting.

Her staff began to compile a list of all the OCSD employees who were there.

She also was getting calls from other agencies looking for help.

Williams coordinated a streamlined system to get law enforcement personnel into therapy.

The Las Vegas shooting was particularly difficult because her crisis team was responding to colleagues in law enforcement.

“It was a very unique dynamic and something I hold very close to my heart based on the situation and types of reactions we had to work through,” Williams said. “It became very clear that this impact was going to be far reaching, not only within our department but across Orange County and Southern California law enforcement and fire agencies.”

Victims of trauma often want their lives to return to normal, Williams said, but that’s not possible.

Instead, survivors need to find “a new normal,” she said.

“It becomes stressful because it’s about change and transition and a lot of people don’t like it,” Williams said, “but I can tell you that on the other side of this new normal is that people grow and the resiliency, which is the ability to adapt and overcome, is absolutely amazing.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge