Tustin police waited more than 20 years and traveled nearly 900 miles for this.

Then-detective Ryan Coe and Reserve Det. Bruce Williams knocked on the door of the Oregon residence and announced their arrival.

The elderly man on the other side of the door had receding cotton-like hair, beady eyes and a drawn mouth.

He didn’t protest.

In fact, he didn’t even speak.

Charles Clark, 78, simply turned around and put his hands behind his back.

“It was that easy,” Williams said. “He knew that one day, he was going to be caught.”

In two decades of navigating a tale of crime, murder and unlikely love, Tustin police finally had their man.

The frustrating part: They knew it had been him all along.

Tustin Reserve Det. Bruce Williams escorts Charles Lee Clark from Oregon. Clark was arrested in 2013 for the 1990 murder of Kathleen Witkowski. Photo courtesy Tustin PD.

***

Clark’s FBI criminal history spans 21 pages and dates back to 1989 when he stabbed a Marine in the chest with a buck knife during a bar fight.

The incident underscored an undeniable flaw in Clark’s personality that his two wives later would attest to:

He had anger issues.

Police would also discover Clark had obey-the-law issues.

Clark was convicted in November 1990 by a federal judge for robbing three banks in Orange and Los Angeles counties. He used a note to coerce tellers to hand over the loot, police said.

After his conviction, Clark wasn’t taken into custody, Coe said.

“He was always complaining about heart issues,” he said. “They allowed him to stay out to get treatment.”

Clark was due back in court in January 1991 for sentencing.

Shortly after his conviction, Clark met Kathleen Whitney Witkowski — a 38-year-old waitress her family described as friendly and witty.

Witkowski was beautiful, by any standard, and was vulnerable when she met Clark, who was 52 at the time, her family said.

Some said they were in love, although Witkowski only ever introduced Clark as her friend.

The two lived together in an apartment complex near McFadden Avenue and Newport Avenue, Coe said.

They knew each other for less than two weeks before moving in together.

Some speculate Clark was hoping Witkowski would be the Bonnie to his Clyde, but with a better ending to their tale.

But when Clark used her 1977 black Pontiac Grand Prix to rob a Tustin bank, Witkowski protested.

They argued, and loudly. The neighbors heard the fighting, Coe said.

That day — Nov. 15, 1990 — was the last anyone heard from the beautiful waitress.

“I believe very much it was her resistance to a life of crime that Charles Clark wanted and she said, ‘No, I’ve had enough,’’’ Williams said.

***

On Nov. 20, 1990 the property manager of the complex noticed Witkowski’s door ajar.

She called into the apartment, but there was no answer so she yanked the door closed.

Three days later, neighbors reported an odor emanating from Witkowski’s apartment.

Police were called and they found the oven on at 400 degrees with two charred potatoes inside.

The smoke alarm had been ripped off the wall.

In a back room, among moving boxes and clothes, Witkowski’s body was found on the floor.

She had been stabbed to death — a gash in the center of her chest later determined to have been the fatal wound.

Police concluded she died on Nov. 18, 1990.

“We speculate that whoever did this maybe wanted the apartment to catch fire and didn’t want the smoke alarm to go off and alert anybody,” Coe said.

When police went to look for her Grand Prix, it was missing.

***

A harried and bearded Charles Clark arrived in a black Grand Prix in Las Vegas in November 1990.

Clark spent a lot of time in the desert. He was a hang gliding enthusiast and he claims to have invented the Ultralight aircraft (although a quick search of the history of the Ultralight contradicts his claims).

There he visited his friend, Bill Hallam.

Clark showed up with a deep cut stretching from his right hand to his right wrist. He told Hallam he could not return to California.

Clark shaved his beard and then told Hallam they needed to burn the Grand Prix, Coe said.

Hallam grew suspicious and later called the FBI.

A hit came back on the vehicle: The driver was wanted for questioning in a homicide in Tustin.

Hallam would be integral in building the case against Clark.

That was until he reportedly jumped from a plane and his parachute didn’t open.

The original detectives never were able to build a case that could be prosecuted.

Without Hallam, the evidence was too circumstantial.

Clark started his 33-month sentence for bank robbery in January 1991 and although detectives questioned him about the Witkowski murder before he served his time, Clark’s only response was: “I’m not telling you anything,” Coe said.

***

Coe said Tustin was a different place in the 1990s. Detectives navigated hefty caseloads and forensic technology was not as advanced as it is today.

With Clark serving time in federal prison for robbery, detectives put their focus on cases that needed immediate attention, with suspects who were not already behind bars and with evidence that would hold up in court.

But the Witkowski case never was forgotten.

Fresh eyes on a case or advancements in technology might take a case from unsolved to closed, so it’s important to routinely review cold cases, police said.

Williams remembered the Witkowski case — as the Tustin PD’s resident cold-case detective, it came across his desk once before about a decade ago.

“It was a case I was comfortable that we knew who the suspect was,” he said. “We knew it when it happened.

“It was frustrating. Sometimes we know who the suspects are and are just not able to get our hands on them.”

In 2013, it was time to review the case again, so Williams started his work the way he always does: by pinning a picture of the victim in his cubicle and saying a prayer.

“I always pray over my cases,” he said.

This time, Williams would partner with Coe — who had served as a detective for about a year.

Williams said Coe was tenacious and smart. The two pored over every minute detail of the case.

They reviewed folders full of information and re-submitted DNA evidence to the Crime Lab.

Multiple DNA hits came back that strengthened Tustin’s case, but they needed more.

Then Coe found the report that described Hallam’s supposed death — the skydiving jump gone wrong.

Coe kept thumbing through the file and noticed there was no death certificate.

“I said to Bruce, ‘Are we sure this guy is dead? Let’s run his name again,’” Coe said. “Sure enough, he was alive and well and living in Las Vegas.”

When Coe and Williams arrived at Hallam’s home, Hallam told them: “I’ve been waiting for you guys to talk to me.”

The two cops wondered if Hallam could recall the events accurately.

Hallam was sure he could help.

“You don’t forget something like that in life,” he told them.

***

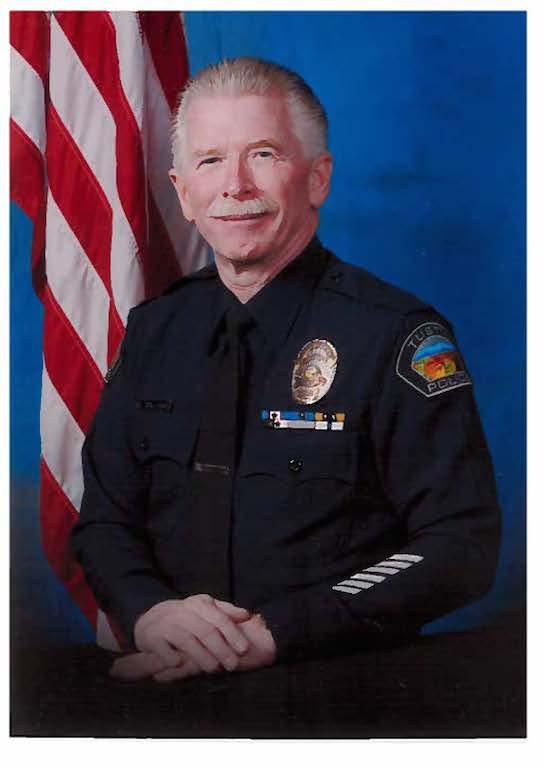

Sgt. Ryan Coe of the Tustin PD who, with the help of many others at the department, recently solved the 1990 cold case murder of Kathleen Witkowski resulting in a confession and conviction of Charles Lee Clark.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

After Williams and Coe arrested Clark in August 2013 in Beavercreek, Ore., Clark was haughty and somewhat aloof.

He sipped on a bottle of root beer over a meal at the airport telling the detectives, “I’ll be out in two weeks.”

But with new DNA evidence and a key witness ready to testify, Clark instead ended up taking a deal from the Orange County District Attorney’s Office.

In January, he pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to 11 years in state prison.

“With the hard work, time and energy that you, and the detectives before you, put in it is certainly rewarding,” said Coe, now a sergeant. “The most rewarding part was being able to call (Witkowski’s) sister and give her closure on the case.”

After the case was closed, Williams pulled the pin from the black-and-white photo of Witkowski that stared over him every day and filed it away.

The detectives, too, found closure.

“I have a lot of respect for her,” Williams said. “She didn’t deserve what she got.

“I can tell you clearly that this was an answer to my prayers.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge