Sore back.

The 39-year-old woman applied an over-the-counter cooling patch to relieve the pain.

But soon, she was calling 911: She suffered a severe allergic reaction to the medication in the pad, causing welts to appear on her swollen and reddened face, neck and arms.

Under the old model of providing emergency medical care, the responding engine from Anaheim Fire & Rescue’s Station 11, with a firefighter/paramedic aboard and two or three other fire personnel, would have started treating the woman at the scene and continued treating her during an ambulance ride to the nearest emergency room.

But thanks to an innovative new pilot program that is the first of its kind in California and one of only two in the country, that call Tuesday in west Anaheim went down much differently.

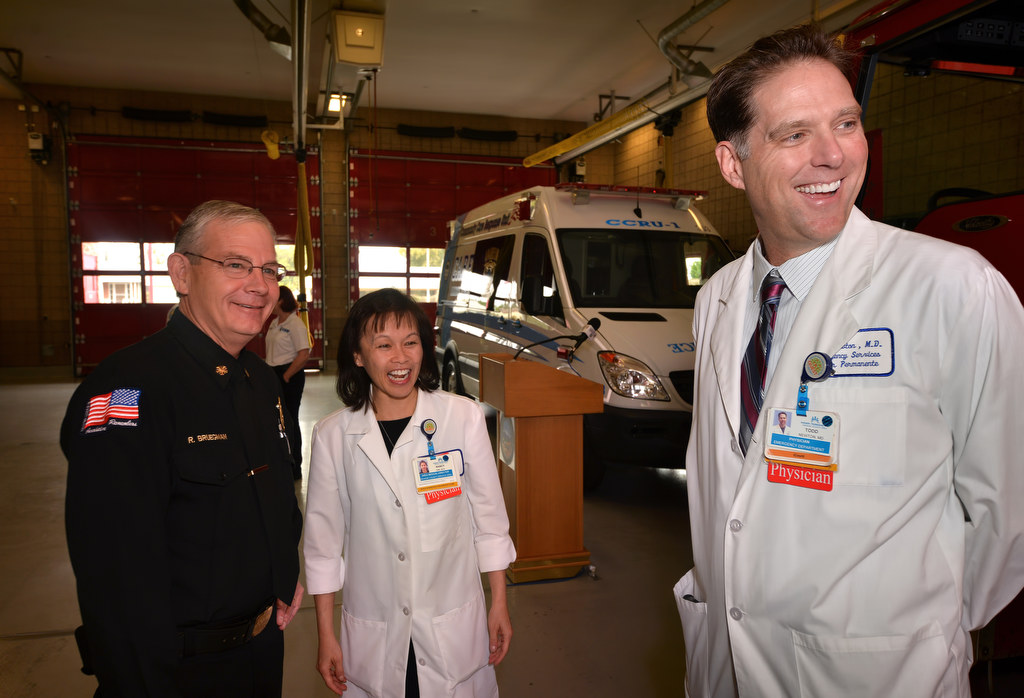

Anaheim Fire & Rescue Chief Randy Bruegman, left, with Dr. Nancy Gin, medical director for Kaiser Permanente in Orange County, and Dr. Todd Newton, Kaiser Permanente’s Regional Chief of Emergency Medicine, during a news conference at Station 11 on Wednesday to announce Anaheim’s new Community Care Response Unit program. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Victoria Morrison, a nurse practitioner, was aboard the specially equipped Care Ambulance that rolled out to the scene with an Anaheim Fire & Rescue engine.

She, along with partner Scott Fox, a captain/paramedic, began advanced life support (ALS) and, after treating the woman at her home with steroids, the swelling and reddening subsided.

Just a few minutes into the 45-minute call, the Anaheim Fire & Rescue engine was freed up for more acute medical or fire-related emergencies.

And the woman avoided a costly and time-consuming trip to the ER.

Welcome to Anaheim Fire & Rescue’s new Community Care Response Unit (CCRU), an ambulance equipped with a nurse and supplies that essentially transform it into an urgent care center on wheels, allowing patients with non-life-threatening issues to be treated at home, resulting in cost savings to the overburdened health-care system.

AF&R Chief Randy Bruegman calls the CCRU a “game changer” in the delivery of fire and emergency medical services in California.

“As health care begins to reinvent itself under the Affordable Health Care Act, there’s going to be more of an emphasis on how fire service agencies can deliver high-quality service in the field that results in excellent customer service and that doesn’t impact emergency departments and hospitals,” Bruegman said.

Anaheim Fire & Rescue Chief Randy Bruegman introduces Anaheim’s new Community Care Response Unit. Standing in front of the new ambulance is AF&R Capt. Scott Fox and Nurse Practitioner Victoria Morrison. Also pictured (from left) are Dr. Gary Smith, physician supervisor for the new CCRU; Dr. Nancy Gin, medical director for Kaiser Permanente in O.C.; Dr. Todd Newton, Kaiser Permanente’s Regional Chief of Emergency Medicine; Bill Weston, director of operations for Care Ambulance Service; and Gary Gionet, manager of Metro Cities Fire Authority (Metro Net) in Anaheim. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

The CCRU is a public-private collaboration between AF&R, Kaiser Permanente Orange County, Care Ambulance Service and Metro Cities Fire Authority (Metro Net).

Formally introduced to the media Wednesday morning at Station 11, which serves a high-density area that has a high volume of calls for medical aid, the CCRU began service May 31 and already has proven its worth, officials said.

During the first 30 days of operation, 40 percent of 56 patients seen by Morrison and Fox did not have to be transported to an ER, Bruegman said.

The CCRU could have a big impact in Anaheim, where 85 percent of the 30,000 emergency calls that come in each year to AF&R are medical related.

Of these 25,000 or so calls, about 35 percent — or 9,000 — fall into the category of “low acuity” cases that may be handled by the CCRU.

Such cases include animal bites, abdominal pain, eye problems, lacerations, leg pain, upper respiratory infections, headaches and non-traumatic back pain.

The CCRU is modeled after a hugely successful program at the Mesa Arizona Fire & Medical Department, which last year saved more than $4 million in health care expenses with three similar ambulances that operate around the clock. The roots of Mesa’s program go back eight years, but the program has been fully operational for the last three years.

The Los Angeles City Fire Department and South Metro Fire and Rescue in Sacramento County also are exploring deploying similar units, according to Bruegman.

Anaheim’s sole CCRU will operate 40 hours a week during its first year — noon to 10 p.m. on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Friday and Saturdays — but Bruegman said he’s hopeful the program can be expanded during fiscal year 2016-17.

“I’m pretty confident…we can make this work here,” he said at the news conference Wednesday.

Kaiser Permanente provided a grant of $210,000 toward the CCRU’s total first-year cost of around $500,000. Care Ambulance provided the specially equipped ambulance and hired Morrison, 40, a well-respected nurse practitioner who beat out dozens of other applicants for the pioneering nursing position.

“It’s great, and it’s a big change from what I was doing,” said Morrison, who most recently worked in internal medicine for a private practitioner in Orange.

Her partner, Fox, 53, is a 28-year veteran of Anaheim Fire & Rescue with more than 20 years of experience as a paramedic.

“The look on people’s faces when they find out they don’t have to go to an emergency room has been indescribable,” Fox said of the reception to the CCRU.

“The first question out of their mouths when we arrive usually is, ‘Who are you?’”

Bruegman said the idea of a CCRU in Anaheim grew out of a strategic plan for AF&R he began developing in 2011 — a plan for the agency to remain competitive, add value beyond the 911 call, and operate more efficiently and effectively.

He reached out to Dr. Nancy Gin, medical director for Kaiser Permanente in Orange County, as well as Dr. Gary Smith, who provides oversight for the Mesa Arizona Fire & Medical Department and who now, after becoming licensed in California, serves as a physician supervisor for Anaheim’s CCRU.

In Mesa, the average waiting time in ERs has been slashed from several hours to 30 minutes or less because of the three specialized community care units, Smith said. He stressed that the nurse practitioners there and in Anaheim are not meant to replace primary physicians.

Capt. Fox points out some of the Advanced Life Support (ALS) capabilities of the CCRU at Wednesday’s news conference. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Rather, in addition to treating patients at the scene, Morrison helps secure appointments with their physicians and follows up with patients three days later.

One of the first patients she and Fox saw was an elderly man who complained of leg pain following recent heart surgery.

He wanted to go the hospital.

Morrison instead called his cardiologist, who scheduled an appointment for him the next day after concluding his patient didn’t need to go to the ER.

Among the attendees at Wednesday’s news conference was Brian Cotter, chief executive officer of Anaheim Global Medical Center, the 188-bed acute care facility formerly known as Western Medical Center Anaheim that is among four hospitals in Orange County operated by KPC Health.

Cotter liked what he saw.

“This saves everyone time and allows (fire service agencies and hospitals) to focus their energies on, and better deploy their resources to, the residents who most need it,” he said.

Capt. Fox and Nurse Practitioner Morrison work four 10-hour shifts per week in the CCRU. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Gin said the CCRU perfectly dovetails with Kaiser’s mission to improve the health of its members and the communities it serves.

“We believe this innovative and hands-on approach will enhance emergency medical services for all residents of Anaheim,” Gin said.

A paramedic engine/truck level response can be requested any time the CCRU crew feels a patient would benefit by being transported to an ER. And the CCRU crew could be called upon if, after a paramedic assessment, the paramedic believes the patient would benefit from the care of a nurse practitioner.

For the first three months of the pilot program, the CCRU will be accompanied to calls by the traditional emergency deployment of a paramedic crew and ambulance. After that, it will go out on its own.

“I think this will probably really take off,” Bruegman predicated of the CCRU.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge