When we look at our hands and fingers, most of us just see a bunch of random lines, squiggles and swirls. But Debbie Mele sees much more than that – she sees someone involved in a crime.

For 18 years now, Mele has specialized in fingerprint examination as a lead forensic specialist for the Orange County Crime Lab. As part of a more than 20-year contract the Crime Lab has with Garden Grove Police Department, Mele works with the agency onsite four days a week examining prints.

“The fingerprints are an amazing tool for identification because they are unique to the individual, they’re formed in utero, before birth, and it is a completely random biological occurrence,” she says.

Not only are the prints formed before birth, but also they remain constant until death – except, of course, if a person tries to alter his or her fingerprints in order to evade capture (which people do). Even then, an expert like Mele often can still spot the patterns that can match prints on a crime scene to an individual in a criminal database.

Debbie Mele, lead forensic specialist at the GGPD, shows how a partial print, left, that would have been unusable in the past before computers and special software, can now reveal enough information to help identify a suspect.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Side-By-Side Examination

The process of fingerprint analysis for Mele begins with a lift card collected by officers or CSI personnel at the scene of a crime. The card contains a print collected in the field, usually with black powder and lift tape. It also contains pertinent identification information such as when the print was collected, who lifted the print and the source of the print (for instance, a vehicle).

If the print on the lift card is useable, Mele starts by inputting the identifying information into the OC Crime Lab’s Cal-ID database and scanning in the print.

The system generates a list of potential candidates throughout the county that have had their prints digitally scanned into the system. It’s Mele’s job to compare the crime scene prints with the prints in the system to find a match. If there’s no match, she can search the California Department of Justice’s database, and if no match is found there, then the FBI database. If no match is found, the prints remain in the system as unknown.

“Fingerprints as a means of identification…it’s yes or no, there’s no gray area,” Mele says.

In other words, once Mele finds a match, she is 100-percent sure about the match. And once she submits her match, another examiner must confirm her findings and then a report is generated.

On occasion (maybe two to three times a year) Mele is called to testify in court about fingerprints. She recalls a case that was a homicide where a woman was killed in her home by someone the woman knew. She was found bound and gagged. A fingerprint was lifted off the sticky side of the duct tape used on the woman. Mele identified the fingerprint. The suspect ended up pleading guilty.

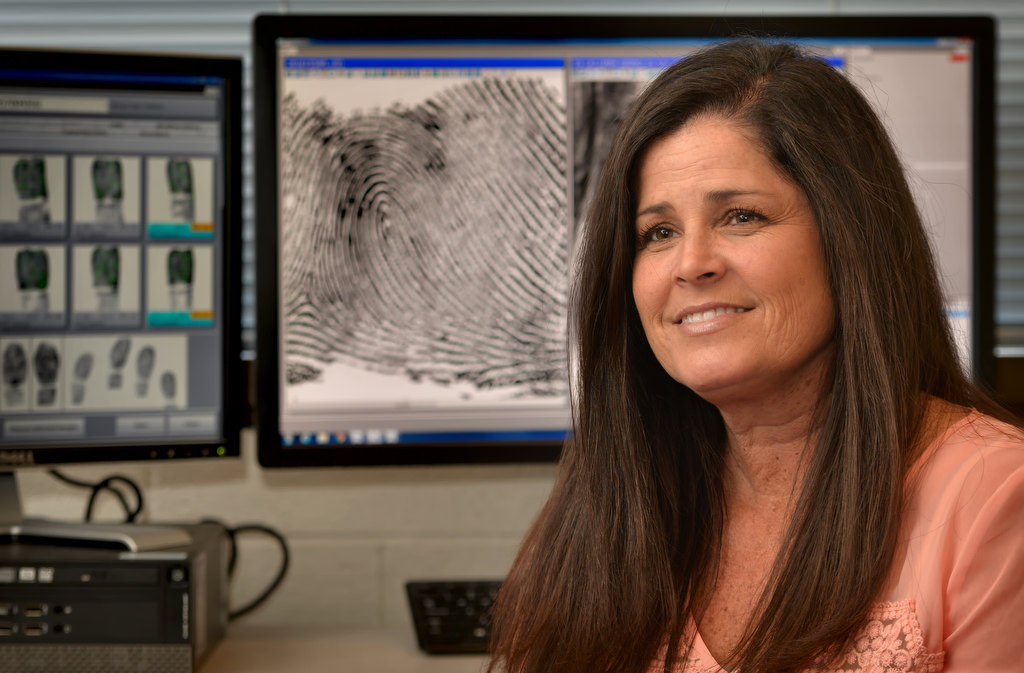

Debbie Mele, lead forensic specialist, uses computers and special software to scan, examine, archive and search for fingerprints to try and match what is found at crime scenes to actual people.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

It’s All In the Details

Every fingerprint lift card is unique. Some can be matched in a minute, some take hours and some don’t get matched at all. Many factors go into the quality of the print: the amount of surface pressure; the amount of debris, dust and other contaminants; and the individual leaving the prints behind.

“A person may go the entire day without leaving a print behind,” she says.

For instance, the older people get, the dryer and more wrinkled the skin becomes, which can make leaving a good print less possible. A hard, nonporous surface will capture the best prints. Another factor coming into play is the transfer substance, which can be sweat, the skin’s natural oil, makeup, blood, etc.

The kind of print it is also determines how it is lifted.

While black powder and tape generally are used to lift a print off of a nonporous surface, there are other more specialized techniques that can be used depending on the circumstances (“We’ve retrieved fingerprints from bodies,” Mele says).

Porous items like paper, cardboard or dry wall are chemically processed with ninhydrin. The prints are then digitally processed and given to Mele as photos for examination.

If there’s a homicide scene with bullet casings left from a shooting, the casings would be collected and fingerprinted. The casings would be fumed with Super Glue in a field chamber, then fluorescent powder would be applied and light used to capture an image digitally so that Mele could examine it.

“There are various types of chemical processes that we use to capture and enhance the fingerprints,” she says.

Mele spends a lot of time at her desk in front of her extra large computer screen staring at arches, loops, deltas and whirls, zooming in on characteristics and going back and forth between known and unknown prints to see if there’s a match.

“It requires a lot of patience,” she says. “It’s a tedious job.”

But…

“It is satisfying (and) gratifying to know that we’re doing our job and helping protect the citizens of our cities.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge