Justice is complicated. It extends beyond law and fairness. It should be about truth, but that’s not always the case. Often it neither comes in time nor paid in full.

The measure of justice for 1974 murder victim Linda Cummings and her family didn’t arrive until nearly 50 years later — and may never have come at all if not for a dogged reporter who couldn’t let the homicide pass unresolved.

Click here to listen to the podcast on Spreaker or Spotify.

In “Murder by Suicide: A Reporter Unravels a True Case of Rape, Betrayal and Lies,” now available on Amazon and other book retailers, reporter Larry Welborn details his enduring quest. A riveting read, the tale is part true crime story, part memoir. The book tells the tale of a staggering miscarriage of justice, a truth plain to see had anyone cared to look, and a system aligned against the victim.

Welborn, who spent 44 years as a staff writer at the Orange County Register, covered more than 500 trials and chronicled the most notorious criminal cases in Orange County history. These ranged from serial killers such as Rodney Alcala and Randy Kraft to the beating death of Kelly Thomas by Fullerton cops. He began his career while in college, writing freelance for German news magazine Der Spiegel on the trial of the Manson family.

Veteran courts and crime reporter Larry Welborn has a new book out, “Murder by Suicide,” about a 1974 cold case that was solved decades later.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

But it was Cummings’ murder to which he returned time and time again. Although the two never met, Welborn never forgot Cummings and he never gave up.

The suspected killer was eventually charged 31 years after Cummings’ death, but was never convicted and died before he could be brought to justice.

Notions of justice

Taken from the Latin justitia, in American law, justice is the system by which those who break laws are investigated, judged, and penalized — at least in theory.

In reality, “Nearly 340,000 cases of homicide and non-negligent manslaughter went unsolved from 1965 to 2022,” according to FBI statistics.

That’s where Cummings’ case was, and still is – at least officially.

Ethically, justice is considered fair, equitable, and appropriate treatment. Together these notions of justice are key to the social fabric. We are called to treat each other fairly through laws and punished when we don’t.

Plato saw justice as virtue upholding societal order. To Thomas Hobbes, justice was an artificial instrument necessary for a civil society. To others, justice addresses inequalities and fosters opportunity. Nowadays, you see the word added to the end of issues legal, social, racial, economic, gender, and environmental. We all want justice.

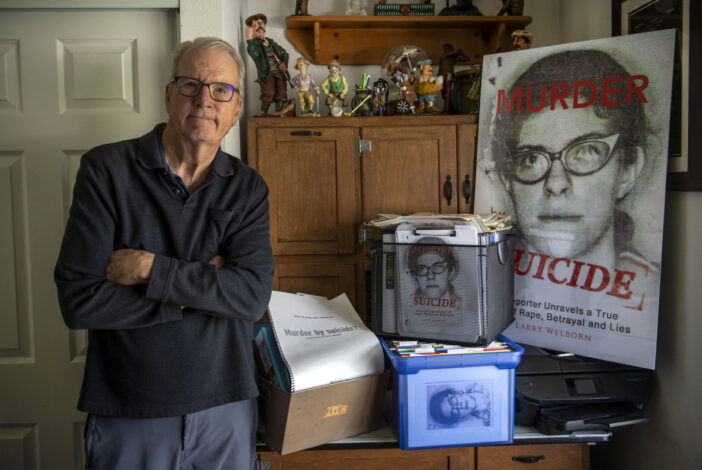

Larry Welborn at his book launch party at Chapter One in Santa Ana for the True Crime story, “Murder by Suicide,”

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Sometimes the only justice is that which the violators impose on themselves. For those who believe in eternal justice and retribution, justice may arrive in an afterlife. Maybe we are denied reward, or return to earth as a maggot.

Cold cases embody the idea of justice reaching beyond the grave. Unable to provide relief for the victim, there can be other kinds of justice: in retribution against the perpetrator or closure for the families of victims, in legacy and memory.

For the deeply Catholic Cummings, clearing any whiff of suicide hanging over her memory may have meant everything. Sometimes, it is about setting the record straight, and if there was ever a guy for that, it was Welborn.

Larry Welborn stands with a poster of the cover of his new book.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Cummings’ death is now officially recognized as a homicide on her death certificate. Any doubts about her demise are removed. Does it suffice? Sometimes you take the justice you get.

To Cummings’ surviving family, however, Welborn’s efforts go a long, long way.

“What (Welborn) did was a wonderful thing, bringing out the truth,” says Paul Broadway, Cummings’ step-brother, whom she babysat when he was young. “She didn’t have to go through eternity with a suicide.”

Time travel

To tell the story requires going back to 1974, a time of Richard Nixon and Watergate, the waning throes of the Vietnam War, and the Rumble in the Jungle boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman.

Missing in the headlines, or anywhere in the papers, was the death of Linda Cummings. Found on a January morning, nude, drugged, and hanging from a clothesline in unit 8 of the rundown Aladdin Apartments in Santa Ana, hers was the kind of story newspapers often avoid.

Larry Welborn with former Orange County District Attorney Tony Rackauckas Jr. at Welborn’s book launch.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

The early investigation relied mostly on statements — all false as it turned out — by the complex’s manager, Louis “Louie” Wiechecki, who said Cummings had no friends, no family, was lonely, depressed, and just released from a mental stay at a local hospital.

Detectives were troubled by the chatty apartment manager, who used his passkey to discover Cummings and was the last to see her alive. Plus, the crime scene looked staged. Wiechecki was the sole source of the information.

A young deputy coroner had his doubts until talking to a chatty man, who identified himself in a phone call as Dr. Marks, and confirmed Wiechecki’s tale, while adding corroborating details, such as drugs in the victim’s system. Under pressure to make a determination, the deputy coroner stamped SUICIDE in red ink on the death certificate, effectively closing the case.

And that’s how it could have ended.

Reporter digs in

As Larry Welborn tells it, he was a rookie reporter assigned to the courts beat at the Orange County Register, and he “absent-mindely bounced a tennis ball at the newspaper office” at the end of that day.

That’s when the phone rang.

“It’s been ringing in my head ever since,” Welborn said.

The call changed his life.

Veteran Orange County Register courts and crime reporter Larry Welborn in the office where he wrote his new book, Murder by Suicide. Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

A weeping and flustered woman named Sylvia Broadway was on the line. She told him about getting the runaround regarding her step-daughter being killed. Welborn had never heard of Cummings. Her death had occurred before he moved onto the courts beat.

“Who killed Linda?” Welborn asked.

“That guy in your article …. Louis what’s-his-name,” Broadway said.

Time stopped. The last sheet of the day’s stories spiraled to the floor, the tennis ball was stuffed in an ashtray. Welborn’s reporter’s senses began buzzing.

Louis Wiechecki? Wasn’t that the guy he had just written about in a story about a suspected murder?

Larry Welborn with former Los Angeles Times writer and friend William Rempel at Welborn’s book launch party.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Just five weeks after Cummings’ death, a woman whose son-in-law was a prominent Orange County physician was strangled at the same apartment complex. After an amateurish and inept effort to cover up the incident as a kidnapping, Wiechecki was charged with murder. And the cops had the goods. It was certainly an odd coincidence.

Although Welborn recalls being immediately intrigued, he had no idea where the rabbit hole would lead. There’s a saying in newspapers: “Important, if true.”

Many times frantic calls from relatives of victims are untrustworthy. But, if true, a double-murder story would be a heck of a way to kick start a reporting career. Welborn figured it would be easy enough to run down.

“I figured I’d make a couple of calls and be done with it,” Welborn recalls.

Larry Welborn’s book launch party was held at Chapter One in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Ten days later, Welborn wrote about Linda Cummings for the first time. He wouldn’t write the rest of the story for decades. It would take 45 years to clear up a final detail, and nearly 50 years for the story to come out in book form.

Although the “who” was obvious immediately, proof and getting the judicial system to act were something else altogether.

Cummings wasn’t considered a murder victim, after all. Back in 1974, police tried to link Wiechecki to Cummings’ death before dropping the prosecution. The latter killing was a slam dunk, so that was the case brought forward. Eventually, Wiechecki would be convicted of manslaughter in that death, do five years, change his name, and leave the state.

Meanwhile, Cummings’ death was reclassified as “undetermined.”

Larry Welborn’s book launch party was held at Chapter One in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Even as police investigations were revolutionized by DNA, CSI, and forensic sciences, and unsolved homicides were revived and solved, Cummings’ case was somewhere beneath those.

Welborn’s book takes the reader through the journey, condensing the decades into a quick-reading 300 pages. The story travels through time, through painstaking searches and investigation, through advances and shortcomings in law enforcement science, autopsies, exhumations, the eventual arrest of the suspect, and the failure of the law to deliver final justice.

Building a career

Welborn couldn’t spend all his time on Cummings. Years passed without progress because no one in law enforcement was actively investigating the case. There was only Welborn.

In the meantime, Welborn was becoming one of the most noted court journalists in the country. He sat in court galleries for the trials of many notorious high-profile killers. The tall, thin reporter who grew up wanting to play baseball and write about sports became the dean of O.C. court writers.

Larry Welborn signs his new book at a launch party at Chapter One in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

He was lauded for his professionalism, accuracy, detail, and straight-forward approach to journalism. He built personal relationships. Those in legal circles said if they gave Welborn information in confidence, at a lunch, in a hallway, or on the golf course, they could always rely on him. That kind of trust takes decades to build and hold. It made Welborn the best-sourced journalist in Orange County and helped him break countless stories. Accuracy and fairness were core tenets.

Welborn married Annie, with whom he recently celebrated a 50th anniversary, bought a home in Chino Hills, and raised a family with three children.

He also spent hours poring over a murder book he created. A law enforcement term for the paperwork in homicide investigation, a murder book includes notes, witness and suspect interviews, autopsy, forensics and other evidence, and photographs. Welborn’s filled a box.

Larry Welborn’s new book launch party was held June 26 in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

With all the responsibilities pulling at the edges of the life of a man his children say never missed a playoff game or recital during their youth, Welborn is not entirely sure what kept drawing him back.

It may have been as simple as the photograph.

Among the early bits of evidence Welborn gathered was a thumb-sized, black-and-white driver’s license photo of Cummings. All business, in cat’s-eye glasses and unsmiling, she stared straight into the camera. It’s a common effect in art, eyes that follow you around the room through an optical illusion. They were like the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg in “The Great Gatsby.”

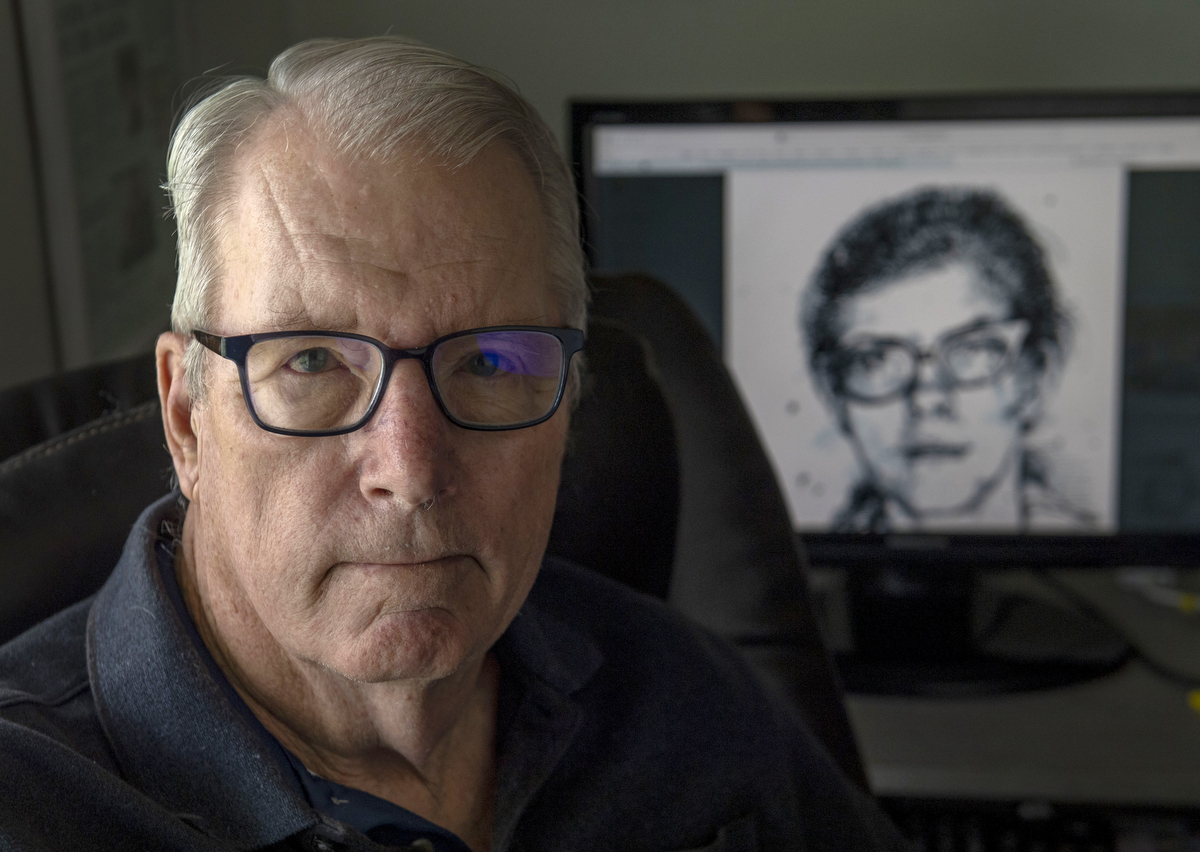

Larry Welborn discusses the cold case that inspired his new book, at his Chino Hills home.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

The photo stirred something in Welborn then and still does. The eyes that followed Welborn didn’t ask for sympathy or protectiveness so much as fairness. Welborn thinks those eyes helped push him through.

Aftermath

At a recent book signing in Santa Ana, Welborn shared a back room at Chapter One: the modern local, a gastropub just a half-mile from where he plied his trade. In a room with an old-time feel, historical photos on rust-colored walls, and black tufted-leather seating, Welborn was surrounded by family, friends, and a number of the key figures in the Cummings saga. Paul Broadway and his sister, Colette, who made the trip from Florida, were on hand.

Also among those on hand and key to bringing the Cummings case back were Larry Yellin, now a Superior Court judge in Orange County, and Mike Fell, a criminal attorney and former Deputy District Attorney.

“I have seen cold cases that have taken years to solve. Almost every cop has that one case that stays with them,” Yellin said. “Put all those together and Larry’s is greater.”

Yellin said hearing from Welborn on Cummings’ behalf, and learning of law enforcement’s failures, “I knew I hadn’t done enough and I was not OK with that.”

More than 30 years after Cummings’ death, Welborn’s reporting and fact-gathering, bolstered by the support of Yellin, then a deputy district attorney, led to the arrest of Wieckecki and a perp walk in front of stunned neighbors in Nevada. Wieckecki was later charged with Cummings’ murder. It was as close to a full accounting as he would come.

In 2009, Wiechecki’s case was dismissed by a judge who said over time too much evidence had been lost, dimmed, or degraded. Wiechecki died of heart failure in 2018.

Cummings’ family felt that in the arrest and perp walk, at least some measure had been delivered. There was one niggling detail: a piece of a paper that still ruled the cause of death as “undetermined.”

Welborn asked Paul Broadway in 2018 whether that still nagged at him, “yeah,” was the reply.

Larry Welborn speaks about his new true crime book, “Murder by Suicide,” at the book launch in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

With the help of Fell, Welborn tackled the issue.

“We went on a journey,” Fell said. “How do you change a death certificate? We weren’t sure.”

Back in court, after delays from the pandemic, without deciding guilt, a judge found the evidence that a homicide had been committed was “overwhelming.” That led to a coroner’s hearing and a change in the cause of death.

“Until I met with Paul, (I didn’t) know how important it was to have that change,” Fell said.

Hugh Nguyen, the O.C. Clerk Recorder, got to make the official change.

“It was the first time I had something like this,” he said. “I knew they would be happy to find out the truth.”

Welborn wrote about Fell breaking the news.

“One of the best calls I’ve ever made in my life,” Fell said.

Paul Broadway was elated, calling it, “the best thing to happen to this family in 50 years.”

“One of the best days in a journalist’s life, too.”

Veteran court reporter and author Larry Welborn discusses the photo that kept him returning to the 1974 cold case that inspired his new book, Murder by Suicide.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

A golfer’s challenge

Welborn became an avid golfer over the years. His home is packed with golf memorabilia and tchotchkes.

In his backyard, Welborn built a small artificial turf golf green between trees with overhanging limbs and across a small ravine and creek on his property. The green is just a short pitching wedge from his homemade tee box. The approach looks both deceptively easy and incredibly difficult, fraught with hazards, requiring precise navigation. Even if you hit the green, how to hold what looks like trampoline-hard turf? And yet, on a display case on the back of his house, sit nearly 100 balls, purportedly from holes-in-one by Welborn.

In a sense, the golf hole is an apt metaphor for Cummings’ case and why, in its way, it uniquely suited Welborn.

At once seemingly straightforward and simple, until you consider all the obstacles and variables. Negotiating the case required practice, purpose, precision, ingenuity, resolve, tenacity, patience, and time.

Lots of time.

Larry Welborn speaks at the launch party for his new true crime book, “Murder by Suicide.”

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Larry Welborn’ with friends and family during his book launch event at Chapter One in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Larry Welborn with Colette Broadway, Linda Cummings’ step sister, at a book launch event in Santa Ana. Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Larry Welborn’s book launch event was held Wednesday, June 26, 2024 at Chapter One in Santa Ana.

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Larry Welborn speaks to the audience at his book launch about the true crime story, “Murder by Suicide.”

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Larry Welborn speaks to the audience at Santa Ana restaurant Chapter One about his book, “Murder by Suicide.”

Photo by Michael Goulding/for Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge