The standoff at the university was getting tense.

A suicidal student had barricaded himself inside his room on the third floor of a dorm.

Sgt. Jeff Schnell, a member of the Orange County Sheriff’s Crisis Negotiation Team (CNT), was running out of ideas when he decided to whip out his harmonica.

An avid musician, Schnell knew the student was majoring in music. So he began playing a blues scale.

The student opened the door.

“What are you doing?” he asked Schnell.

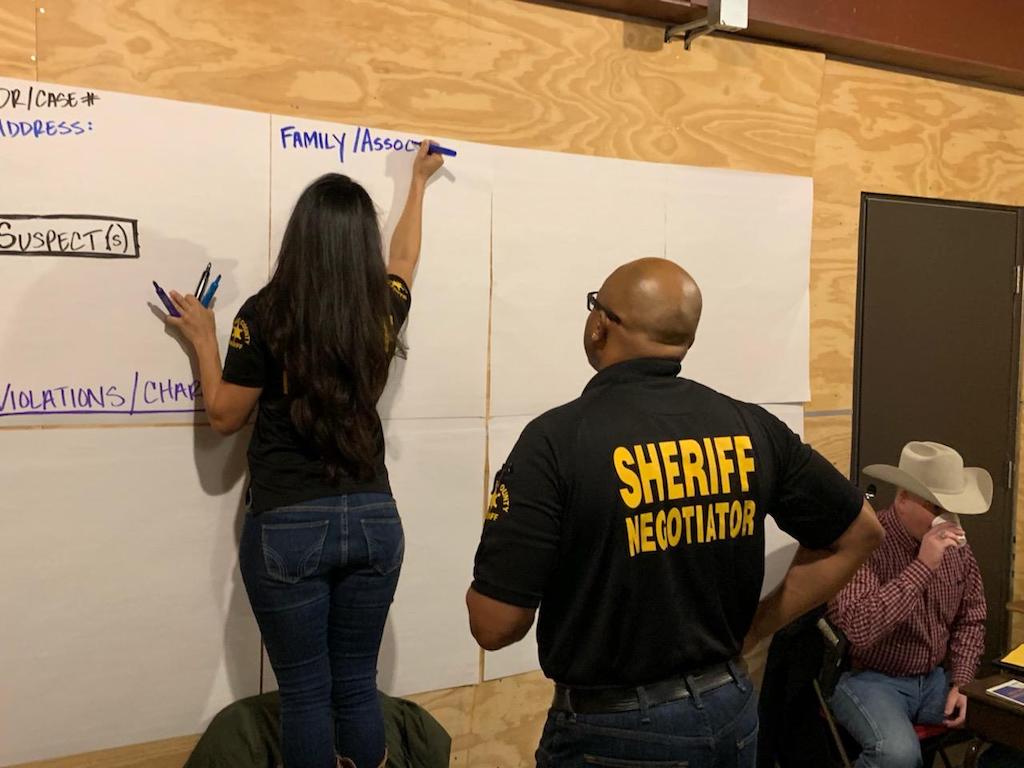

OCSD Deputy Frank Gonzalez, left, and Investigator Calvin Silva work the throw phone during a Crisis Negotiation Team training exercise.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Another deputy stationed behind the door was able to spring out and apprehend the student, ending the drama.

“I’ve done that twice,” Schnell said of successfully ending a crisis negotiation by playing his harmonica.

Trained to respond to hostage situations, barricade incidents, threats of suicide, and high-risk search warrants, members of the CNT, comprised of threes sergeants and 21 operators, often have to get creative.

And the team’s skills aren’t going unnoticed.

The OCSD’s CNT recently nabbed fourth place at an international competition of 30 law enforcement teams hosted by Texas State University.

The showing was, by far, the OCSD’s best in the agency’s third year of participating, said Sgt. Sandra Longnecker. The first two years, the OCSD’s CNT finished near the back of the pack, she said.

The eight-hour competition, in its 29th year, involved a mock-hostage situation evaluated by trained and experienced negotiators. Texas State University students played the role of hostage-takers and hostages.

OCSD Investigator John Blank looks over the department’s Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD), a directional speaker that can be used as a loudspeaker as well as emit an uncomfortable warning tone to disrupt suspects or unruly crowds.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Dr. Michael McMains, a police psychologist, helped launch the event. This year, the competition, which is preceded by two days of training, involved more than 300 officers and deputies.

“If you look at the national data,” McMains said at the competition in Maxwell, Texas, “once negotiators respond to a critical incident, their success rate is about 97-98 percent. What that means is that once we start talking, innocent people don’t get hurt or killed. Police officers don’t get hurt or killed. The bad guy doesn’t get hurt or killed. That’s all the justification you need for making these negotiators better at what they do.”

The CNT currently has openings — it’s an ancillary duty for full-time sworn personnel. On Feb. 14, the team ran eight applicants through three scenarios at the empty former courthouse in Laguna Niguel, at Alicia Parkway and Crown Valley Parkway.

One scenario involved a man who took hostages with a knife inside a family law courtroom after a judge’s ruling didn’t go his way. The other, a two-part scenario, involved a combat veteran with signs of PTSD who went berserk at a cleaner’s run by Persians after they ruined his suit he needed for a job interview the following day. The first part of that scenario was an intelligence gathering interview.

OCSD Sgt. Sandra Longnecker and Investigator John Blank talk about a Crisis Negotiation Team training exercise.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

The day before CNT applicants went through the two scenarios, team members prepared for the scenarios, which included laying a few hundred feet of grounded cable from a trailer known as the NOC, for Negotiation Operations Center, that was connected to a “throw phone” negotiators use on real calls when a subject doesn’t have access to a mobile phone or landline.

Members of the CNT, who get a little extra pay and are subject to callouts 24/7, are extensively trained in active listening and rapport building.

“In a way, it’s like being a counselor,” Schnell says.

The goal in every negotiation is to get a subject talking ASAP. If they’re talking, that means they’re not hurting themselves or someone else.

Negotiations, team members say, is not unlike playing chess – hence the CNT’s symbol of a chess piece, the knight.

Nothing moves linear, usually, on a call. Situations are dynamic, and the unexpected always is expected, CNT members say.

OCSD Deputy Greg Moody, left, and Deputy Brenden Billinger work the mobile command post during a Crisis Negotiation Team training exercise.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

That same night, on Feb. 13, the team had a callout in Dana Point. The subject was in the Marines and alone with guns, and apparently distraught after a custody exchange in which his 3-year-old child was returned to his estranged wife.

Crisis negotiations started via text but ended up happening over the phone. The subject, who shot off numerous rounds — none at deputies — came out less than 10 minutes after he was on the phone, Longnecker said.

Deputies on the CNT strive to control conversations with subjects. For example, they won’t put relatives of a subject on the phone live; rather, they will record 30- to 45-second clips of the relative speaking, and then play the recording to the suspect.

Sometimes, they’ll decide not to play the recording, based on their assessment of whether it will help or hinder negotiations.

OCSD Deputy Frank Gonzalez, left, and Investigators Calvin Silva and John Blank (right) go over strategies for a Crisis Negotiation Team exercise.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

When the CNT is sent out on a call, members fall into distinct roles. The primary negotiator is the one talking to the suspect. The secondary negotiator listens in on that conversation, but keeps one ear free to take in other information and feed notes to the primary investigator.

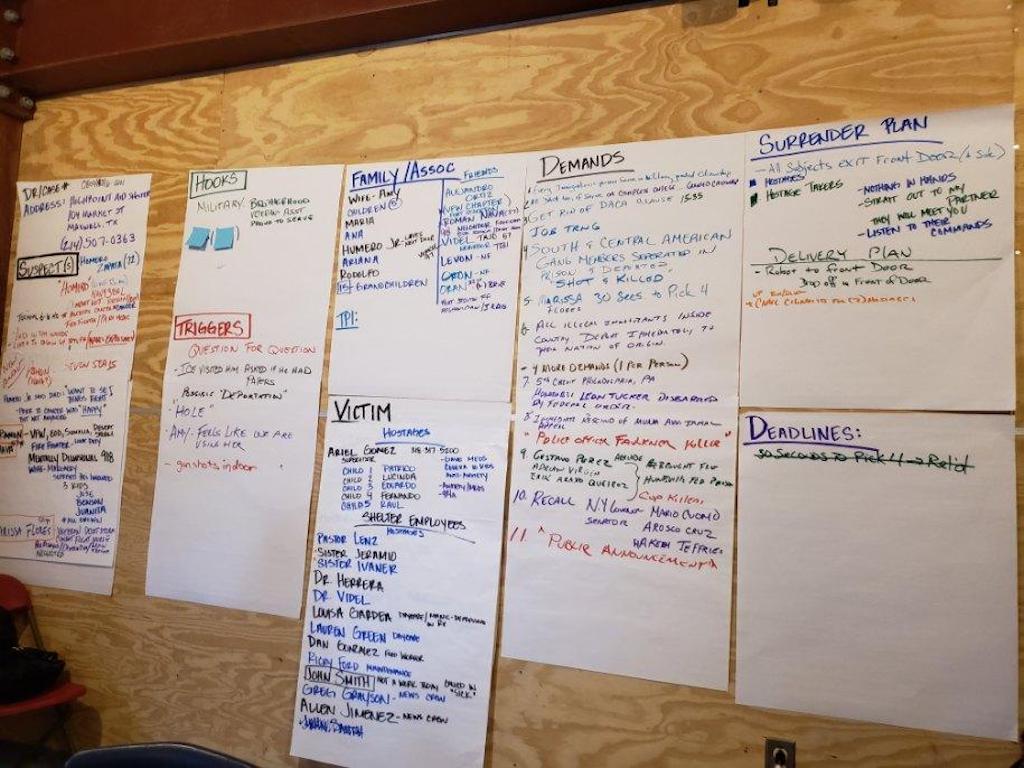

A scribe, typically using whiteboards inside the NOC, writes down all relevant information.

A person is assigned to gather intelligence. He or she will use social media and law enforcement databases to glean as much information as possible on the subject.

Another CNT member acts as a liaison with the OCSD SWAT team, relaying any tactical information gathered over the phone.

When collecting information on a subject, CNT members look for hooks and triggers – hooks being pleasant things, such as a family pet or beloved hobby, and triggers being people that may cause a subject to act on a threat, such as an estranged spouse or a relative they don’t like.

“The secondary negotiator really runs the show,” Longnecker explains.

In addition to placing high at the recent crisis negotiation competition, the OCSD’s CNT has another notable accomplishment: It was the first in the nation to conduct negotiations exclusively on Twitter, when in October 2014 the CNT ended a standoff with MMA fighter Mayhem Miller, who was live-tweeting the situation in Mission Viejo.

Overseeing the OCSD’s Crisis Negotiation Team are, from left, Sgt. Todd Carpenter, Sgt. Sandra Longnecker, and Sgt. Jeffrey Schnell.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Sometimes, CNT members do everything right, but to no avail.

Investigator John Blank recalls a call he said was going great from the CNT’s standpoint. Sadly, after four hours, the suspect killed himself in his car, which was parked near a hiking trail in a residential area.

“It didn’t have the outcome we wanted, but everything was flowing, everything was working, everything was coordinated,” said Blank, an investigator who works out of the OCSD’s Saddleback Substation in Lake Forest.

Blank heard the call go out and was first to arrive on the scene, about three minutes later.

The subject had told a dispatcher he planned to kill himself, and then hung up. It took three or four tries, but Blank got the subject on the phone and began negotiating from the front seat of his car on his work cellphone.

Investigator Jeff Jacques showed up and jumped in the passenger seat to act as Blank’s secondary negotiator.

The subject had gone through a bad divorce and believed his ex-wife had alienated his adult kids from him. He had lost his job due to a back injury and could barely afford to rent a room.

Members of the OCSD’s CNT compete in a recent international competition of 30 law enforcement crisis negotiation teams hosted by Texas State University. Photo courtesy of Sgt. Sandra Longnecker

“The information coming in and going out was working well,” Blank said.

But the subject shot himself.

Another recent call turned out better.

Deputy Brenden Billinger was working patrol the week before Christmas 2018 when he saw a young woman on a bridge on Santa Margarita Parkway in Rancho Santa Margarita that has been the spot of many suicides.

“I saw a female preparing to jump; she was leaning over the rail,” Billinger recalled. “Instead of yelling, I calmly talked to her.”

The deputy told the woman, who was 18:

“Hey, I’m here to talk to you. Can you come away from the edge?”

“No, I’m going to jump. I want to kill myself.”

“Why, what’s going on?”

The young woman started talking about family issues.

“That does suck,” Billinger told her. “That really hurts. I can see why you’re here.”

As he spoke, Billinger got closer and closer to the young woman.

She put one foot down on the pavement.

Billinger put a hand on her shoulder.

Members of the OCSD’s CNT compete in a recent international competition of 30 law enforcement crisis negotiation teams hosted by Texas State University. Photo courtesy of Sgt. Sandra Longnecker

“It’s not going to be easy, and there’s no way to fix this, but we can talk about this,” he told her. “I want to be able to help you, and I want to hear more.”

The woman relented, and Billinger and other deputies made sure she got the help she needed.

Asked what he likes about being on the CNT, Billinger said: “We have one of the most diversified teams in the department, from jail deputies to patrol deputies to investigators on special detail.

“If there’s something we need, we have it on this team. It’s a tight-knit family. We work with each other. We grow with each other. And after every call, we break it down and learn something.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge