Editor’s note: In honor of Behind the Badge OC’s one-year anniversary, we will be sharing the 30 most-read stories. This story originally published June 8.

In some ways, they look the same — darkened, musky rooms with unmarked bottles of oil and a roll of toilet paper on a shelf nearby.

Neon signs glowing in heavily draped windows advertise services.

Beds draped with dingy towels serve as a centerpiece for each room.

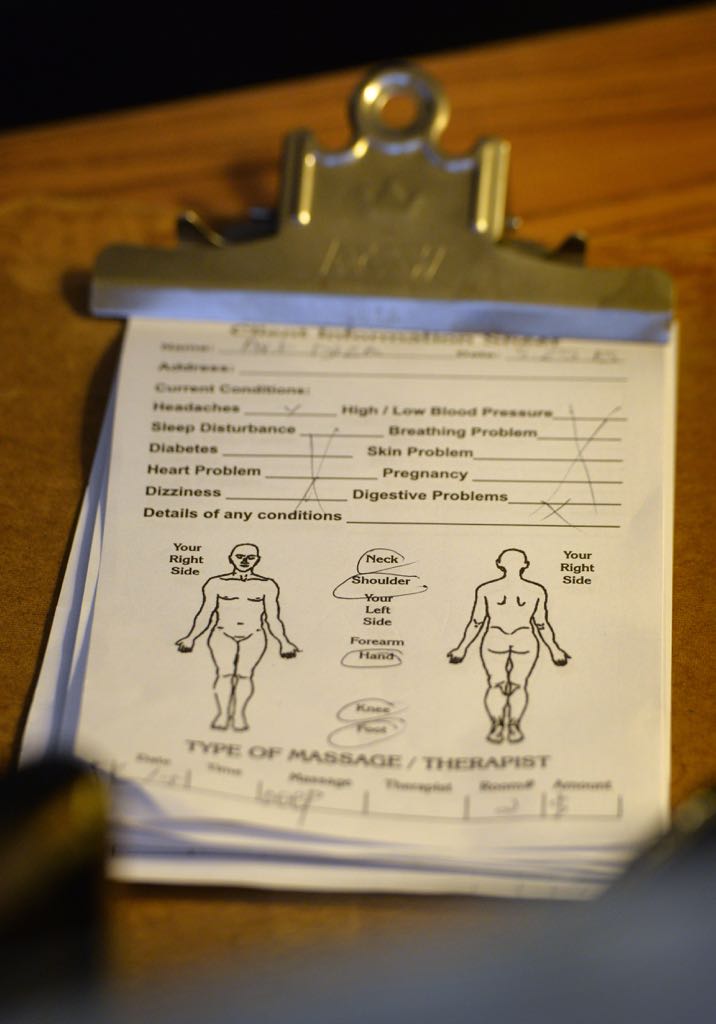

Plastic surgical gloves are stuffed in drawers and customer records are kept on lined notebook paper.

The smell is distinct, and it’s not pleasant.

The business with the Pepto-Bismol pink walls has torn-out magazine photos of Marilyn Monroe and Jennifer Lawrence taped on the wall above bottles of baby powder and lotion.

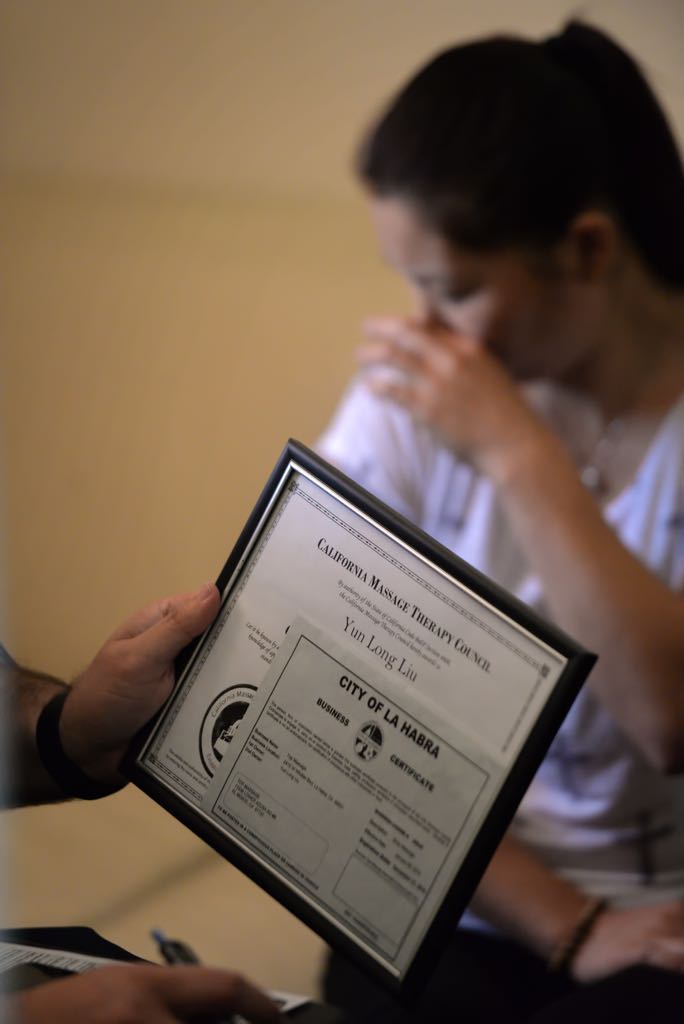

La Habra Police on May 29 ran a sting operation at five illicit massage businesses. Two business were shut down and the task fore handed out more than $8,000 in fines. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Another location has a trash bag full of Coors Light cans and shelves stocked with bottles of Aveeno lotion next to a tidy row of generic brand mouthwash.

Some have signs posted: “No sexual services offered,” but their business practices indicate otherwise.

They only take cash. And, in many cases, female customers are turned away.

Massage businesses, fronting as prostitution operations, are no secret, and they have long been a challenge for law enforcement agencies in Orange County.

In La Habra, the number of massage storefronts have increased six-fold since 2010 — going from four businesses to 27.

Of these, only five are legitimate massage companies, said LHPD Sgt. Brian Miller.

To combat the problem, police are adopting a new approach to shut down these illicit businesses.

La Habra is among the first agencies in Orange County to pair police with city code enforcement and a multi-agency state task force that can fine and immediately close illegal massage businesses.

“Massage parlors have run rampant in the city,” Miller said. “We want to make it so difficult for these illicit businesses to be here that they go elsewhere.”

A sting operation on May 29 that investigated five local massage shops resulted in the immediate closure of two locations and more than $8,000 in state and local fines.

“We anticipate that when these business owners hear the state is going to be coming in and looking at these things it will deter them,” Miller said.

Police shut down a massage business on Whittier Boulevard after workers could not provide proof of worker’s compensation insurance. They were also cited by city code enforcement for not having a proper business license. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

CHANGE IN LAW, LOSS OF CONTROL

Up until six years ago, cities in California had a lot of say in how many massage businesses opened and the areas in which they could operate.

Many had strict zoning laws, and others even instituted caps on massage businesses.

The California Massage Therapy Council was formed in 2009 after complaints surfaced about various massage schools selling fraudulent certificates.

The nonprofit agency’s role includes certifying therapists and tracking massage schools under investigation.

As part of their regulations, cities were required to treat massage businesses as they would any other service — such as a lawyer’s or doctor’s office — and were barred from placing restrictions on how many could open.

Advocates for legitimate massage therapists have said the pre-2009 regulations unfairly impacted legal operators, but police say the change created an ideal landscape for prostitution to flourish.

In 2014, Gov. Jerry Brown signed the Massage Therapy Reform Act, which will require stringent education criteria for massage therapists and give cities more control over enforcing local ordinances.

These changes, which went into effect in January, are expected to reduce the number of prostitution operations fronting as massage businesses, according to state officials.

Over the years, La Habra police have tried approaching the issue from the criminal side by arresting women for prostitution.

“It’s very hard to prove the business owner had any knowledge of what these women are doing,” Miller said. “It doesn’t solve the problem.”

The next approach incorporated city code enforcement, which can fine businesses for a variety of violations, from not wearing uniforms to improper signage.

A sting of five illicit massage businesses resulted in closing two locations on Whittier Boulevard and more than $8,000 in fines. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“Once they feel the pressure and are constantly receiving citations from me, some owners choose to sell their business,” said Urbanie Quintero, Senior Code Compliance Inspector.

But the city process is an arduous one, Quintero said.

City code enforcement must meet a long list of criteria, starting with warnings and citations, before attempting to revoke a business license.

While code enforcement remains an important piece of the puzzle, police wanted an approach that prompted immediate action.

Miller contacted the state’s Joint Enforcement Strike Force, made up of several state agencies, to create a local task force.

The team first ran an operation in March that resulted in shuttering five locations and $9,500 in fines.

The state’s Strike Force isn’t earmarked strictly for prostitution operations. Construction sites, cash-based bars and medical marijuana dispensaries are among businesses they look into that is part what they call the “underground economy.”

But much of their work in Orange County deals with prostitution, state officials said.

Agencies including the Garden Grove PD, Huntington Beach PD and the Orange County Sheriff’s Department have partnered with the state to run prostitution stings.

“(The state) has the ability to go in and give a significant amount of fines and shut down the business owner,” Miller said. “They have the power to do what we can’t as a local agency.”

STRATEGIC STING

The team of eight walked into the small business off Whittier Boulevard.

Police first secured the area and asked the two women who worked there to wait to be interviewed.

As part of these operations, police also look for any indicators that could signal human trafficking, which can be common in the prostitution industry. During this sting, police found that wasn’t the case, Miller said.

Both women said that day — Friday, May 29 — was their first day on the job. This phrase was repeated by all but one woman of the six interviewed in the five-location sting.

One woman wearing black leggings and a low-cut top had keys to the door and more than $400 in her wallet. Four Welfare cards under four different names were found with the cash.

Investigators interviewed the women — they replied in broken English and said they didn’t understand.

State investigators called a Mandarin translator to help.

A man walked up to the back door during the interviews and was met with a La Habra police officer.

“Looks like I have the wrong place,” the man hurriedly told the officer before turning to go back to his car.

The officers quipped about the man’s foiled plans.

Heavily draped windows and neon signs like these often alert officers to a potential illicit massage business. La Habra Police on Friday, May 29, ran a sting operation to target the illegal businesses. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Quintero found several violations, including lack of a business license.

State investigators found the business also did not have proof of worker’s compensation insurance or payroll records.

They ordered it shut down and handed the woman with the cash, keys and Welfare cards the citation.

She clutched her chest, cried out and slumped to the ground. The officers told her to relax and breathe.

Police called for medics but when help arrived, the woman’s breathing returned to normal and she refused treatment.

They watched as the women left the building and locked the door behind them.

Although they successfully closed the business, Miller said he wouldn’t be surprised to see another business under a different name open at the same location.

“It’s like a revolving door,” he said. “And there’s nothing we can do right now to stop them from coming in.”

But they continue to try.

By partnering with the state and working to update its own zoning restrictions, La Habra is making life exceedingly more difficult for illegal operators.

“Until you’re in compliance, I’m going to keep coming back,” Quintero tells the business owner at another location as she hands over a citation.

The 70-year-old woman is on the hook for more than $2,000 in city and state fines.

“I can’t pay, I have no money,” she says. “I (will have to) close.”

And that’s exactly the goal.

Customers can fill out a sheet telling their therapist where they’d like the massage to focus. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

La Habra has more than 20 illicit massage business operating in the city. Police have initiated a multi-agency task force to target the problem. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge