The so-called “militarization” of police has become a topic of much conversation since the officer-involved shooting in Ferguson, Mo., exploded on the national scene in August.

The issue is expected to remain a topic of debate in the coming months as we await the introduction of a Congressional bill that would prohibit the transfer of military equipment to state or local police agencies under the Defense Department’s 1033 program. Beneath all the noise lie a few simple facts:

Modern police equipment protects our communities and police officers from the threat of serious injury or death every day. And the threat has escalated since the horrific Columbine High School shootings in 1999, according to a recent FBI report.

Several tragic active shooter mass-killings since then have made it critical for police agencies to modernize their tools and equipment. The sad reality is police agencies must protect their communities against some of the most heavily armed and dangerous criminals in U.S. history.

Boyd is President of the California Police Chiefs Association’s Board of Directors and Chief of Police in Citrus Heights

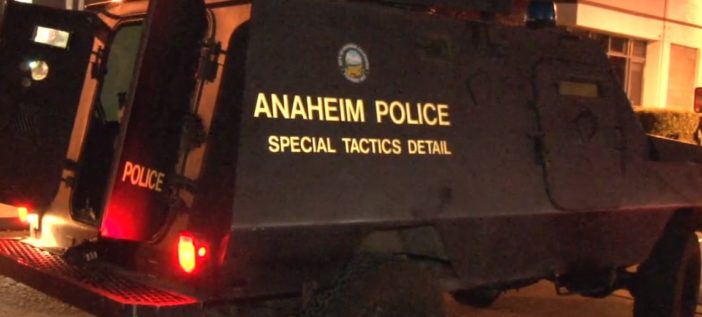

In Southern California, armored vehicles recently stopped dozens of rounds that suspects fired at police officers in Anaheim, San Bernardino and Los Angeles. In July, three heavily armed bank robbers who shielded themselves with hostages fired hundreds of rounds at Stockton police during a deadly hour-long pursuit.

More than a dozen police cars and a police armored vehicle were struck by gunfire. Without such equipment, the outcomes of these incidents could have been tragic, with officers suffering injuries — or worse.

No police chief I’m aware would allow his or her department to become “militarized.”

To the contrary, police leaders have taken great steps to modernize their equipment and community policing philosophy.

The not-so-subtle implication of the term “militarization”– that cops have some kind of warrior mindset – could not be further from the truth.

Police officers see themselves as peacekeepers, not warmongers. And all across our state and nation, examples abound of police departments partnering with their communities to solve problems. It’s among the reasons we’ve enjoyed a sustained crime drop over the past two decades.

Tragically, however, violence remains a daily reality. And so does violence against police officers. And some of the devastating weapons that today’s criminals possess and use can easily penetrate light-armored vehicles and personal body armor.

Critics of the 1033 program rarely mention that the equipment is rarely deployed or that the way police use the equipment differs greatly from the way military uses it. As one example, police use armored vehicles to rescue people under fire and to protect officers. The military uses them to patrol.

Critics also fail to mention that the program provides many non-weapon surplus items, including office furniture, specialty tools and an array of other items like tents and water purification systems that can be used immediately during times of disaster.

Additionally, it’s a gross misconception that all or most of police protective equipment is military surplus. In fact, few items come from the military. Most is purchased by police agencies from police vendors. Something else worth noting: A military source told us that unclaimed military surplus items not transferred to other entities, including MRAP (Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected) vehicles that cost American taxpayers $500,000 to $700,000 each simply are destroyed to keep them out of the wrong hands.

Law enforcement agencies also use the equipment for training. The proposed bill not only is misguided, but also potentially deadly. If it passes in its current form, citizens and police officers that could have been protected will be at much greater risk.

We certainly support responsible changes that will bring greater accountability to the 1033 program, but eliminating its most important aspects would be a huge mistake. We recognize that some of our equipment and tools have become politicized. It’s important for every police agency to be sensitive to public perception and deploy the equipment only when necessary.

But it’s also crucial not to allow politics to cloud the real issue when it comes to protecting our communities – and our police officers.

Boyd is President of the California Police Chiefs Association’s Board of Directors and Chief of Police in Citrus Heights

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge