The boss walked out of his office to see his employee sitting on a curb, hands cuffed behind his back.

“You good, Mike?” the surprised auto repair shop manager asked his mechanic.

His boss didn’t know it, but the 56-year-old mechanic had been convicted of committing lewd and lascivious acts with a child 14 years or younger in 1997.

“Yeah,” Mike said, avoiding eye contact with his boss. “It’s something from my past.”

Anaheim Police Det. Laura Lomeli, accompanied by sex crimes Det. Phillip Han, brought Mike into the harsh light of the present.

As a sex offender registrant, Mike is required to register his address with police every year within five days of his birthday.

He’s a month overdue.

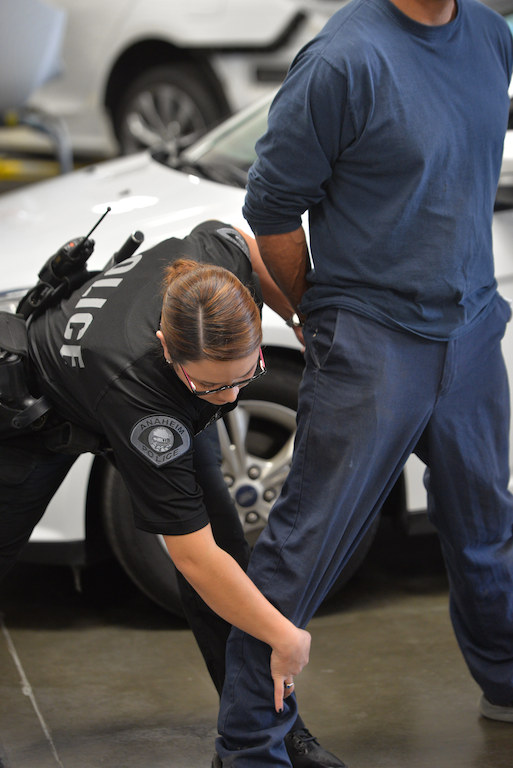

Lomeli pats down a past sex offender she placed under arrest at an auto body repair shop. He had failed to check in with police as required every year. Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“I have a lot on my mind,” Mike tells Lomeli, an officer with a cheerful disposition who wears black nail polish and carries a pink smartphone. “It just totally slipped my mind. I woke up in a panic this morning.”

“You’re a month late to be waking up in a panic,” Lomeli tells Mike, who is picked up by another Anaheim cop to be driven to the station for booking.

Once a month on Monday, usually starting at 5 a.m. before most registrants have left for work, Lomeli and a detective team up to make compliance checks on registered sex offenders.

The number of registrants in Anaheim constantly changes but on this recent Monday it totaled 530 — 413 residents and 117 transients.

Many are on parole and wear a GPS device for monitoring.

Some are not living where they say they are.

Some are in the wind — in cop parlance, UTL, for unable to locate.

Says Lomeli of sex offenders: “Regular members of the public appreciate what we’re doing, but these guys don’t like me.” Photo: Steven Georges

Lomeli, 33, is the sole Anaheim cop tasked with checking on this population in the shadows, although she always teams up with a detective for safety reasons.

All registrants — almost exclusively male and middle-aged — must notify law enforcement of any change in residence within five working days.

Transients must register every 30 days.

Sexually violent predators, the most serious category of sex offenders, must register every 90 days.

And registrants like Mike must check in annually within five days of their birthday even if they’re living at the same address.

“Regular members of the public appreciate what we’re doing,” says Lomeli, a 10-year Anaheim PD veteran, “but these guys don’t like me.”

Lomeli’s generously decorated work cubicle at the Orange County Family Justice Center, located in Anaheim near the police department, is filled with fresh flowers and chocolates, plush toys and trinkets from her alma mater, UCLA, as well as feel-good, inspirational sayings:

Creativity is Contagious. Pass It On.

If You Change Nothing, Nothing Will Change.

Everyone is the Age of Their Heart.

It’s a happy space that starkly contrasts with the ugly and sad nature of her work.

“I don’t understand them,” Lomeli says of sex offenders. “I don’t comprehend why they do what they do.”

Lomeli was part of the team of Anaheim PD officers who worked on the recent high-profile arrests of two sex registrants charged with raping and killing four prostitutes. If convicted, Franc Cano and Steven Dean Gordon could face the death penalty.

“That was a once-in-a-lifetime case,” Lomeli says.

Working the Sexual Assault Detail at the Anaheim PD can be sad but very rewarding, she says.

Det. Laura Lomeli of the Anaheim Police Department’s Sexual Assault Detail (left) goes over the cases of convicted sex offenders they need to visit that day with Investigator LadyCarla Cashell, on loan from the Safe Schools Gang Intervention detail, and Officer Yesenia Escobar from Community Policing, right.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“I try to remind myself that 100 percent of what I read (at work) isn’t how the whole world is — that these (offenders) are only a sliver of the population,” says Lomeli, who has worked on the detail for almost three years.

“Just reading about some of the worst things people can do to each other can be stressful, but when I can help put these people away for a long time, it’s really rewarding. I kind of help give back to victims some power and control over their own lives.

“Once these victims are scarred, they’re scarred for life.”

Lomeli and Han, driving in Lomeli’s unmarked silver Nissan Altima, pull up to the El Dorado Inn on Lincoln Avenue.

They greet the receptionists sitting behind thick, bulletproof glass in a lobby filled with Valentine’s Day decorations.

A shirtless man in boxer shorts answers the door to a room.

“We’re just here to do a quick probation check,” Lomeli says.

“Yes, ma’am.”

The man, on federal probation for a possession of child pornography conviction that put him behind bars in Texas for four years and two months, puts on a T-shirt and sits on a pullout bed. He’s lived in the motel for six weeks. He survives on disability checks.

A Carl’s Jr. cup sits on a counter next to bananas.

A box of Chicken Biskit snack crackers is on a nightstand next to his bed.

His bathroom mostly is bare, except for medications for bipolar disorder.

Lomeli picks up the man’s later-model cell phone.

“Are you allowed to have Internet access?” Lomeli asks him.

“That phone doesn’t have any of that,” he says.

She checks for a web connection and pornographic photos.

The phone is clean.

Lomeli and a separate team of officers check on a total of 19 registrants on this morning.

One of Lomeli’s first stops is to arrest a 61-year-old man with nine prior convictions for indecent exposure.

There’s a warrant out for his arrest because the last time he was at Orange County Jail, he exposed himself to a jail employee.

“I’m pretty familiar with this guy,” Lomeli says.

But by the time Lomeli and Han pull up to the halfway house where he lives, he’s already left for an appointment. Lomeli calls his probation officer to tell the P.O. she is looking for him.

And so the morning goes — lots of knocking on doors, lots of registrants not home, a couple of arrests made, and then Lomeli, an economics major from UCLA who got interested in police work after meeting several cops while waitressing at Marie Callendar’s, returns to her workload of about 30 active sex-crime cases.

“It’s fun and gets me out of the office,” Lomeli says of her monthly sweeps of “290s,” which refers to the Penal Code section that described the Sex Offender Registration Act.

“And unless we check on these people,” Lomeli says, “how do we know if they are where they say they are?

She adds: “We’re trying to make sure these people are in compliance, and if they aren’t, it’s a nice feeling to know we’re helping put away bad people who are likely to reoffend.”

Lomeli checks the cell phone of a sex offender on federal probation to make sure it doesn’t have an Internet connection or pornographic material. Photo: Steven Georges

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge