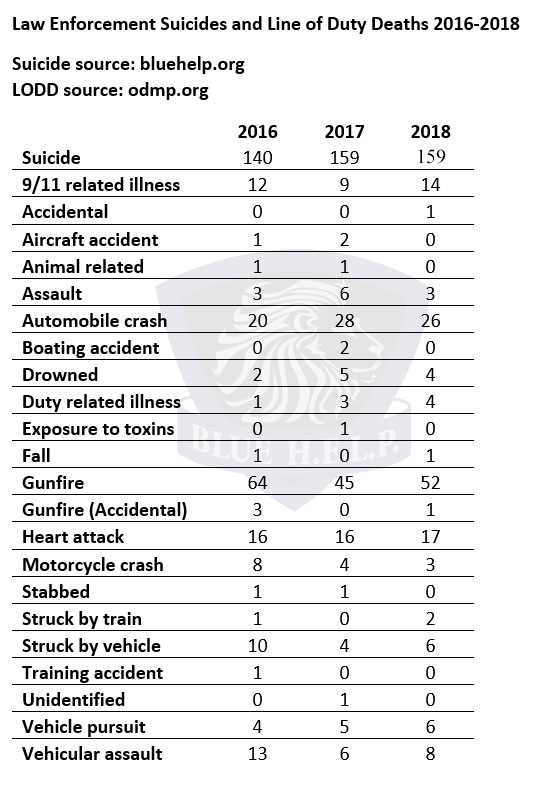

Those who follow law enforcement may know that last year, 150 police officers died in the line of duty, while serving and protecting the community. They left family, friends, and loved ones behind to pick up the pieces.

What you may not know is more police officers took their own lives last year than were killed at the hands of another person. According to the non-profit Blue Help, 159 police officers died by suicide last year. There were no broadcast funeral processions or memorial services for them.

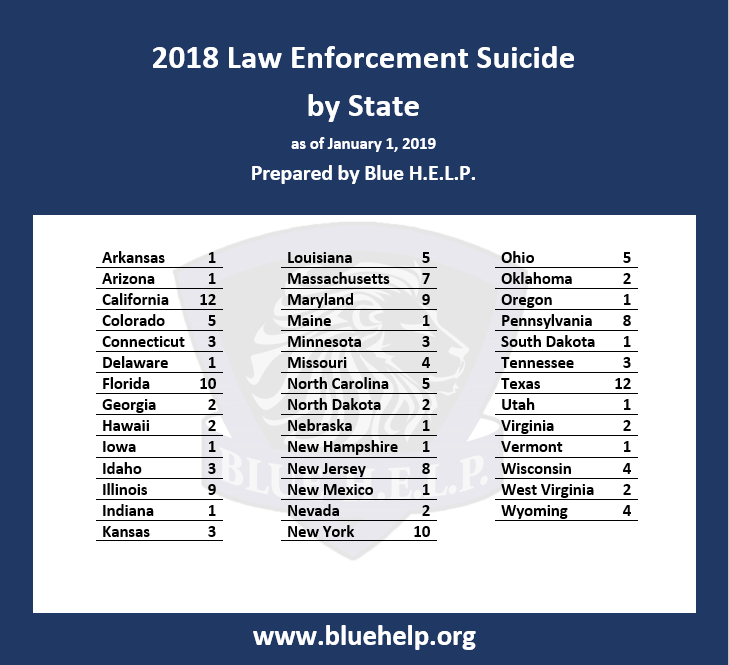

The number of officers who die by suicide has exceeded those killed in the line of duty over the last three years. Graphic by Bluehelp.org

In December 2018, 20 police officers took their own lives. The occupational risk of suicide in the police profession is a serious problem and one that needs to be taken seriously and studied.

Blue Help admits its data is incomplete. There is no mandatory reporting agency for police suicide, so most data is gathered from submissions and news accounts. No one is really keeping track of what is evidently an occupational risk.

Five officers from the City of Chicago Police Department have committed suicide in just the last six months. This has reached crisis level and emergency measures are taking place to try and stop the trend.

I worked for a medium-sized police agency for 30 years and during my time three officers from my department took their own lives. All were unexpected and shocked us. In what other workplace can you say your friends are killing themselves?

Another area where the data only paints a partial picture is the number of retired police officers who take their own lives. The impact of a career in policing can have lifelong consequences.

In November 2018, in a case that was most likely a suicide by cop, a retired police chief from the City of Oakdale was shot and killed by Fresno Police Department officers when he charged them with a knife.

Just this month, a highly decorated retired Long Beach sergeant pulled into a police substation parking lot and took his own life while he sat in his vehicle.

In often-cited research, Dr. John Violanti cites a 69 percent higher risk of suicide for those in the policing profession. His research is extensive, but he admits the data needed to develop effective prevention strategies and treatment options is lacking.

There is no doubt police officers are exposed to more trauma than most people will ever see. How many bodies have you seen? How many of you have dealt with families in crisis, traffic accident victims, sexual assault victims, and gang violence? This exposure doesn’t happen every once in a while, but happens every day for police officers.

There is also no way to measure the impact of negative public sentiment. A constant bombardment of negative news stories and social media rants does have an impact over time. What happens when you see yourself as the “good guy” but seemingly no one else does?

In a Behind the Badge interview, Dr. Nancy Bohol-Penrod said, “Imagine a job where you are almost never off-duty. You are constantly in first-responder mode no matter where you go or what you’re doing. It’s what the job does to you. Over time, that can cause problems. We weren’t meant to live that way.”

“Then there is the job itself. Shift work is terrible both physically and psychologically. The schedules are not conducive to healthy living. For many, you don’t know from day to day if you’re going to get a call in the middle of the night to respond. For lots of first responders, their relationships with their partners ends up being one where they are just ships passing in the night.”

Law enforcement agencies have made significant improvements over the years in addressing the mental health needs of first responders. From peer counseling to contracting with mental health providers the services have improved. However, agencies still struggle to overcome the stigma of reaching out for help.

Many agencies have made counseling and critical incident debriefing mandatory after major incidents where there has been a strong emotional impact. The officers no longer have to reach out but are expected to participate.

First responders are at the frontline of dealing with the every day dysfunction, disorder, and violence of this crazy world. These occupational hazards go beyond the physical and their effects can last a lifetime. We owe it to our law enforcement officers to provide the best in keeping them well and healthy for a career and a lifetime.

Resources can be found for first responders and their families at the National Police Suicide Foundation and Blue Help.

Joe is a retired police captain. You can reach him at jvargas@behindthebadgeoc.com.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge