The veteran CSI specialist grabbed some disinfectant wipes and began cleaning the interior of the van.

“We have a very dirty job,” said Senior Forensic Specialist Kelli Cogert, of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department Crime Lab Identification Bureau.

At the start of a recent 6 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. shift, Cogert cleaned parts of the interior of her work van, which is shared by other forensic specialists, as she prepared to roll to the scene of a commercial burglary in Yorba Linda.

Although Cogert’s job can, indeed, be very dirty at times, it’s also one of the most vital components of law enforcement investigations: collecting and analyzing evidence that can help lead to convictions of suspects ranging from burglars to rapists to killers.

With National Forensic Science Week kicking off today, Monday, Sept. 17, specialists like Cogert are in the spotlight as their painstakingly detailed, and frequently fascinating work, is celebrated.

Cogert, 45, has been with the OC Crime Lab for 22 years, dusting for fingerprints and other markings left behind at crime scenes —- some of them horrific.

On Tuesday, Sept. 18, the OC Crime Lab, located in the Brad Gates high-rise office building across the street from OCSD headquarters on Flower Street in Santa Ana, will introduce recently implemented technology that will significantly advance DUID (driving under the influence of drugs) testing in Orange County. The new technology allows scientists to test suspected impaired drivers for more than 300 substances, including prescription and synthetic drugs, up from 50 substances with the older technology.

When Cogert began her career more than two decades ago, CSI had yet to explode in popular culture thanks to hugely successful TV shows that may have fictionalized the work, but opened the eyes of the public to a career rooted in the hard sciences as well as photography.

OC Crime Lab Identification Bureau Senior Forensic Specialist Kelli Cogert uses a flashlight to help find fingerprints on the outside and inside handle of a door whose glass was shattered by a burglar to gain access to an eye doctor’s office. The perp or perps made off with several thousand dollars worth of high-end sunglasses.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“This job takes a special person, it just really does,” says Cogert, whose father, William Brown, is a retired detective with the Santa Monica PD and whose mother-in-law performed CSI work for the same agency.

“We’ve had people come through here where this job was not what they expected or they just couldn’t handle some of the aspects of this job — blood being one of them,” Cogert said. “How often in your life have you been exposed to a dead body or massive amounts of blood? Most people would say never.

“A lot of times, you don’t know going into a job like this if you can handle it or not. You just don’t know. Your mind keeps saying, ‘Oh yeah, I can handle this, it’s the coolest thing ever,’ but then you get into an autopsy or a situation where there’s a dead body, and the smell just throws you over the edge.”

Cogert grew up interested in law enforcement and crimes scenes, but initially didn’t know if she could handle them.

“But I ended up being just fine,” Cogert said. “There are definitely moments like, ‘Oh my God’ – certain crimes and deaths where I think, ‘How can someone do that to another person?’

“I’ve given up trying to figure out why people do what they do, because it makes me crazy. I’ll never figure it out.

“That’s why it’s so important to have amazing co-workers and an amazing support system. I work with amazing people, and we talk to each other about anything, and I have a great family and I can talk to them about anything.

“There are always people we can talk to if things are affecting us the wrong way.”

On this recent weekday, there would be no such hardcore calls — just the commercial burglary in Yorba Linda. During the rest of her shift, Cogert was able to catch up on reports involving officer-involved shootings.

As a senior forensic specialist, her job is multi-faceted.

Broken glass is scattered on the ground where a burglar shattered a locked door to gain access to an optometrist office in Yorba Linda. Kelli Cogert, a senior forensic specialist at the OC Crime Lab Identification Bureau, examines the area for clues that hopefully may lead to the suspect’s identity.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

In addition to field work, Cogert is trained in evidence processing, impression evidence comparison, and 3D digital scanning for crime scene reconstruction, to name a few of her skills.

She also performs technical and administrative reviews of reports, assists in training new staff, verifies impression evidence comparisons, assists in writing and implementing new procedures for the ID Bureau, and manages the OC Crime Lab’s fleet of vehicles.

“She’s my go-to person when a high-profile case comes, and all the supervisors rely on her experience when it matters,” said Omar Lazo, supervising forensic specialist.

“There isn’t anything I wouldn’t trust her to do.”

At 6:53 a.m., Cogert called the owner of the burglarized business, an optometry office, located in the 17000 block of Yorba Linda Boulevard. The suspect or suspects made off with several thousand dollars worth of brand-name sunglasses.

“I’m calling about your business that was broken into,” Cogert, one of six forensic specialists working this shift, told the victim over the phone. “I’ll be there as soon as I can, thank you.”

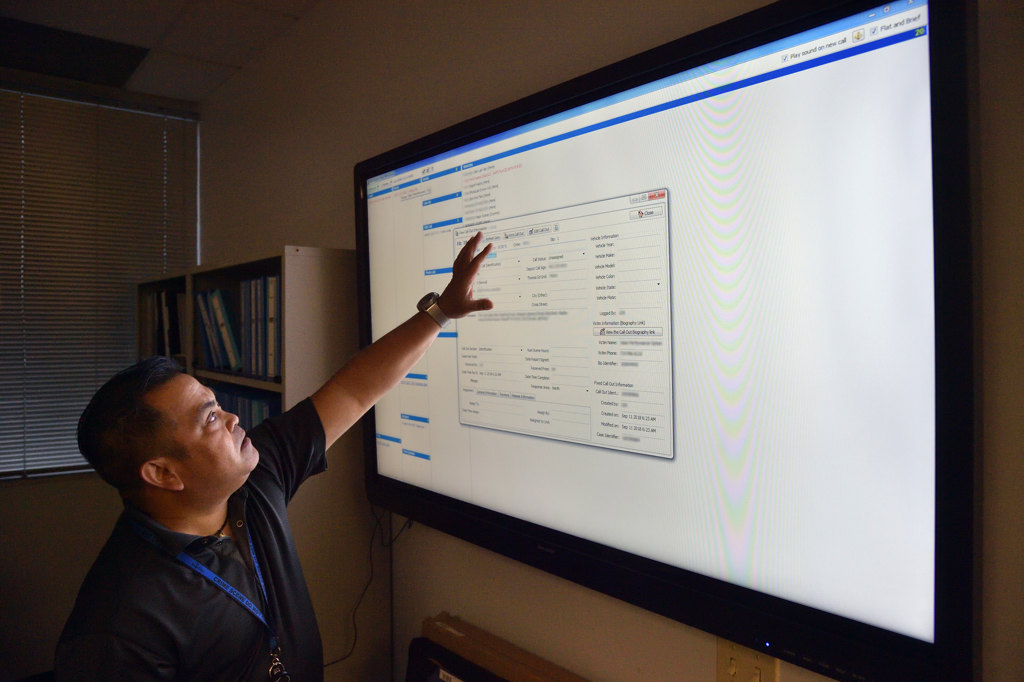

The burglary was one of a handful of calls listed on a universal white board in the sixth-floor office of the OC Crime Lab. The white board actually is a 60-inch flat screen that electronically keeps track of all calls in progress.

That day, the CSI team also was working an autopsy (they photograph them) and two homicide cases, as well as a domestic violence incident. There also was a car, which was connected to a possible homicide suspect, in a vehicle exam area ready to be analyzed.

Cogert and the other CSI specialists never utter the Q word, but that day was, actually, relatively quiet.

Kelli Cogert, a senior forensic specialist at the OC Crime Lab Identification Bureau, lifts fingerprints from an optometry office in Yorba Linda that was broken into by a burglar early Sept. 11.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

OC Crime Lab CSI specialists not only handle OCSD calls; they are available to any law enforcement agency in the county. Overall, they respond to between 3,000 and 3,500 calls for service every year.

The majority of calls are property crimes. The team handles, on average, between 20 and 40 homicides per year.

Between 1:30 a.m. and 6 a.m. every day, when no CSI specialists are scheduled to work, they take turns being on call.

Back in the day at the OCSD, CSI work used to be performed by sworn deputies. Lazo has been in the unit for 18 years. He started in the photo lab as a forensic specialist, then moved over to the field division.

“The department now is a lot more specialized,” said Lazo, meaning CSI personnel these days tend to specialize in certain areas. For example, Cogert is one of three in the OC Crime Lab who is specially trained in footwear/tire-track examinations.

By 7:10 a.m., Cogert is on her way to Yorba Linda. The van, packed with equipment, rattles down the freeway.

The burglars smashed through a locked side door of the optometrist’s office. Shattered glass was scattered in the parking lot and the entryway.

Motion detectors tripped the alarm, and the optometrist got a call just before 4 a.m.

The optometrist, looking very unhappy, told Cogert it’s the second time her office has been hit. She will have to pay for the damage and the stolen sunglasses herself, she said, since getting insurance for a burglarized office is difficult. She said she has no insurance.

At crime scenes, Cogert doesn’t necessarily need to know what’s been taken, but from where — that’s the key.

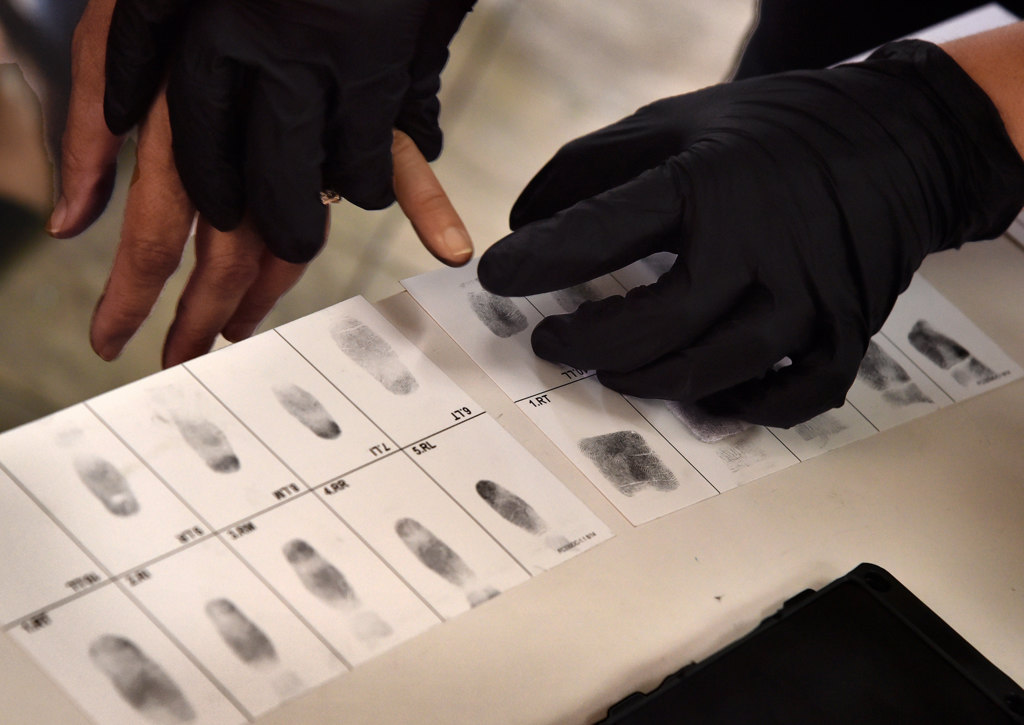

OC Crime Lab Identification Bureau Senior Forensic Specialist Kelli Cogert gets elimination fingerprints and palm prints from an eye doctor whose office was burglarized.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

She trained a flashlight to look for shoeprints on a poster that used to be on the shattered glass door.

None.

Cogert took photos of the scene.

She looked for fingerprints by dusting black powder on the doorframe. She lifted some prints with fingerprint tape and put the tape on a fingerprint lift card.

“They’re not very good,” Cogert said, “but you see some detail right there. We have amazing people that can do wonders with even partial prints.”

Cogert also checked for “dust disturbances” on surfaces.

Then she collected elimination finger and palm prints from the doctor.

“You don’t have video security?” Cogert asked the doctor.

“Unfortunately, no,” she answered.

The call was over by 8:21 a.m. Cogert slowly made her way back to Santa Ana, in case another call came in and she had to respond.

Cogert, who earned a degree in criminology from California State University, Fresno, said her work schedule of 6 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. four days a week works well for her because it allows her to enjoy three-day weekends with her husband, a manager in the home-building industry, and their two sons.

Senior Forensic Specialist Kelli Cogert wipes down parts of the inside of her work van at the start of a recent shift.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“They know that mommy helps catch bad guys, but they also know I’m not a cop,” Cogert said of her sons.

Cogert and her family have two dogs, including a German shepherd rescue with three legs. She’s big into dog rescue, and volunteers with a dog rescue organization in Rancho Santa Margarita.

By 10:50 a.m., Cogert was writing a report concerning an OIS. She grabbed a sandwich for lunch around noon.

Near the end of her shift, she still was working on reports.

A sign in her office cubicle is a quote from Albert Einstein: “Strive not to be a success but rather to be of value.”

Over the course of her career, Cogert has pretty much seen it all.

Kelli Cogert, a senior forensic specialist at the OC Crime Lab Identification Bureau, uses a flashlight to help find fingerprints on the outside and inside handle of a door whose glass was shattered by a burglar.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Some cases stick out for her.

Cogert got emotional when she recalled a memorable call she worked on, the 1999 murder of Deputy Brad Riches by a gunman in Lake Forest.

“We were friends,” she said.

Cogert also worked on the murder of Samantha Runnion, the 5-year-old whose abduction and death in 2002 made national news.

Such cases underscore the importance of the work Cogert and other CSI specialists perform every day, mostly out of the spotlight.

Said Cogert: “We do this job to catch the bad guys.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge