The woman pulled into the park-and-ride and was alarmed at what she saw:

A dozen or so men, all dressed in military garb, loading suspicious-looking bags into a van.

Terrified, she called her boyfriend, a police officer at an Orange County law enforcement agency.

Was this a terrorist attack in the making?

The officer, who is trained as a Terrorism Liaison Officer (TLO) for his agency, notified the Orange County Intelligence Assessment Center (OCIAC), a vital asset to O.C. that most residents have no clue exists. The OCIAC coordinated with police chiefs, and local FBI and Department of Homeland Security officials were notified.

Anaheim Lt. Brian McElhaney, who at the time was embedded at OCIAC as its director, called a quick plan-of-action meeting. One of McElhaney’s intelligence investigators assigned to OCIAC flipped through a Rolodex of contacts and called an official at Camp Pendleton.

“Hey, are you guys running any terrorism-related training exercises in Orange County right now?” he asked.

Indeed, the intelligence investigator was told, an exercise was being held that moment.

And, in less than half an hour, what had been a heart-pounding threat that would have put all of O.C. and surrounding counties on high alert — panic, even — was dismissed as nothing to be concerned about.

With its information and intelligence-gathering tentacles stretching into numerous local, state and federal sources of information, OCIAC — which this year celebrates its 10th anniversary — is a vital tool in keeping Orange County safe from criminal and terrorist activity.

The fusion center houses representatives from 16 federal, state and local law enforcement and related agencies.

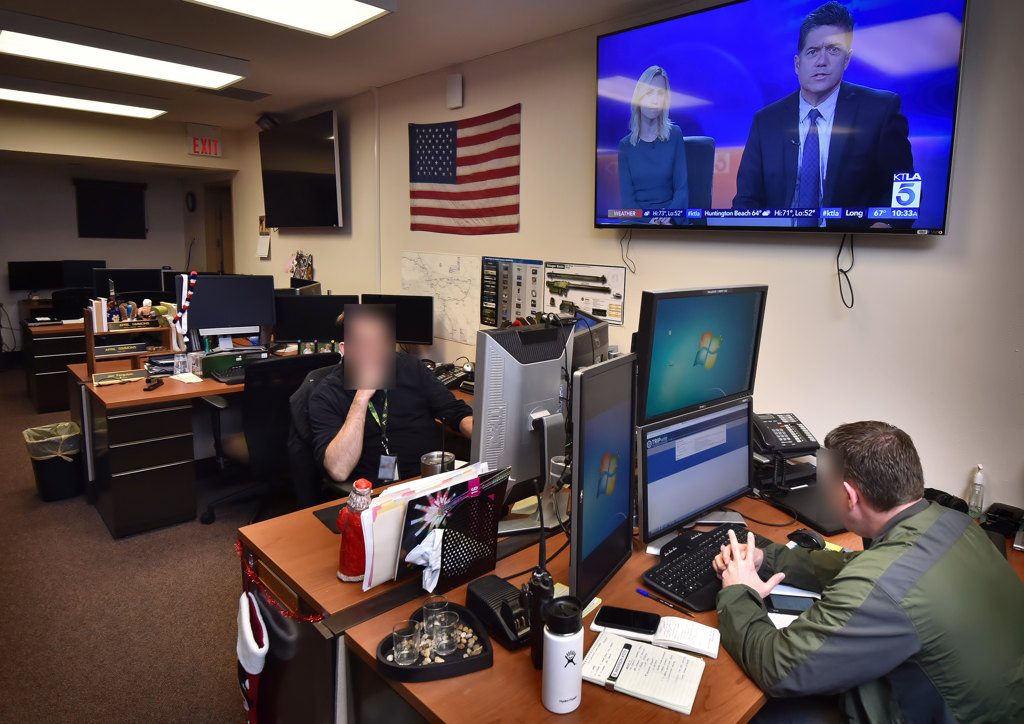

Agents whose identities are obscured work at the Orange County Intelligence Assessment Center (OCIAC).

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

It’s staffed by nearly 45 full-time and part-time employees, including law enforcement and intelligence analysts embedded from agencies including the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, Orange County District Attorney’s Office, the La Habra, Anaheim, Huntington Beach, Orange, Irvine, Laguna Beach, UC Irvine and Garden Grove PDs, and officials representing various divisions from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The fire community serves as a critical partner in the fusion center and has representatives from the Orange County Fire Authority and Anaheim Fire & Rescue. The OCSD has direct responsibility for the overall policy and direction of OCIAC, in close coordination with the Orange County Chiefs and Sheriff’s Association.

OCIAC is a secure facility where, when tours of elected officials, law enforcement and fire officials and other partners come through, employees switch their computers to screen-saver or desktop mode to mask the sensitive information they’re reviewing.

And the facility includes a secure room; only cleared personnel with a classified clearance can enter it. The room allows OCIAC to receive, share and discuss sensitive and classified information with appropriate local, state, federal, and private-sector partners.

A lesson learned following 9/11 was the lack and minimal flow of information between the federal government and local government, and vice versa. Today, the access to information is immediate, and OCIAC serves as that conduit of information-sharing in Orange County.

OCIAC is one of 79 recognized DHS “fusion centers” set up around the country following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 so local, state and federal law enforcement agencies can better receive, collect, analyze, and, more critically, share information.

And the fusion center is making a big difference, says OCSD Lt. Chris Hays, the center’s current director.

“In order for law enforcement agencies to do their job efficiently and effectively in the 20th century, they can’t afford to not have a fusion center,” said Hays, a former Marine sniper who helped set up, in August 2001, the pre-cursor agency to OCIAC, the Terrorism Early Warning Group, which folded in 2007 when OCIAC was formed as a U.S. Department of Homeland Security-recognized fusion center.

“Intelligence-led policing is fairly new, but it’s only going to become more critical,” said Hays, whose business card reads, A safe and secure Orange County and homeland.

At the recent 10th-annual National Fusion Center Association (NFCA) conference awards ceremony held on the East Coast, OCIAC was selected by its peers spanning federal, state, and local agencies to receive three of nine awards: the FBI Terrorist Screening Award (TSC) Partnership, Excellence in the Field of Fusion Center Outreach, and Excellence in the Field of Cyber Protection.

The awards underscore one of the center’s unofficial slogans, memorialized in a Michael Jordan quote hanging on a bulletin board on a wall by Hays’ office:

Talent wins games, but teamwork and intelligence wins championships.

MISCONCEPTION

Hays and his deputy director, a seven-year veteran of OCIAC, say there’s a misconception among some people who’ve heard about OCIAC that it’s some kind of shadowy CIA-run outfit.

In fact, although it’s funded by two federal grants, OCIAC — which has four units in the areas of Critical Infrastructure Protection, Terrorism Liaison Officer/SHIELD (SHIELD works with local businesses to share information), Analysis, and Intelligence — is run by local and state government agencies, and is not investigative in nature.

Its key function is to serve as an information-vetting apparatus. OCIAC vets reports that come in about suspicious activity from law enforcement, fire, public health, and the general public, and — if such activity meets certain national thresholds for behavior indicative of possibly criminal or terrorist behavior, the center routes such information to the FBI, DHS or local law enforcement agencies for further investigation or follow-up.

Last year, more than 1,100 tips/leads of suspicious activity came into OCIAC from the public via its website (click here) or from public safety, health care and private-sector personnel who’ve been, and continue to be, trained to be more vigilant about signs of possible terrorism and criminal activity.

For example, the “See Something, Say Something” campaign in Orange County (KeepOCSafe) is one way OCIAC receives information.

When vetting information, OCIAC follows guidelines established by the nationwide SAR (Suspicious Activity Reporting) Initiative, which lists 16 indicators and examples when it comes to reporting suspicious activities.

Examples include misrepresentation.

In one case mentioned on SAR’s website, a person used a stolen uniform from a private security company to gain access to the video monitoring control room of a shopping mall. Once inside the room, the person was caught trying to identify the locations of surveillance cameras throughout the mall.

Another example is photography.

The SAR website said examples include someone taking pictures or video of infrequently used access points, the superstructure of a bridge, and personnel performing security functions.

Hays pointed out that one of the key missions of OCIAC is ensuring that the civil liberties and privacy interests of American citizens are protected throughout the intelligence process.

If someone merely “looks” suspicious, Hays said, that’s not a crime.

“Is the behavior indicative of criminal or terrorist behavior? That’s the key,” Hays said.

A major focus of OCIAC is cybercrimes. The fusion center helps educate public safety partners about the increasing number of cyber threats and ensuring the information is reported.

“That’s a big challenge and concern for us,” Hays said.

CONNECTING THE DOTS

Analysts and intelligence-gatherers at OCIAC work to identify trends from the information they receive. OCIAC coordinates with federal partners to identify the national and international trends to determine their impact on the regional and local level.

In 2015, OCIAC played a significant role in the conviction by the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) of two Anaheim men for planning to join ISIS, Hays said. The following year, Muhanad Badawi, 24, and Nader Elhuzayel, 24, were convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

“It’s a never-ending connection of dots,” Hays said of working to prevent terrorist and other criminal activity. “The reality of terrorism in Orange County is a lot bigger than the residents of Orange County recognize.”

One recent criminal case further illustrates the role OCIAC plays in keeping O.C. safe.

The Nov. 2 arrest of David Kenneth Smith, of Los Angeles, began days earlier with a suspicious activity report from a teacher at Soka University, in Aliso Viejo, about a former student sending her threatening emails. Another anonymous report of suspicious activity linked to Smith came in from OC Crime Stoppers.

OCIAC investigators discovered disturbing videos on YouTube of Smith threatening to go on a killing spree.

Smith apparently had become angered by a punishment he received at the university for marijuana use in 2008, according to an OCSD news release.

When authorities arrested Smith, they found several loaded rifles and shotguns inside his home.

Smith, who graduated from Soka University in 2008, has been charged with one felony count of making criminal threats. He is awaiting a court hearing and remains in custody on $1 million bail.

“This case is a great example of connecting the dots,” Hays said. “We were able to help put all the pieces together (and get Smith arrested).”

MORE FUNDING IS CRITICAL

Hays says OCIAC needs more staffing, and added that if federal grant funding of the center ever dries up, it would be critical for the county and city government to step up to keep OCIAC operating.

He said that in addition to assessing information that comes into the center, OCIAC plays the important role of conducting risk assessments to critical infrastructure partners, government buildings, faith-based facilities, and other properties.

For example, following the Nov. 5, 2017 mass shooting at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas that claimed the lives of 26 parishioners, the OCIAC immediately coordinated with two of O.C.’s largest churches to host and plan a faith-based symposium in 2018 to provide education and training to assist all-faiths protecting their facility.

“We do the same with schools, hotels, hospitals, clinics, and private-sector businesses,” Hays said.

What’s more, working for OCIAC is a priceless experience for a law enforcement officer, McElhaney said.

“When you sign up to be a police officer, you might someday hope to be on SWAT or the K9 unit, but you don’t expect to become a member of the intelligence community, let alone run a fusion center,” said McElhaney, director of OCIAC for 2½ years, from 2011 to 2014.

“It was the opportunity of a lifetime,” McElhaney said. “I have much love for the people in the intelligence community.”

Hays said OCIAC has gotten a lot better each year keeping O.C. safe.

“We’ve had 10 years to figure it out,” he said. “The heart of this operation is truly all the individuals and their laptops and their iPads and their iPhones. Even though we have this building where we all come together Monday through Friday, they work 24 hours a day, seven days a week, from their homes, their cars — everywhere.

“The heart of OCIAC is its people. We can be anywhere doing what we do.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge