When Officer Ronnie Reyes underwent over 150 hours of schooling in preparation for becoming a Garden Grove Police Department motor officer, one thing was perfectly clear:

This was no “CHiPs.”

“I think Ponch and Jon had it pretty easy,” says Reyes, in reference to the late ’70s/early ’80s TV series following two fictional California Highway Patrol motorcycle officers.

The training involved in preparing officers to work on motorcycles in the department’s traffic unit tests officers physically, emotionally and mentally in order to get them ready for the real-life situations they’ll face.

And for Reyes, it was even more of a challenge considering he’d never ridden a motorcycle before.

“Your head and eye placement is so important because if you’re not looking in the right direction, you’re gonna fall,” says Reyes. “And me not having any experience before, I fell a lot.”

But he, like those from other agencies that were part of the two-week, 80-hour motor school in San Bernardino that officers must pass to become motorcycle cops, just kept getting back up again.

Tough training

Before even getting to motor school, officers must take a series of classes involving important materials like field sobriety testing, Advanced Roadside Impairment Driving, Lidar/Radar certification (speed tracking) and drug recognition (Reyes is a certified Drug Recognition Expert), as well as start learning to ride on the motorcycle.

“My partner [Paul Ashby] … we did those classes together. It was helpful to have somebody going through this whole process with you,” Reyes says. “At first it was something simple like, you’re riding around the parking lot of the station. Then you’re gonna go around the block. Then today we’re gonna go to Anaheim Stadium so we can start practicing on these cone patterns.”

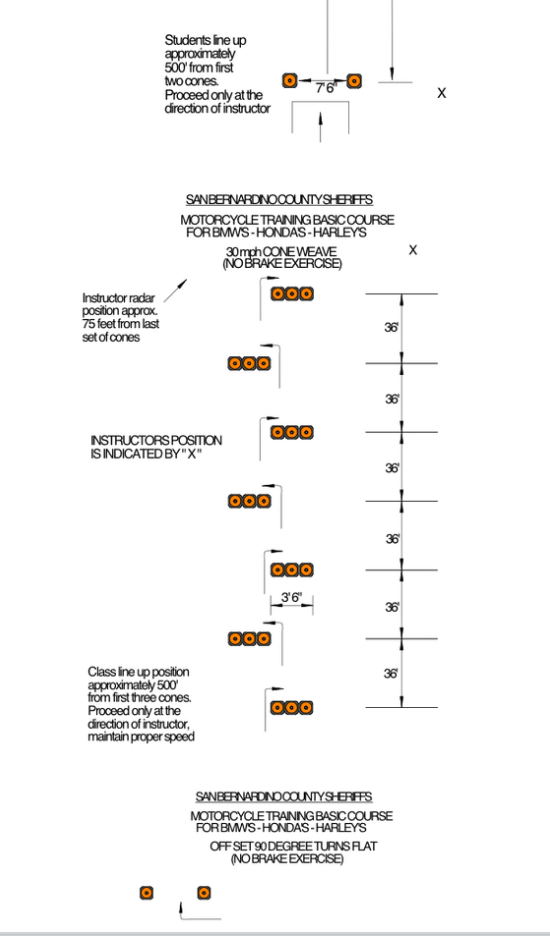

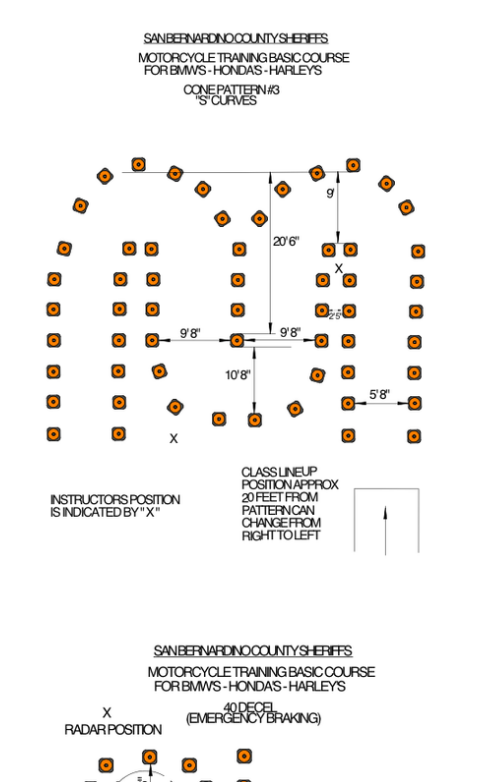

The first week of motor school involves intense patterns practice, grading and testing. The patterns are set up with cones that officers must maneuver through without touching. Instructors grade the officers based not only on avoiding the cones but on proper hand and eye placement and other factors. There are 10 patterns and four that officers are tested on after the first week of training and grading.

“If you’re in a pattern and you drop the bike, you crash or you fall off the bike … the whole day, you get a 1 [lowest grade]because you drop the bike,” says Reyes. “You’re graded every day for all 10 of these patterns.”

Patterns include ominous-sounding titles like The Eliminator – which looks like s-curves – in which riders must maintain a very low speed of between 1 and 2 mph without braking and while giving it throttle (aka “feathering the clutch”). Officers must make it through this pattern three times in one direction and then three more times in another direction in a row. They get 10 tries. If there is an error, the officer must start all over. Not an easy task on a 900-pound machine.

“Literally you’re trying to balance and give it enough throttle,” he says. “The stuff that we’re doing on these bikes, it’s unbelievable.”

Then there’s The 180 Decel, where officers must get their bikes up to 30 mph at a specific cone, then brake fast enough to where they’re downshifting, then go 1-2 mph, then make turns on very sharp angles. The 30 mph Cone Weave has officers get their bikes to 30 mph at a certain point, maintaining that exactly while weaving in and out of a series of cones.

“If you hit a cone, you fail that,” Reyes says.

Officers also had to perform the 40 Decel, an emergency braking exercise to prepare them in accident avoidance. It simulates riding 40 mph down a street and having to downshift to 1-2 mph rapidly to prevent a collision.

An example of a pattern exercise that must be mastered as part of the 80-hour motor school in San Bernardino.

For warm-up, officers would perform figure eights, circle patterns in tight spaces and follow the leader, in which they followed the person in front of them going 2-3 mph in and out of hundreds of cones and around poles and other tight spaces.

“You’re basically having to squeeze the clutch nonstop and you’re giving it throttle nonstop,” he says. “Your hands are just dying.”

Long rides

After getting through the first week, officers who pass – and not everyone does – go on to week two, which involves street riding and long rides, including a 250-mile nearly nonstop ride from San Bernardino, through Lake Elsinore, Dana Point, along Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, San Pedro, Palos Verdes, Los Angeles and back to San Bernardino.

“They’re basically teaching you when you’re fatigued and you’re tired, your body can still do it … and you got to prepare yourself mentally,” he says. “It’s pretty cool because the public sees you and are cheering for you and are taking pictures. When you’re riding, a lot of people are waving and honking.”

Another day they rode 200 miles up to Big Bear and Lake Arrowhead and to Cook’s Corner.

“They teach you how to go through the canyon riding and be safe,” he says.

Another aspect of the training is riding on dirt roads, sand, gravel, up and down hills, and through brush and tumbleweed. Officers also practice scenarios where they ride up to a scene, get off the bike and shoot a target. They also train in vehicle pursuits and traffic stops.

“If, for example, you’re chasing somebody in a pursuit and the guy all of a sudden jumps out of the car and you’re in a foot chase, you have to be comfortable and confident in riding the bike in an area that is not meant for riding a bike,” he says.

Officers who pass the second week then are officially considered motor officers and are awarded a Certificate of Completion from the San Bernardino Motor School Academy.

“It’s physically stressful, it’s emotionally stressful,” says Reyes about motor school. “It’s difficult on the body, on the mind – but quitting wasn’t an option.”

For that reason, he says when injuries would occur from falling off a bike – and they would – officers often just toughed it out limping their way through, rather than starting all over.

Life on a bike

Now riding along on his custom-made seat (at 5 feet, 4 inches, Reyes wasn’t able to comfortably rest his feet on the ground from the particularly high BMW motorcycle, so he found someone to make a special seat), he feels more at home on the bike every day.

Since completing motor school in March, he heeds the advice of his mentors (among them are motor school instructors Royce Wimmer and Kathy Anderson, whom he is grateful for) to keep practicing and stay humble.

“People say when you become a motor officer, the odds of you crashing between the first three and six months is pretty high,” he says.

At the same time, he is enjoying himself and feeling useful being able to respond to an incident much quicker than when he was in a car on patrol – despite the 30 pounds of gear around his waist, having to wear a vest and helmet, riding in the hot sun all day and having a strange-looking forearm tan.

“You have certain goals in your career, and it was just something that I had a strong interest in for some time,” he says. “I wanted to challenge myself and thankfully, I was able to pass and do it.”

Officer Ronnie Reyes had never ridden a motorcycle before he signed up to train to become a GGPD motor officer.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge