It used to be that members of the Orange PD’s Crisis Negotiations Unit (CNU) maybe were dispatched to one or two calls a year.

For some reason or a combination of reasons — drugs, mental health issues, economic woes — things have picked up in recent years, with the eight-person team now averaging a half-dozen or so responses a year, according to Team Leader Sgt. Phil McMullin.

So far in 2017, the CNU has been dispatched to four calls. The specially trained officers work out of the front of a SWAT vehicle. During negotiations, the compartment is sealed off to prevent distractions as they work phones and computers in the hopes of diffusing potential powder-keg situations.

Each callout puts to the test the well-honed skills required of CNU members, who after 40 hours of training put themselves in harrowing situations in which someone’s life hangs in the balance, and where doing or saying the wrong thing can, in seconds, contribute to things going south.

Orange PD’s Crisis Negotiations Unit Assistant Team Leaders Det. Tina Dunneback and Officer Dan Norman demonstrate the capabilities of OPD’s SWAT/CNU truck.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

With some calls lasting several hours, CNU members have to be endurance fiends, sometimes even foregoing bathroom breaks to prevent the barricaded gunman on the other end of the phone line, or the depressed teen teetering on a building’s ledge, from ending it all.

“It isn’t for everyone,” said OPD economic crimes Det. Tina Dunneback, a CNU member for 16 years. “You have to be genuine and truly care. I’m not saying other cops don’t care, but (being a negotiator) means you need to be genuine, empathetic and sympathetic. A subject or suspect will easily pick up on it if you’re not.”

Dunneback is an assistant team leader on the CNU, along with Officer Dan Norman.

Under the direction of McMullin, they lead a team whose other members are negotiators Det. Julie Taketa, Cpl. Walt Bueno, Inv. MD King, Cpl. Guillermo “Memo” Betancourt, and Cpl. Lucia Zvonaru.

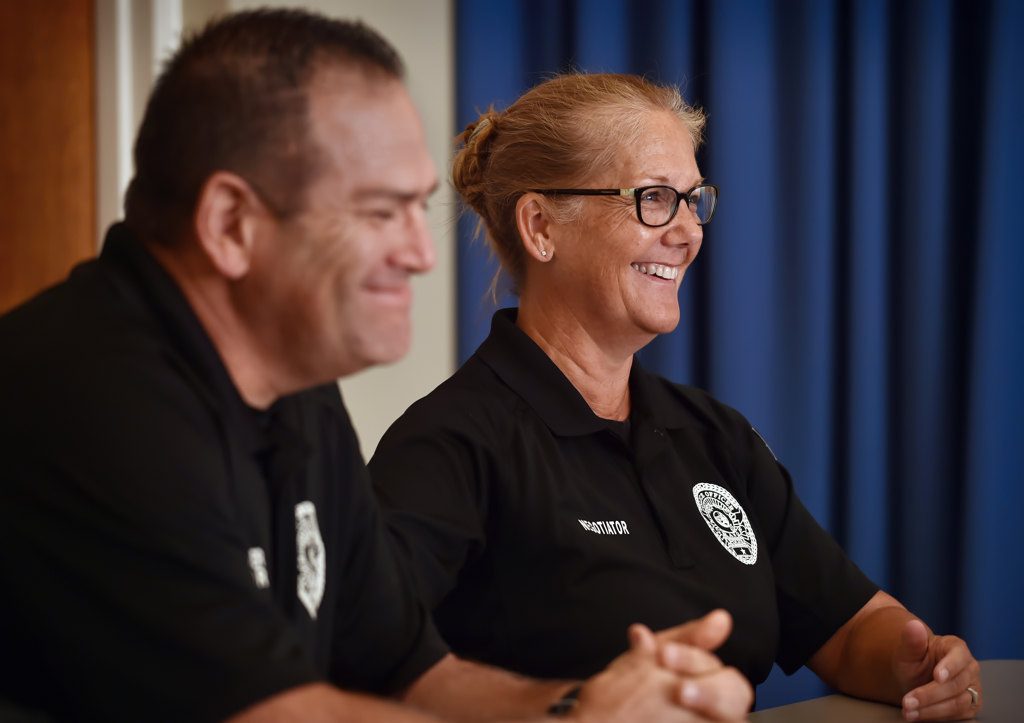

Orange PD’s SWAT Crisis Negotiations Unit Assistant Team Leaders Officer Dan Norman and Tina Dunneback talk about their experiences with the CNU team.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“I know what my strengths are,” King, the newest member of the unit with about a year of experience, said when asked why he wanted to be a crisis negotiator. “Being out in the field a lot, I’ve learned how to talk to people and assess situations. I think I’m pretty good at it.”

King and Bueno recently were called out to negotiate with an armed subject who was having relationship issues. The CNU always sends a minimum of two officers out, and ideally four.

Fortunately, it took only two minutes for King and Bueno to talk the barricaded man into peacefully surrendering.

Typically, calls involving the CNU unit, which is attached to the OPD SWAT team, last much longer.

In April, Norman was the primary negotiator on a call involving a suicidal suspect who barricaded himself in a room at a school.

The call highlights the specialized craft of CNU members, who need to have an ability to listen, to make a connection and establish rapport with the subject, and to follow a cardinal rule: Never lie, and never make a promise you can’t keep.

Orange PD’s Crisis Negotiations Unit Assistant Team Leaders Det. Tina Dunneback and Officer Dan Norman go through OPD’s SWAT/CNU truck.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“You want to find a common ground, or what we call a ‘hook,’” Dunneback explains. “What are we going to talk about that will get them to respond to us?”

CNU members also need to identify who might be useful for the subject to hear from, and who might set him or her off — for example, a relative he or she doesn’t like.

Officer Dan Norman, assistant team leader for Orange PD’s Crisis Negotiations Unit.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Norman was the primary negotiator on the high school call, and Dunneback was the secondary negotiator.

The role of the primary negotiator is to talk with a subject, while the secondary negotiator acts as something of a coach, listening intently to both the subject and the primary negotiator and sometimes slipping notes or bending an ear with suggestions and advice.

MD King, an investigator with OPD’s gang unit and one of the negotiators for Orange PD’s Crisis Negotiations Unit.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Another negotiator acts as a scribe, writing everything down, such as when the officer and subject communicate and when they don’t.

Another negotiator gathers information about the subject and his family, co-workers, friends — anything he or she can find out.

Norman’s goal, as it is on all CNU calls, was to build a relationship with the suicidal man and get him to trust him.

Norman started by introducing himself.

“I’m Dan,” he said. “What’s going on today?”

Norman followed by asking the man to come out of the room so the two could talk face to face.

“Sometimes,” McMullin said, “(subjects) are just waiting for the invitation, and that’s all they need to hear to surrender.”

Orange PD’s SWAT Crisis Negotiations Unit Assistant Team Leaders Officer Dan Norman and Det. Tina Dunneback talk about the satisfaction they get by being on the CNU team.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

The invite didn’t work on the suspect.

So Norman got to work, searching for a hook.

McMullin stressed that the goal on all CNU calls is to negotiate a safe resolution, not solve the underlying problem.

“We’re not doctors who are going to fix someone for life,” McMullin said.

Norman engaged the suspect in deep conversations about his job.

“I wound up asking him a lot about his job and what he did,” Norman said. “At points, I had to challenge him — ‘Hey, you need to come out right now and talk face to face’ — but he wouldn’t come out.”

Norman and the suspect covered many other subjects over the course of their six-hour telephone conversation. Norman and his partners also played for the suspect a recorded message from a friend.

Officer Dan Norman, assistant team leader for Orange PD’s Crisis Negotiations Unit, stands in front of a door that remains closed in the SWAT/CNU truck when actual negotiations are going on.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Unlike as portrayed in movies and on TV shows, negotiators rarely let a third party talk live to a subject. What they say off the cuff could unwittingly trigger a tragedy, such as the subject killing himself so the person on the other end of the phone can hear the horrific act.

Eventually, at 8:35 p.m., after a near 10-hour standoff, the incident was peacefully resolved.

“He knew the SWAT team was out there and they had plans to come in,” Norman said. “I told him, ‘They’re going to come in, and I want you to be safe.’”

After the school call, Norman, understandably, was drained.

“I never had an interest in joining the actual SWAT team,” Norman said, “but I always knew I had the skills to talk to someone and negotiate with them.”

People threatening suicide account for about 80 percent of the CNU’s calls, followed by a barricaded subject, such as an incident this year when a man armed with a knife barricaded himself in an apartment on South Lemon Street, a call that lasted 12 hours before it ended with the man being taken into custody.

Hostage-situation calls are the most rare for the CNU.

When negotiating, CNU members use a telephone (if a subject doesn’t have a cell phone or landline, officers will toss him or her a “throw phone”), talk face to face, use a bullhorn or P.A. system, and even use social media and texting.

Dunneback recalls an annoyed subject who got tired of her commands on a bullhorn.

The subject texted:

Shut her up, I’m tired of listening to her.

The call ended peacefully.

“It’s a good feeling when it works,” she said.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge