Editor’s note: Michael Streed is a retired Orange Police sergeant, owner of SketchCop Solutions and author of the book, “SketchCop: Drawing a Line Against Crime.” You can get his book here. Behind the Badge periodically will share excerpts from his book.

“Attention all units and stations, for Station 18, a 207 from the Stanton area … the child is described as a female, white, 5 years old…”

The crime broadcast at approximately 5:30 p.m. on July 15, 2002, sent chills down my spine. The Orange County Sheriff’s Department had initiated a countywide emergency police radio broadcast about a child who had been kidnapped from one of the areas where they provided police services.

After already spending many years in law enforcement, I was conditioned to focus only on “select” countywide emergency broadcasts. Those I paid the most attention to were those crimes occurring closest to my city. The others were nothing more than white noise.

But cases where a child’s been stolen by a stranger? That’s a whole different ballgame. Before the last word in the broadcast is spoken an adrenaline surge kicks in, and suddenly you’re running on all cylinders. In that instance, your total focus is on each word the dispatcher is speaking.

On the evening of the reported child abduction, I was working a uniformed patrol shift for the Orange Police Department. I was assigned to train a recent academy graduate, a police trainee. I remember feeling helpless as he chauffeured us around the city, listening to the emergency radio broadcast that was repeated several times over the next couple of hours. You could tell even the dispatchers were feeling the pressure, as the urgency in the sound of their voices grew with each new broadcast.

At the time of the kidnapping, I had worked closely with many Orange County Sheriff’s Department detectives. As both a law enforcement professional and police sketch artist, I enjoyed assisting them with several sexual assault and homicide cases. But I sensed that this case would be different than the rest, so I commented to my partner that we should probably catch up on our work at headquarters, as they would soon be calling and I would have to leave.

I was confident that, if detectives had a good witness, they would call and ask me to assist with a composite sketch. Again, based upon the circumstances and gravity of the case, I knew that it was just a matter of time. The case dynamics would demand my full attention for sure because, from what the broadcast said, this was a stranger kidnapping of a child. In my experience as a parent and as a law enforcement professional, this is the worst kind of crime imaginable. So I waited, but the call never came.

Halfway into our shift, the emergency broadcasts began to taper off. So, to take my mind off of what happened, I distracted myself by becoming immersed in my own activity.

Yet despite how many radio calls we handled throughout the night, the little girl who would soon become known to the world as “Samantha” occupied my thoughts throughout the remainder of my shift.

The pressure I began to feel was tremendous. I had no doubt that I was up for the task because I had been in such situations before. It’s just a lot to think about when you know that the case hinges on your sketch.

Earlier in my career, I’d experienced two other profile stranger abduction cases involving child victims. Both cases relied heavily on composite sketches at the outset, and the facts of each case presented unique challenges.

The first incident occurred in 1983, when I was asked to assist the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department in their search for Laura Bradbury, a 3-year-old girl from Huntington Beach. Laura had been camping with her family at Joshua Tree National Park. She disappeared after going to a bathroom with her 8-year-old brother and was reported missing by her family.

During their investigation, sheriff’s detectives developed a witness who reported seeing Laura with an unknown adult male. Later, this witness described to me a bearded, scraggly stranger. The resulting sketch provided detectives with their first real clue to what might have happened to Laura.

Unfortunately, the sketch didn’t lead to any suspects. What followed, though, was an intensive and exhaustive investigation. It wasn’t until years later that authorities found what they believed to be evidence of human body parts that they believed belonged to Laura.

At this writing, no suspects have been located and no arrests made.

My other stranger-abduction case experience came in 1997 with the kidnapping and murder of 10-year-old Anthony Martinez, a case that I detailed in a previous chapter.

Both of these cases were difficult because the witnesses were severely traumatized or didn’t see anything. Stranger abduction cases always demand quick action because time can become your worst enemy. The Orange County Sheriff’s Department was already on the right track when they immediately broadcast valuable information to law enforcement about Samantha’s abduction.

In any criminal investigation, especially cases like these, a good witness is golden. One can often make a difference in bringing the kidnapped child back safe, or if the unthinkable happens, helping bring the suspect to justice…

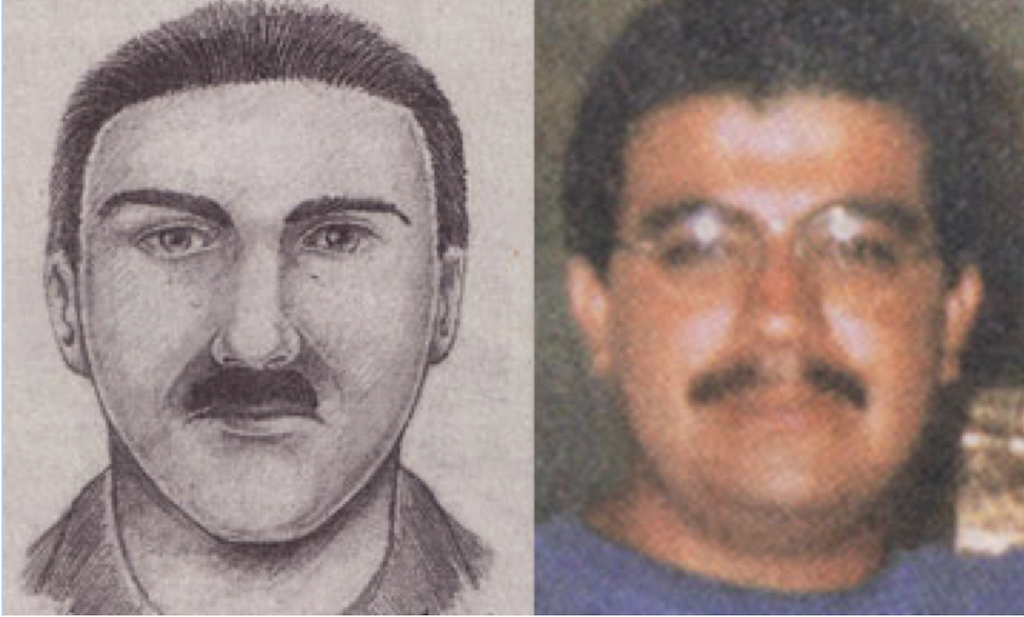

Editor’s note: Below is the sketch that Streed created with the help of a 5-year-old witness. The suspect was arrested and convicted of murder in the tragic 2002 killing of Samantha Runnion. He was sentenced to death. The first of the state’s two mandatory appeals for the death penalty sentence has been denied, appealed and upheld. The second appeal will probably be filed around the 20th anniversary of Samantha’s death. “I am satisfied so long as he can’t hurt anyone else,” says Samantha’s mother, Erin Runnion, founder of The Joyful Child Foundation (thejoyfulchild.org), which is dedicated to preventing crimes against children through programs that educate, empower and unite families and communities. One way the non-profit does this is through BRAVE, an interactive life-skills program designed to promote health, personal safety, and resilience skills for students in preschool through the 12th grade. The Westminster School District recently voted to implement BRAVE district wide over the course of the next three years.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge