The OC Crime Lab’s trace analysts focus on the details – the minute details, that is.

Things like paint chips, hair, fibers, lightbulb filaments, and other microscopic evidence.

Forensic Scientists Linda Huber, Don Petka, and Prudence Britton are the Orange County Sheriff’s Department’s three trace analysts, working under Assistant Director Joseph Jaing and Trace Supervisor Curtis Heye.

The trace department receives a wide range of evidence for analysis. Often, they’re looking to link a piece of evidence from a crime scene to evidence found with a suspect.

Forensic Scientist Prudence Britton with a poster detailing the different types of evidence the OC Crime Lab scientists typically analyze.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“Forensic science is based on Locard’s exchange principle, which says whenever someone goes somewhere they’re going to leave something behind and they’re also going to take something with them,” Britton explained. “If we can find that something from the crime scene and make the association with the suspect or with a particular item, it could support witness statements, it could support the investigators, what they’ve already determined from other evidence.”

“The more associations that you have, the stronger that the case is going to be,” she said.

In lucky instances, the association is as obvious as a piece of duct tape ripped from a roll found at a suspect’s house used to bind a victim or on an explosive device. Matching the two can be like fitting together pieces of a puzzle.

“There may be that physical match between the end of the tape and the tape that was used at the crime scene,” Britton said. “In that case, we could say with certainty that that tape was used at that crime scene.”

In another case, analysts used a lightbox with polarizing filters to discover a pattern in the plastic of a set of Ziploc bags, called retardation colors, created during manufacturing. The OC Crime Lab used the pattern to sequence a bag connected to a crime with other bags found in a box at the suspect’s house.

“Sometimes you get these different cases, and it may only be a once in a lifetime,” Britton said. “But you never know when that type of thing is going to show up again.”

The scientists use visual examinations, microscopes, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (for organic samples such as tape or fibers), a scanning electron microscope with an energy-dispersive x-ray detector (which creates images using electrons, giving a very high magnification), and more to assess evidence.

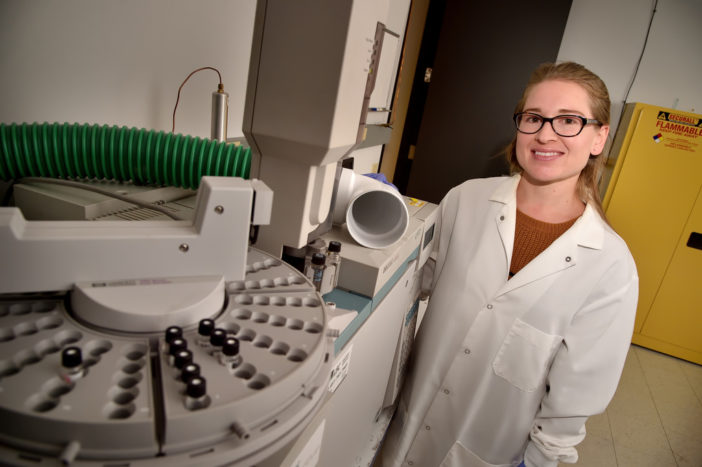

Universal reference standards liquids are used to help identify evidence samples at the OC Crime Lab.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Britton, the newest team member, focuses mostly on fire debris analysis. Using a gas chromatograph (similar to the instruments that examine blood alcohol and drug levels) she proves the existence of ignitable liquids such as gasoline or diesel at a crime scene.

Britton, Huber, and Petka carefully examine the printouts, which look something like a heart monitor reading. They look for recognizable patterns in the peaks – the “three musketeers,” the “castle group” of five that looks remotely like a Disney castle, or the “gang of four.”

“So long as they have these identifying patterns we are able to make the identification,” Britton said. “Most commonly the ignitable liquid we get in our samples is gasoline because it’s so readily available, everyone has access to it, and it’s cheap as well.”

When the patterns are not easily recognizable, the OC Crime Lab turns to its reference collection of more than 700 samples to accurately identify the flammable substance.

One common analysis is fiber. Britton says the OC Crime Lab is able to identify the type, such as cotton, nylon, or polyester, as well as other characteristics that allow the scientists to determine whether the fiber likely came from a wig, carpet, or other use, and can lead to an association between a suspect and crime scene.

A less-common analysis, done by Petka, is discovering whether filament in non-LED headlights had a brittle break (the headlights were off) or has melted glass stuck to it (the headlights were on) proves or disproves a suspect’s story.

“Maybe one driver says the car was coming towards me, they didn’t have their headlights on, that’s why we collided,” Britton said. “Looking under the microscope… if the headlamp was on that metal would be really hot, so when the collision occurred, it would have distorted and the glass from the headlamp that’s breaking melts to that hot filament.”

At the OC Crime Lab with Forensic Scientist Prudence Britton.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Britton, who has a forensic science in applied chemistry degree from the University of Technology in Sydney, wanted to be a detective as a child. She enjoyed reading crime novels about crime solvers such as Sherlock Holmes.

But in school she became more interested in science classes, particularly chemistry.

“I thought, how can I combine the crime type of a job with the science that I really enjoy,” Britton recalled. “So, I started to pursue forensic science.”

She started at the Orange County Sheriff’s Department in 2013 as a forensic technician working in DNA, and shortly thereafter moved into forensic alcohol, reviewing DUI and post-mortem samples for presence of alcohol. In 2014, a job opened in trace analysis and Britton moved into her current position.

“It seemed interesting because of the variety of different evidence that we get to analyze here,” she said.

Though she doesn’t often hear the outcome of her cases, for Britton – as for many in law enforcement – the most important part is being able to help people.

“It’s just important for the victims and their families to know that there’s someone doing their best to try and get answers for what happened in these circumstances,” she said. “There’s terrible things that happen and unfortunately nothing is ever going to be able to change that, but hopefully, maybe, we can get some closure for some of the victims and their families.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge