A flash bang triggers a concussion of sound and energy out a warehouse door and into the parking lot. A car alarm instantly cries out.

Joshua Bobko is hanging back, carefully watching the West County SWAT team pour through the doorway of an empty Fountain Valley warehouse. The threat is a training simulation but Bobko’s concern is real. And the car alarm, of course, just keeps going.

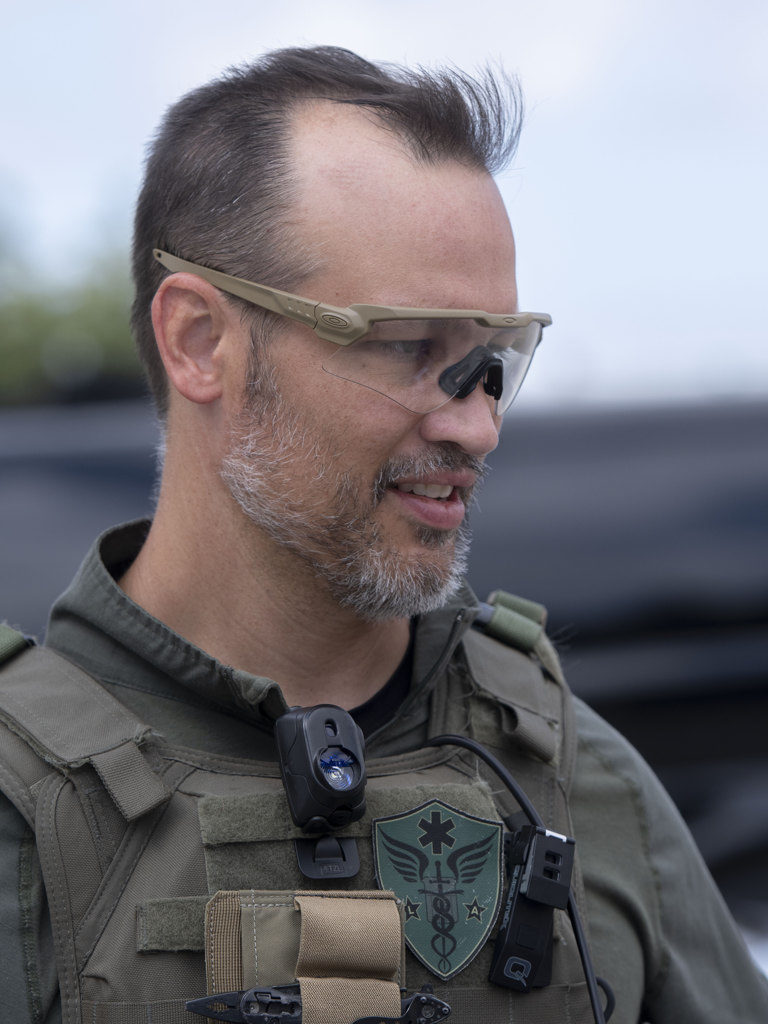

Dr. Joshua Bobko taking part in a training exercise with West (Orange) County SWAT in Fountain Valley on Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2019. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

“That one second of unknown is crazy,” he says a few steps outside the door, dressed in tactical gear, including a weapon and protective vest. He’s the team’s medic and advisor, and he’s undergone tactical training.

Bobko is an Air Force veteran and full-time E.R. doctor, so he’s seen his share of bad. He knows how even the simple and simulated can sometimes go wrong. His job is to worry and he’s happy to take on that responsibility.

“You’re worried when they tap on the door, the whole house might explode,” Bobko says. “I have the easy job. These guys are gonna go, bomb or no bomb?”

He worked the previous night in the E.R. but his commitment does not waver. Nothing will keep him from this.

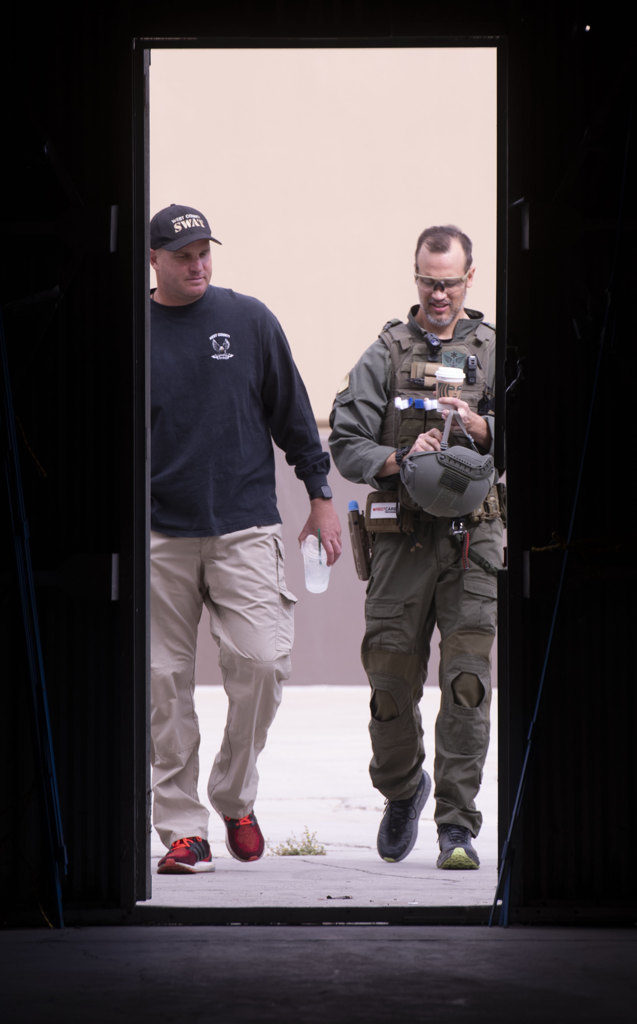

Dr. Joshua Bobko, right, walks back into a warehouse where West (Orange) County SWAT was holding a training exercise in Fountain Valley on Wednesday, October 16, 2019. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

“I’m den mother and I don’t want anybody else touching my guys. If anything ever happened to them and I wasn’t there, I don’t know what I’d do with myself.”

Bobko has, in a way, courted nightmare scenarios for a long time, and consequently became an expert on prepping for them. That’s what makes him so essential to his SWAT team.

He did disaster management when his North Carolina Air Force base was flooded. “I got interested in disaster medicine,” he says. He left the military for medical school and during his residency, was asked to train with the Navy team he worked with.

“Next thing I know, I’m in a field at three in the morning with a bunch of SEALs,” he says.

Dr. Joshua Bobko, center, stands by as West (Orange) County SWAT team members get ready to enter a warehouse in Fountain Valley on Thursday, Oct. 17, 2019 during a training exercise. Bobko is medical director for West County SWAT as well as a reserve at Westminster Police Department. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

During his fellowship at Loma Linda University Medical Center, he worked with local air rescue and FBI special agents and was eventually invited to be a reserve officer for the Westminster PD. providing he entered the academy.

“I did all the things I would have done had I walked in off the street. I just walked in with a different skill set,” he says. “I am a reserve police officer. I can speak police officer. I can move police officer. I can cut my hair short and look police officer, but I make no mistake that these guys do this job all day, every day. Even though I have the training, I do medicine and I would never jump into other roles. It’s just that I can do my job in the context of this mechanism.”

West (Orange) County SWAT team members search for a suspect during a training exercise in Fountain Valley on Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2019. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

The job, Bobko says, is 90 percent team health. He is committed to ensuring health and safety is a priority.

“It’s making sure the guys are able to do the job the team needs them to do. Making sure that thing they don’t want to tell their chain of command about, we’ve taken a look at and it’s not going to cause a problem down the road. Because they’re not going to say no. I have to pull them out to make sure they don’t hurt themselves. I have to say no.”

Next is education.

Dr. Joshua Bobko is a medical SWAT officer with West (Orange) County SWAT. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

“Because it’s going to take me a while to get from the perimeter to their location,” he says. “Making sure they understand the principles of trauma so they don’t forget what is tactically sound because of some medical thing they’re now under stress trying to remember. I want them to stay safe, take care of the problem and each other. Then we’ll deal with the rest of it.

“I watch them and that helps me communicate with them from a point of understanding,” he says. “If I look at how they’re working on some contingency where somebody’s hurt, I can talk to them about their angles. ‘Don’t do your medical treatment here. Take three steps to the left and do your medical treatment there and that maintains your cover.’ Those are things that directly affect them, and you train and train and train until you can’t get it wrong.”

Lastly, it’s actually treating injuries and medical situations at the scene. “The little injuries,” he says. “Whenever we break something, somebody gets cut, or if one of these sim rounds will ricochet.”

Dr. Joshua Bobko stands by during a training exercise for West (Orange) County SWAT in Fountain Valley on Thursday, Oct. 17, 2019. In addition to being the medical director for SWAT, Bobko is an emergency room doctor. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

As much as he brings to this job, he also gets a lot in return.

“I know I lessen their burden a little bit and that’s really cool,” he says. “There’s not a lot of other jobs you can do that affect people so directly just by being there.”

The requisite passion and adrenaline rush of disaster medicine is always tempered by a sobering reality for Bobko, as it would be for any doctor in the job.

“All trauma medicine is predicated on minutes,” he says. “The only thing I can’t give you back is time. I can put blood back in you, but your blood is better than anything I can give you, so the few seconds or few minutes of you not bleeding and your system staying intact is better than an hour of transfusions.”

West (Orange) County SWAT officers run through a training exercise in Fountain Valley on Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2019. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

And the non-profit educational program he co-founded, firstcareprovider.org, has only furthered what the SWAT team already knows: That prepping for a crisis can lessen its impact. Nevertheless, Bobko is resolute.

“It’s the best job there is. We’re the best part of everybody else’s job. Any surgery, any trauma, any heart attack, any birth, anything. The best part of it comes to me and then I’ll call you when I need you. Every shift there’s always something to learn. Something you haven’t seen. Something you didn’t expect.”

Even if the worrying part of the job is never far. Including today.

Dr. Joshua Bobko, right, talks with West (Orange) County SWAT supervisors during a training exercise in Fountain Valley on Thursday, Oct. 17, 2019. In addition to being an ER doctor, Bobko is also medical director for West (Orange) County SWAT. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

“When you do operations, you have that moment when you switch off that laser focus you had,” he says as the team finishes their simulation. “You come back and you’re unloading your weapon or whatever and you let your guard down just a second.”

The team loads up without incident and cars begin to pull out of the parking lot. The car alarm has long since gone quiet. Soon, only Bobko’s car remains.

“I’m always the last person to leave,” he says. “I don’t feel good until everybody is driving home safely. The rest of it, these guys are professional, they can handle anything.”

Dr. Joshua Bobko, right, medical director for West (Orange) County SWAT, stands by as SWAT team members wait to begin a training exercise in Fountain Valley on Thursday, Oct. 17, 2019. (Photo by Paul Rodriguez)

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge