It’s the worst kind of call, but this time the detectives had something more to offer than condolences and an empathetic apology.

On a Friday morning in February, Tustin PD detectives responded to a call of an infant girl found dead in her bassinet.

The baby — one of triplets — was born at just a little more than a pound and had struggled with health issues since her birth months earlier.

Three days after first meeting the family, detectives Pam Hardacre and Tommy Lomeli returned to the family’s apartment.

Hardacre brought with her a mint green box that had been donated to the police department and made for families dealing with such a loss.

“You have to make contact with these parents and here you are intruding on their lives in a really tough situation, but they were just so sweet,” she said. “They were grateful.”

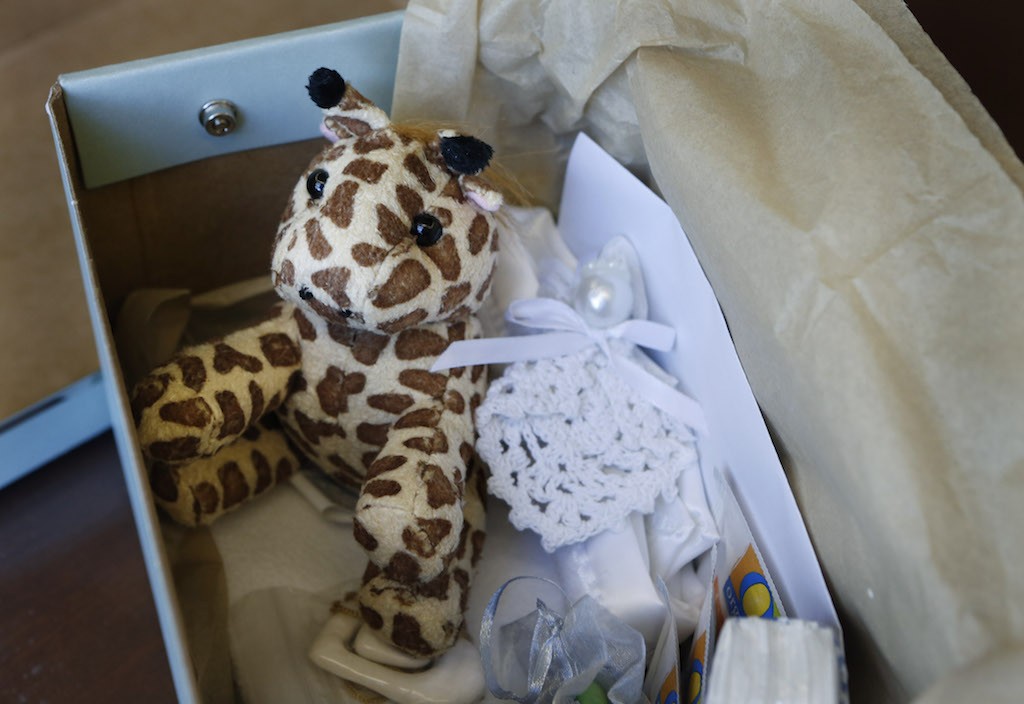

Inside the box was a handmade blanket, Kleenex, a candle and a small stuffed toy. A white crocheted angel ornament and chamomile tea also were settled in the tissue paper.

A pair of ceramic hearts with a hole in the corner were tokens for the grieving parents to carry with them as a reminder of the space in their hearts that will never be filled.

There also was a necklace with two cream-colored ceramic hearts — a small one nestled inside a larger one. The parents were to keep the larger heart and bury the small one with their child to keep a connection with their baby girl.

Every item was so well thought out.

It was as if whoever selected the contents of the box knew exactly what the family was going through.

Last and only

Jose and Catherine Avila had decided their 3-year-old, Milena, would be their last, and only, child.

Catherine endured pre-term labor with her first-born, Jimmy.

Born four months early, Jimmy died from pneumonia in December 2006 after a month-long stay in the neonatal intensive care unit.

The following year, Catherine learned she was pregnant with her daughter, Milena — a pregnancy more difficult than her first.

She stayed on hospital bed rest for four months until Milena was born eight weeks before her due date.

“We had decided we weren’t going to have any more kids,” Catherine said. “It was just too hard with what I had to go through (during pregnancy).”

Three-year-old Milena Avila holds a bunch of sticks she collected at the park. Photo courtesy the Avila family.

Milena was a spunky toddler-going-on-teenager with caramel-colored hair and deep blue eyes.

She only liked to wear dresses, and her hobby-of-the-moment at age 3 was collecting as many sticks from the park that she could wrap her little hands around, proudly passing them off to her father.

She loved books, and although she couldn’t read, would memorize her favorite stories and flip the pages as she recited the words.

Although strong-willed and outspoken, Milena somehow bypassed the infamous “terrible twos” stage, preferring to hand out tight hugs and sloppy kisses instead of temper tantrums.

Milena was it for the Avilas, and they were happy.

Blindsided

On May 15, 2011, the Avilas started their day at the Chino Hills swap meet followed by a Costco run at the District at Tustin Legacy to pick up some essentials.

They waited on Edinger Avenue to make a left-hand turn into their housing complex at Kensington Park Drive.

The arrow turned green, and as Jose pulled into the intersection, Catherine saw it: an Acura barreling down at more than 50 miles an hour.

The 68-year-old driver didn’t see the red light and didn’t hit her brakes.

Catherine heard the sickening crunch of metal slamming metal as the driver of the Acura broadsided the Avila’s Honda Accord.

The Accord was thrust into a spin.

Avila felt the airbags slam into her body and smelled the gun powder-like aroma it left lingering in the air.

When their car came to a stop, Catherine jumped from her vehicle but crumpled to the ground — the result of a broken hip doctors would later discover at UCI Medical Center.

She pulled herself up and limped to the back seat to check on Milena.

“I could tell right away something was wrong,” she said.

Catherine started CPR, then several Tustin police officers pulled her off her daughter.

Catherine Avila recounts the auto accident that killed her 3-year-old daughter, Milena.

Photo by Christine Cotter

Split-second decision

Officer Brad Saunders doesn’t remember anything about May 15, 2011 before the call at 4:20 p.m.

When the call about a violent traffic collision involving a couple and their child at Edinger Avenue and Kensington Park Drive went out on the radio, Saunders knew it was bad.

He arrived to find a hysterical blonde woman screaming as officers tried to keep her calm.

Saunders walked over to the Accord, set his eyes on the little girl, then looked up to scan Edinger Avenue for the sight or sound of a fire engine.

“If the fire department is rolling code 3 [lights and sirens]you should be able to hear them,” he said. “I could see up and down Edinger, all the way up to Jamboree and all the way down to the freeway and there was no fire engine in sight.”

He looked back at Milena in her car seat. The little girl in the light-colored dress wasn’t breathing.

“I could tell she was critically injured,” Saunders said.

Saunders pulled out his knife and cut the straps of the car seat and turned to his colleague, Officer Ronnie Sandoval.

“Let’s grab her and go,” Saunders told Sandoval.

Saunders cradled the little girl, careful to use his forearm and hand to support her spine.

He slid into the passenger seat of Sandoval’s patrol car, laying Milena across his lap to start CPR while Sandoval drove to Orange County Global Medical Center, then called Western Medical Center, in Santa Ana.

They pulled into the trauma center in minutes — three, by Saunders’ guess. When they arrived, Milena’s heart was beating.

About 20 seconds after they handed her off to trauma surgeons, the officers heard over the radio that medical aid had arrived to the collision scene.

“That was the hardest decision I’ve ever made in my career,” Saunders said. “I had a 3-year-old girl I was trying to keep alive.”

Tragedy and hope

Catherine and Jose Avila were taken to separate hospitals — she to UCI Medical Center and he to Global Medical Center, where he was released after an evaluation and where the officers took his daughter.

Catherine suffered a broken hip and some bumps and bruises from the impact, but she refused to stay in a separate hospital.

“I checked myself out and an officer drove me over to (Global) Medical Center,” she said. “I remember asking everyone to be straight with me and tell me what was going on, but nobody would.”

Catherine, pushed in a wheelchair and wearing a hospital gown, was taken to the floor Milena was being held where she was greeted by a sea of grieving faces.

Her family was lining the hallway of the hospital wing. Some cried harder when they saw her enter the corridor.

Catherine was pushed in the wheelchair through a set of double doors where she saw another sea of faces —unfamiliar, but all in uniform.

She recognized one man — the officer who had pulled her daughter from their car.

Catherine scanned the room until her eyes met her husband’s.

“Is she OK?” she asked.

Jose shook his head.

“No, she’s not OK.”

Catherine was pushed into the room where her daughter lay. She looked as if she were sleeping.

The doctor told her there was nothing they could do — Milena had suffered severe brain damage in the crash.

“Fix her,” Catherine demanded of the doctors. “Just make her wake up.”

The doctor insisted Milena was gone.

“It was really hard for me to wrap my brain around,” Catherine said.

Catherine Avila lost her three year-old daughter when her car was broadsided. She now makes gift boxes for police to give to other families who have lost a child.

Photo by Christine Cotter/Behind the Badge OC

The Avila family spent the evening of May 15 with Milena. Her grandmother gave her a bath, and family members took turns holding her hand and hugging her.

“We got to say goodbye, and we got to pray,” said Julie Chassagne, Catherine’s sister. “She was still a child that we could all hold, and we could all hug one last time.”

These were moments that wouldn’t have been possible if not for Saunders, Catherine said.

“She would have died at the scene and sat there for hours with a sheet over her until the Coroner’s Office came to pick her up,” she said.

The Avila family decided to donate Milena’s organs — her heart, lung, liver, kidneys and corneas.

Two children and a mother of three were among those who benefitted from Milena’s donation. Catherine also was told her daughter’s corneas would help restore the sight of two people.

These things also would not have been possible had Saunders not pulled Milena from the wreck that day.

“It was because of his choice Milena was able to save those other people,” Catherine said. “Kids have their mom now and other parents still have their children and they’ll go on because of that one split-second decision he made.”

Added Saunders: “That is the only thing I take comfort in. There were some positive things that came from her death.”

Milena was buried at Santa Ana Cemetery wearing a pair of pajamas handmade by her grandmother. Her family placed photos and books in her casket, along with a little cream-colored ceramic heart. Catherine wore a larger cream-colored heart around her neck.

The Tustin police employees touched by the tragedy went to the funeral, too. They placed roses wrapped with Tustin PD badge stickers on her tiny casket.

Saunders thinks of Milena before every shift he works and carries the funeral prayer card with him every day.

“There are those calls that you can’t get over and this is mine,” he said.

A headstone at Santa Ana Cemetery honors the Avila’s first two children — Jimmy and Milena. Jimmy died as an infant from complications with pneumonia and Milena was killed in a traffic collision at age 3. Catherine Avila now hopes to bring comfort to other grieving families with her project, Box of Hope. Photo courtesy the Avila family.

Finding faith

Comprehending the loss of one child is unimaginable, but the loss of both of your children seems impossible.

From overpowering anger to insufferable sadness, Catherine and Jose experienced it all, but there also was hope.

“I grabbed on strong to building my faith,” Catherine said. “I felt like this had to have happened for a reason even though I didn’t have the answer yet. I’m here to figure that out.”

Catherine, 36, returned to her job as a one-on-one aide for the Tustin Unified School District in a program for autistic students and Jose, 39, returned to his job as a UPS driver.

They celebrated Mother’s Day and Father’s Day the year Milena died, and also showed up to family gatherings and holidays.

“We didn’t skip Christmas because it would be hard. It still is hard,” Catherine said. “And it isn’t just Christmas that is hard, it could just be a Sunday afternoon (that is hard).”.

“We know we can get through thoseSunday afternoons because we have already gone through the worst Sunday afternoon.”

Saunders kept in touch with the couple as well — Milena’s death forever claiming a piece of his heart and his memory.

“I remember I needed to talk to you after this happened because it was important for you to know that I treated her like she was my own,” Saunders told Catherine as she held onto his hand on a recent Tuesday afternoon at the Tustin Police Department. “It was important for you to know that I did my best.”

Jose and Catherine Avila mourn the loss of their 3-year-old daughter, Milena, who was killed in a traffic collision. Catherine Avila now works with her sister to give comfort boxes to grieving families. Photo courtesy the Avila family.

Moving forward

A little more than a year after Milena’s death, Catherine was sitting in the cemetery at her children’s gravesite reading, as she often does.

She would see other grieving families say goodbye to their loved ones, but one service in June 2012 drew her in more so than the others.

A large crowd had gathered for the funeral of a 6-year-old who was killed in Santa Ana when a drunken driver hit her while she walked in a crosswalk with her sister and mother.

“I remember I wanted so badly to go over to the mom and tell her, ‘You’ll be OK,’ even though that’s not what I had wanted to hear,” she said. “I wished I could do something.”

That service stayed vivid in the back of Catherine’s mind as her life moved forward.

Part of moving forward from tragedy meant creating a family again, although the couple had said they wouldn’t have any more kids because of Catherine’s difficult pregnancies.

“Once we lost Milena, I knew I was going to do whatever I had to do, even if I had to be on my back for 40 weeks,” Catherine said. “I thought, ‘I know I’m here to be a mom. I feel it in my soul.’”

The Avilas welcomed their daughter, Faith, in 2013 and their daughter, Cruz, in 2014.

But the loss of her first two children continued to weigh heavy.

“We were under the assumption that we weren’t going to be able to have and keep our babies; that we were always going to lose them,” Catherine said. “It wasn’t that I was scared, I just thought that’s how life was going to be.

“Now, I’ve let that go and I just try to really enjoy them.”

Letting go of that fear also came with letting go of resentment, anger and negative feelings about the crash, and letting other, more positive, feelings in.

Helping others heal

Catherine transformed her grief into something to help others: Box of Hope, a program she runs with her sister, Julie, that donates boxes, such as the one given to the family who lost a triplet in February.

A gift box Catherine Avila created to give to families who have lost a child. Avila calls the comfort boxes, Box of Hope. She and her sister have partnered with Tustin PD to get the boxes to grieving families. Photo

Photo by Christine Cotter/Behind the Badge OC

Catherine knew what to put in the box — a collection of items that helped her through her darkest times.

She found comfort in the cream-colored ceramic heart she wore to remember her children (She also has a heart necklace for Jimmy) knowing they each wore the smaller heart around their necks, too.

And every year on Milena’s birthday and the anniversary of her death, the Avilas light a candle to honor their little girl.

At Jimmy’s funeral, which was two weeks before Christmas 2006, the Avilas handed out crocheted angel ornaments so Jimmy would be remembered during the holidays.

Catherine also remembers feeling lost when the funeral director for Jimmy’s service asked what she wanted in his casket, so she gives families a small blanket handmade by her mother and a stuffed animal to place in a child’s casket should the family feel at a loss when faced with such a question.

In the days following her children’s deaths, Catherine remembers having no appetite and feeling exhausted, but Chamomile tea seemed to calm her.

Everything in the box provided some kind of comfort as Catherine grieved, and she hopes it will do the same for others.

“You think (losing a child is) never going to happen to you and if it does, you feel like you are the only one on earth going through it,” she said. “If one person opens the box and realizes there is another mom out there who just might know what they are going through, it’s worth it.”

Catherine Avila wears two ceramic heart around her neck to remember her children, Jimmy and Milena. A smaller cream-colored ceramic heart was buried with each of her children. This necklace is one of the items she puts in Box of Hope to help grieving families who have lost children. Photo courtesy the Avila family.

Spreading hope

Catherine and her sister, Julie, have partnered with Tustin PD to launch Box of Hope (the tragedy also inspired Julie to serve as secretary with the Tustin Police Foundation). The sisters have delivered four boxes this year so far — one in Tustin to the family who lost one of their triplets and three donated to another agency.

“It’s my hope that one day this will be in every police agency because it’s a wonderful tribute,” Hardacre said.

Added Saunders: “There’s a very hopeless feeling when we go on a call and there is nothing we can do to fix it. This helps us cope, too, because this is something tangible we can offer a family who has just had a loss.

“And this is a great way to honor Milena.”

Honoring her daughter is all Catherine really wants.

“It was always my biggest fear that people would forget Milena,” she said. “You see that life goes on and life gets busy, but to have people remember her is more comforting than anything.”

Donations for Box of Hope can be sent to the Tustin Police Foundation, a nonprofit organization, by visiting tustinpolicefoundation.org or contact Box of Hope at boxofhope.tustin@gmail.com.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge