The suspect wrestled the officer to the ground then wrapped his legs around the officer’s waist.

The officer clasped his hands together and pressed his elbows hard into the suspect’s thighs, breaking the leg hold.

With a twist of a wrist, and a flip of the forearm, the officer flopped the suspect onto his stomach.

Then an was arrest made. A practice one, anyway.

Tustin PD’s held mandatory arrest and control training over several days for officers. Department instructors use Judo-inspired pain compliance techniques.

Photo by Christine Cotter/Behind the Badge OC.

Members of the Tustin Police Department this month participated in state-required training to review arrest and control techniques and learn new methods.

“This is part of our perishable skills training, which are the skills we use most often — driving, tactical communications, arrest and control and force options,” said Tustin PD Sgt. Sean Quinn. “We teach these skills so if an officer needs to use them, they do it properly and safely.”

Tustin PD uses a martial arts-based defense system that encourages officers to use their own body weight, and the bodyweight of the suspect, to gain control of a situation.

Getting into a knock-down, drag-out fight is rare for most officers, Quinn said. Of about 90 Tustin PD officers casually surveyed before the training, only three said they have ever been in a toe-to-toe fight with a suspect.

But use of force situations do happen — at least one every couple weeks in which officers need to use some degree of force — which is why it’s important officers are reviewing techniques and learning new skills.

“Our No. 1 goal is to keep our officers safe. I want everyone to go home to their families at the end of the shift,” Quinn said. “But we also want to keep the people we are arresting safe. We don’t want to injure anyone.”

Tustin PD Officer John Hedges, left, is one of several instructors for Tustin PD’s arrest and control course.

Photo by Christine Cotter/Behind the Badge OC.

However, injury is not the same as pain, Quinn pointed out.

Police use pain compliance techniques to cause temporary discomfort to subdue a fighting suspect.

Their main focus: to get control of a suspect’s hands.

When the officers practice, they fully execute each of the moves, which was obvious by the sporadic grunts coming from some officers when they role played as suspects.

“We want them to experience what it really feels like so they know how it should feel when it’s applied correctly and they understand the level of pain the suspect is feeling,” Quinn said. “If you’re applying force or pain compliance, you have to give people time to recover and you have to give them time to do what you’re telling them to.”

They worked on search and arrest techniques, the proper way to apply a wrist lock and what to do if a suspect wrestles an officer to the ground, among other skills.

Then they took turns sitting cross legged as their counterparts applied the carotid hold, tapping out before losing consciousness.

“Properly applied, it’s really safe,” Quinn said. “As soon as it’s released, it only takes about five to seven seconds to regain consciousness.”

But there is a way to avoid ever having to experience what a wrist lock or carotid hold feels like: Don’t fight in the first place.

“We want to gain voluntary compliance. We want people to do what we’re asking,” Quinn said. “That’s the ultimate goal in police work.”

Tustin PD’s Officer Javon Smith takes down a fellow officer to demonstrate correct arrest and control technique.

Photo by Christine Cotter/Behind the Badge OC

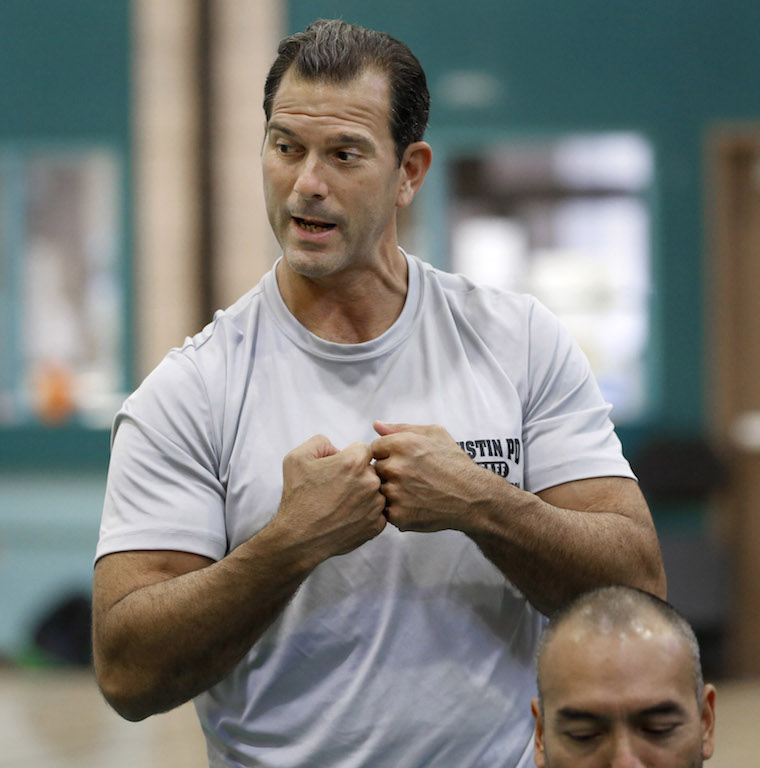

Tustin PD’s Sgt. Sean Quinn instructs fellow officers during an arrest and control training session.

Photo by Christine Cotter/Behind the Badge OC

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge