She started the same way she always does — perched on the edge of her couch in her living room, lap desk readied and a bright lamp illuminating a blank sheet of paper.

Radiohead played in the background — or maybe it was heavy metal that time — but either way, there was music to get her focused.

La Habra PD sketch artist Wendy Guandique drew for hours then sent a text of the composite with a message: “How’s this?”

The woman who received the text requested changes until the sketch staring back at her was the man she chased down apartment stairs after he grabbed her buttocks in a housing complex.

This sketch was one of two Guandique had drawn for the Fullerton Police Department as they investigated the “serial butt grabber” case. Although it was never released to the media, detectives used the drawings as they interviewed victims, Guandique said.

Almost every time, police said, the victims identified one drawing as the man who assaulted them.

When Fullerton police in February arrested Jose Alfredo Gradilla-Cuevas after an exhaustive five-month investigation, (he later pleaded guilty to 16 counts of misdemeanor sexual battery), Guandique immediately went to the Fullerton PD website to view the press release which displayed the booking photo.

“I knew right away when I saw it my sketch was pretty spot on,” she said. “This was a neat example of how vital witnesses can be for cases. Everything he (Gradilla-Cuevas) was doing was escalating, so it was good they caught him in time.”

La Habra PD employs two sketch artists to assist in investigations: Guandique, who works as the secretary to the chief, and Lt. Dean Capelletti, who serves as the investigations bureau commander.

Their skill provides an important tool in helping to identify suspects in a variety of crimes from sexual assaults to attempted kidnapping.

Their expertise is also something of a rare commodity in Orange County, with La Habra PD being one of just a handful of agencies with in-house sketch artists.

“It’s a medium that is not used a lot,” Capelletti said. “So we offer it to any police department in need, as a mutual-aid.”

Artistic discovery

La Habra PD discovered it had two artists in its employ by chance.

Capelletti’s artistic inclination was revealed after he poked fun at a colleague more than a decade ago.

“You know how it is with police, always making fun of each other,” he said to preface the story.

In the winter of 2003, the avian influenza, more commonly known as the bird flu, became a public health threat in Orange County. Health officials warned the community to steer clear of any dead birds and immediately report them.

So when one La Habra officer was called to handle a bird carcass in the road, a pithy cartoon was in order.

Capelletti, who once worked as a children’s clothes designer long before wearing a badge, drew a sketch of the officer delivering CPR to the bird and shared it with his fellow officers for a chuckle. Somehow, a copy of the drawing made its way to his superiors.

Not long after, Capelletti was sent to training and certified as the department’s first sketch artist.

As he promoted, Capelletti’s heavy work load rendered him unable to sketch very often.

He then learned his colleague and friend, Guandique, also had an art background.

Guandique joined the department in 2007 as a dispatcher, before serving in the records department, then as secretary to the chief.

She grew up loving art and law enforcement.

“As I kid, I was glued to watching ‘America’s Most Wanted’ and they did a feature on composite artists and forensic artists,” she said. “I was just fascinated by the work they did.”

Guandique would pull her mother’s encyclopedias off the shelves and thumb through the pages, sketching whatever images piqued her interest.

“I remember I used colored pencils to sketch a catalogue of birds and I would try to see how close I could get to the colors and shapes in the pictures,” she said. “That’s how I spent most of my time — drawing.

“It’s funny that this whole thing went full circle. I had no idea this is where I would end up — actually doing the very thing I wanted to do as a kid.”

Guandique took art classes in high school and broadened her skills in college. When she joined La Habra as a dispatcher, she was interested in becoming certified as a composite sketch artist, but didn’t ask to pursue training.

Capelletti encouraged her to inquire about getting certified and in 2011, the department sent her to the 120-hour POST (Police Officer Standards and Training) course.

Her training didn’t end there.

“Every two years we have to get re-certified because it’s considered a perishable skill,” Guandique said. “And every two years when we come back, they have new tools for us.”

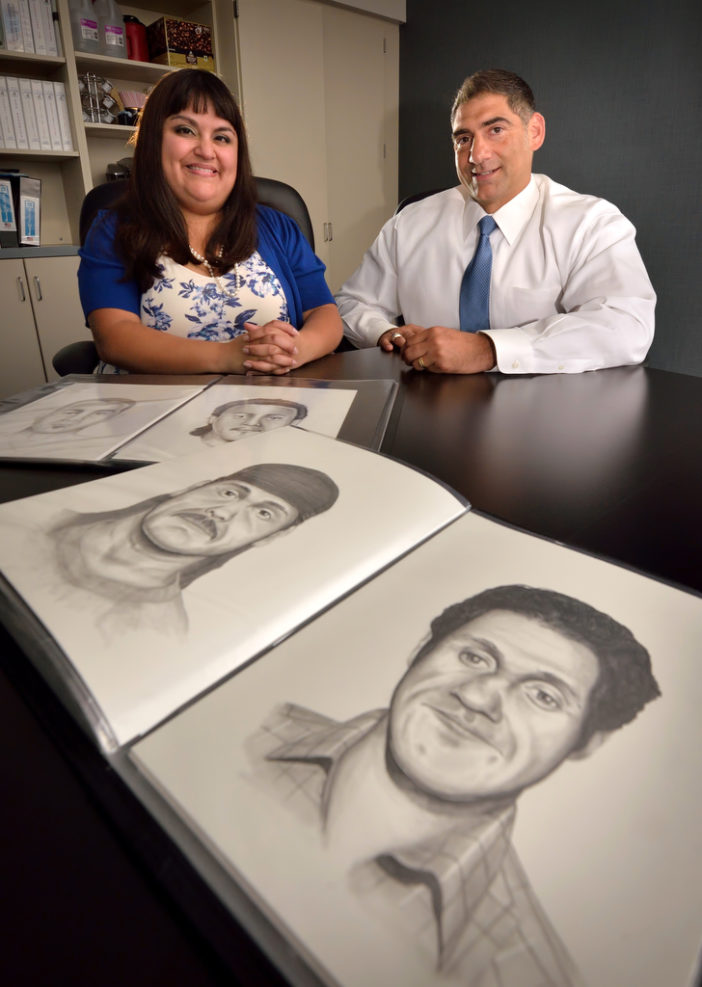

Wendy Guandique, left, and Lt. Dean Capelletti, sketch artists for the La Habra PD.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Training to sketch

Both Guandique and Capelletti said while an art background helps, it is not a requirement to become a composite sketch artist. (Capelletti’s impressively realistic drawings of George Clooney and Mark McGwire seem to prove otherwise, but we’ll take their word for it.)

The POST-certified course starts from the basics.

Guandique remembered someone in her class drew a stick figure on the first day because they said that’s all they knew how to do, but by the end of the course, their portraits rivaled others with art training.

“If you have the passion to do something and you have the discipline to learn, you can excel just as well as somebody who has the natural ability to do it,” she said.

The course teaches how to draw a variety of facial features, how to ‘age’ the subject of a photo for missing person cases and how to interview witnesses and victims — a critical part of getting an accurate sketch.

“The most important thing is not to influence them at all,” Guandique said. “You can’t feed them any characteristics because you can inadvertently implement something that really isn’t in their memory.”

They also use an FBI photo reference book for witnesses to flip through and point to whatever type of chin, hairline, nose or eye shape the suspect had to combine facial features into an accurate sketch.

“A person might not remember exactly every part of the face if you ask them to describe it,” Capelletti said. “That’s why you separate it into pieces then draw the composite of what they point out.”

It can take several hours to put together a sketch, even then the witness or victim usually asks for changes, until it best represents what they remember.

“Once they’re able to see the draft of the sketch, it can trigger something and they might remember more specific characteristics,” Guandique said.

Added Capelletti: “A common misconception about composite art is that if something happened today, I need to do a drawing right away,” he said. “That’s not true. It is driven by the victim or witness, we work with their schedule.”

“When you have a traumatic moment, it creates a type of ‘scar’ in your brain that will be there forever. The image, that moment is there; it’s just a matter of bringing it out.”

The art of investigation

The ‘serial butt grabber’ case is just the most recent investigation that La Habra’s sketch artists helped with, but over the years, they have been tapped to help on a variety of cases.

Capelletti’s sketch of a man who in 2009 stabbed two people in a Fullerton movie theater helped investigators track him down and arrest him in North Las Vegas. The suspect was convicted of attempted murder.

Guandique’s sketch of a man who exposed himself several times outside a La Habra school helped officers find and arrest that suspect.

Not every sketch is released to the community, however. The detectives keep some on-hand as investigation tools.

Guandique worked with Buena Park on two separate cases involving children being assaulted at two local parks — one in which a little girl was attacked in the bathroom, and another in which a man attempted to kidnap a young boy from a park bench.

Both children escaped their attackers.

Cases like these — the ones involving children — are always the most eye-opening for Guandique.

“I think the youngest I’ve had to interview was a 9-year-old boy,” Guandique said. “I’ve just been impressed with child witnesses because they are very vocal and the minute they are comfortable enough, they can paint a vivid picture of what happened.”

“But it really impacts you, because it reminds you of what’s out there.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge