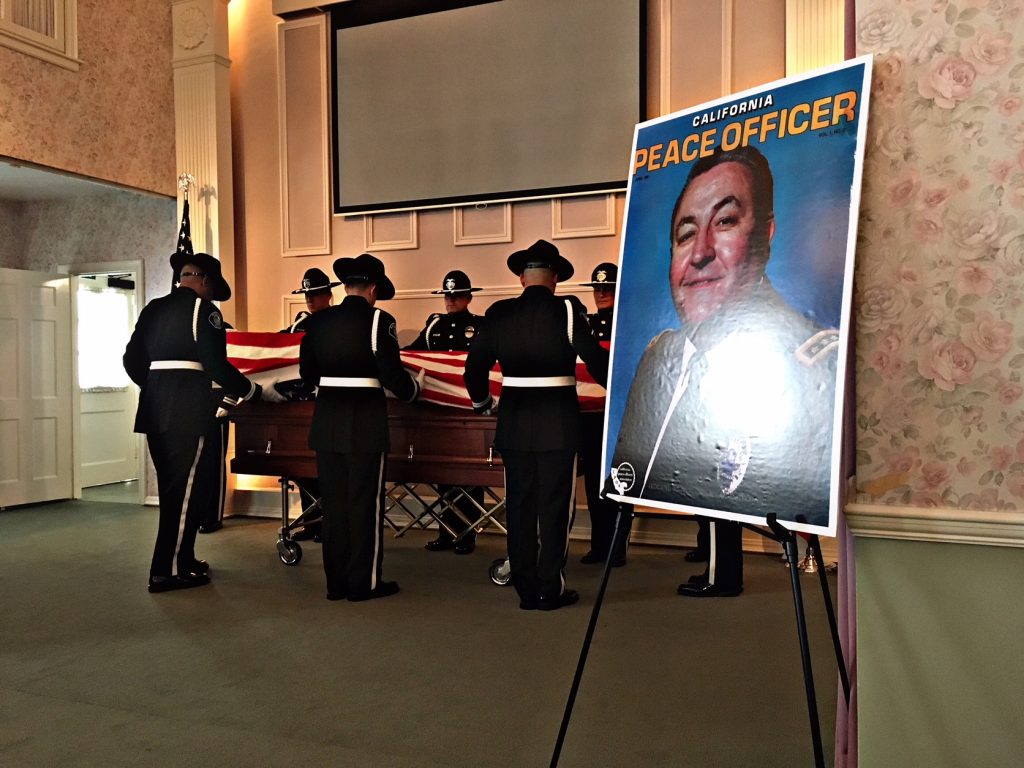

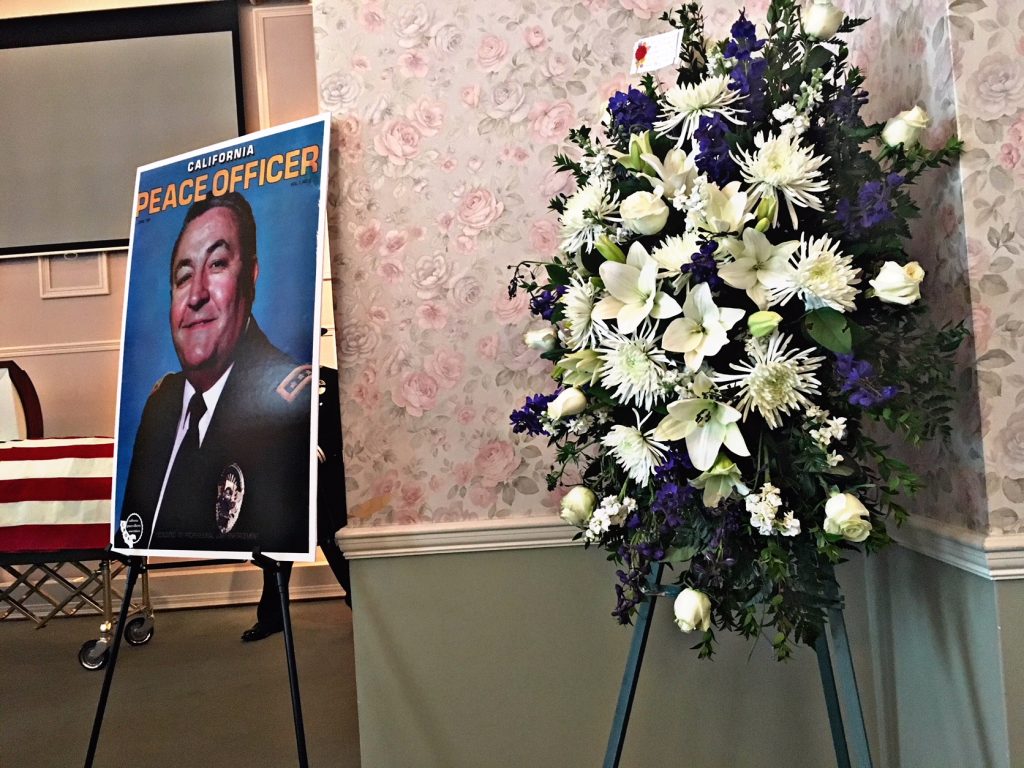

Editor’s Note: Former Santa Ana PD Chief Paul Walters, now chief of the bureau of investigations for the Orange County District Attorney’s office, presented the following eulogy at funeral services held today, April 4, for former SAPD Chief Ray Davis, who died Thursday, March 29.

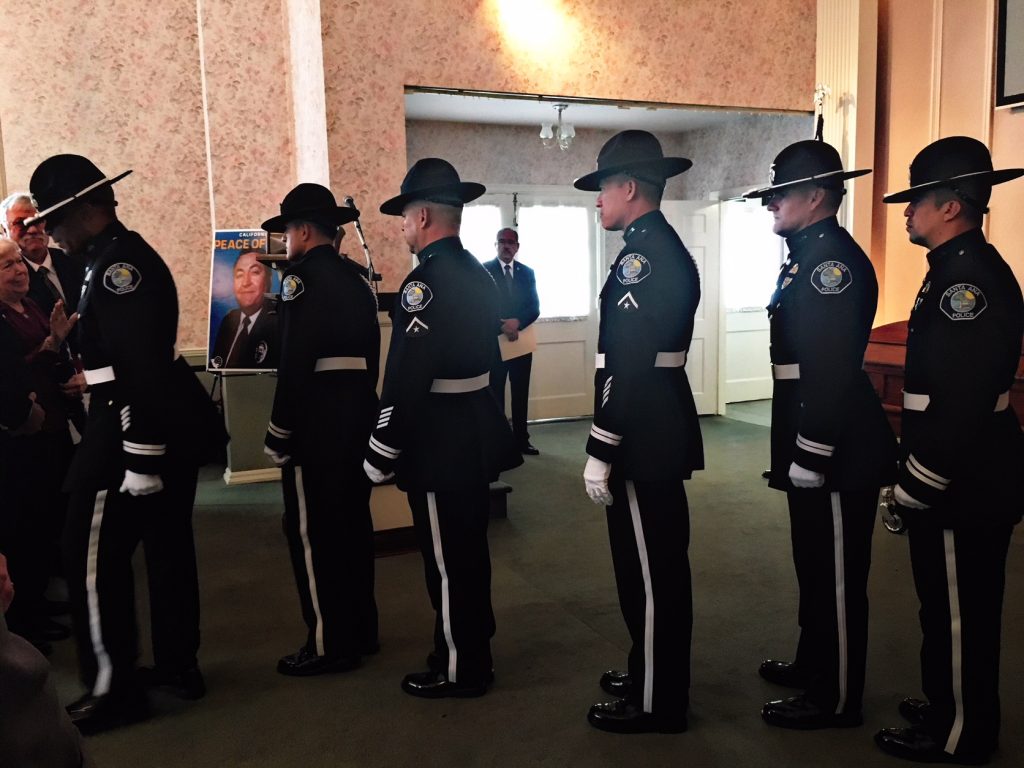

Davis’ funeral was held at Brown Colonial Mortuary in Santa Ana, with a flag folding and honor guard presentation immediately following. Gravesite services will be conducted in Fentress County, Tenn., at a later date. Walters was an officer under Davis and eventually succeeded him as Santa Ana Police chief from 1988 to 2013.

Thank you all so much for being here today to honor a true role model and an inspiration for me personally, Chief Ray Davis.

Now, I don’t think that, as a rookie cop, Chief Davis intended to be a legend, but he certainly became one.

Once, out of curiosity, I asked some of the old timers at Fullerton what kind of street cop he was and they said he was an excellent officer — a hard charger, and he worked non-stop every day to keep the community safe.

They told me a couple of stories — not sure how true they are, but they said he got on a train once and cited the engineer for blocking traffic in Fullerton because the train was stopped too long backing up traffic for miles. And another time he was working traffic on a motorcycle and he could not get the driver of a Corvette to stop for speeding so he threw a flare into the open window to get him to pull over.

That stuff is legendary.

I asked Chief Davis if those stories were true and he just laughed and said they exaggerate. I leave it to you that knew him to decide whether they are true or not. For me, I can picture him getting on the train and citing the engineer, but the flare through the window? Not so sure about that one.

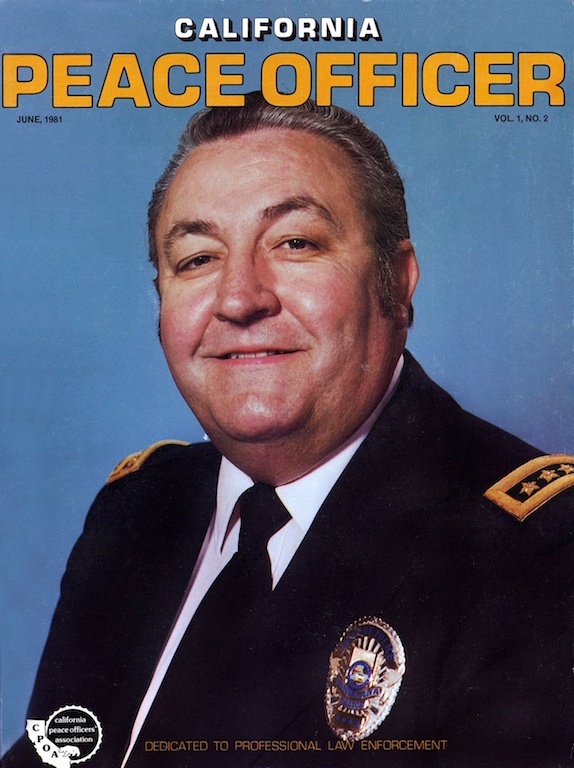

While those stories may fall just short of urban legend, there is no denying that Chief Davis was a powerful visionary and leader in policing — not just in Santa Ana, Orange County or the State of California but in the nation. And he was a major contributor to America’s law enforcement history of innovation, community policing and professionalism.

Chief Davis’ policing philosophy, historical strategies and achievements have been studied and written about by some of the foremost researchers and experts in policing that this country has even known.

Police leaders from around the country came to Santa Ana to study how we did business so they could transfer his strategies and innovative ideas back to their own departments. Chief Davis even followed up by sending his own staff members to their departments to help them with their transformation projects. He sent me to Boston PD and to Houston PD in Texas to help their departments.

I started my career in policing at the Santa Ana Police Department in 1971, just out of serving in the Air Force during the Vietnam War.

Edward J. Allen was our police chief then — the first appointed chief in the history of the department. Prior to Chief Allen, all of the police chiefs were elected to office until 1954.

Let me give you a little background on police life in Santa Ana before Chief Davis became our chief.

In those days, rookie police officers were put on the streets in full uniform, badge, gun and everything, before we went to the police academy.

I recall as they swore me in and gave me my badge they said show up for work tomorrow night. I asked what about the academy and they said, “Oh, we will get to that later.”

As a rookie officer, I started on graveyard shift. When I started my first shift, I was in shock. There were so few police officers on duty each night. We went from call to call just about every night. And to make things worse, you never knew what beat you were going to be assigned. As a result, you generally got to know the whole city but since you moved around so frequently you didn’t get to know any particular area of the city very well.

There were 10 beats, and the watch commander assigned you each night. Some beats were known for their serious crime problems. If we had enough officers a couple of those high-crime beats would be split into an A and B side. But because you had a beat assigned didn’t mean you would actually stay in it — you went wherever the dispatcher sent you, which could be anywhere in the city on any given night. There was no beat integrity. Your assignment just meant when you were free that is where you were supposed to concentrate your patrol time.

The game plan from the watch commander was simple: Don’t get involved in anything minor if you can help it, you need to stay 10-8 (that’s in service and available for all of you civilians) so you would be able to respond to the really serious crimes and arrest the perpetrators. The strategy seemed simple.

We had frequent acronyms we used a lot (maybe too much so) to decide on the disposition of our calls for service, such as GOA (gone on arrival) and UTL (unable to locate). They were part of our normal vernacular and they made for very short police reports.

We had an officer (Nelson Sasscer) killed in 1969 so we realized how important it was to have a backup and not do risky things alone when you needed help. Make sure you wait for your follow up, officer safety was heavily emphasized.

We had one-man cars unless you were a trainee, then you rode with a field training officerc(FTO) until you completed the academy and the field training program with an FTO.

After only a couple of weeks on the job, I got to experience first-hand how dangerous the job could be when, one night, two gangsters tried to kill my partner and me.

But the talk around the department was not just about how dangerous it was, how bad the equipment was, or how the patrol cars were worn out and the staffing levels were low. The discussion turned to who was leaving for a better police department and where was the best place to go serve out the rest of your police career.

A police agency is a paramilitary organization. You take orders and do the best you can with what you have or you decide to do something else or find another department. Many left for greener pastures and a safer environment and a slower pace.

I was actually one of those who considered doing something else and I met some former Santa Ana officers who had become attorneys by going to law school at night. So I enrolled in law school in 1973 with plans to leave the PD and hopefully become a deputy district attorney.

But later that year, the department and my world would be changed forever when Chief Ed Allen retired and the new chief from Northern California was announced.

It was Chief Ray Davis from the Walnut Creek Police Department, who had started his career in Fullerton and worked his way up the ranks. We were excited that we had a new chief and we sincerely hoped things would get better.

We were in for a real change. Not only would the department change quickly, it was unbelievable that one person could have so much impact on the department and the city in such a short period of time.

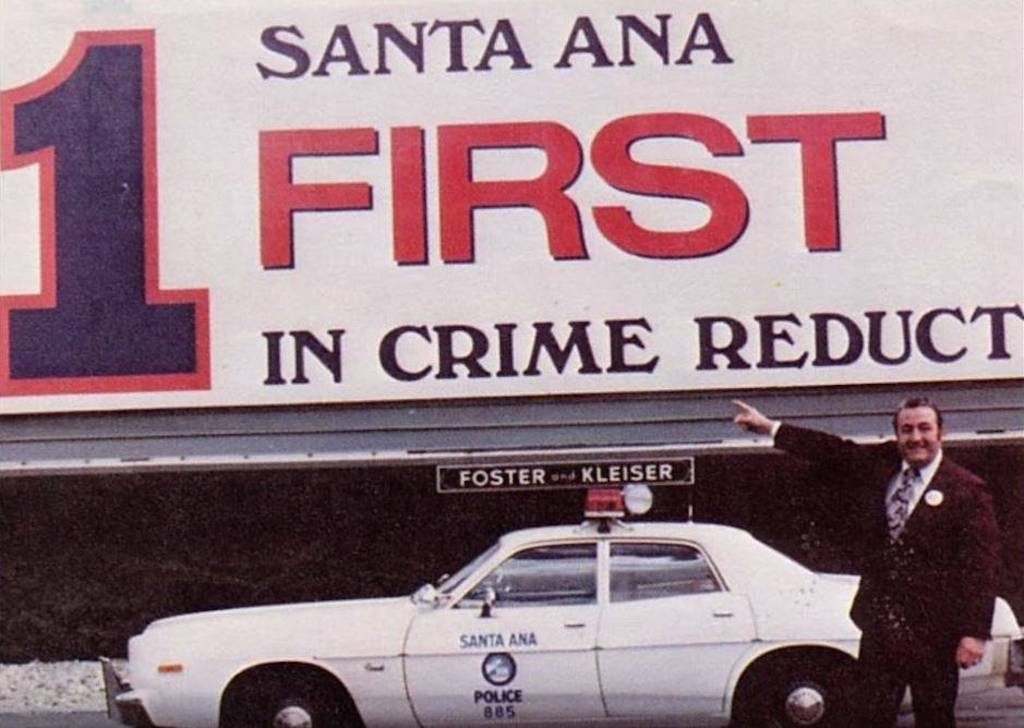

In 1974, we had the distinction of having the highest percentage increase in major crime in the state. Santa Ana also had the highest concentration of gangs and social problems, which greatly affected the crime rate.

While cities the size of Santa Ana held a staffing level of 1.86 per thousand population, Santa Ana had been in the level of close to half that for over 10 years.

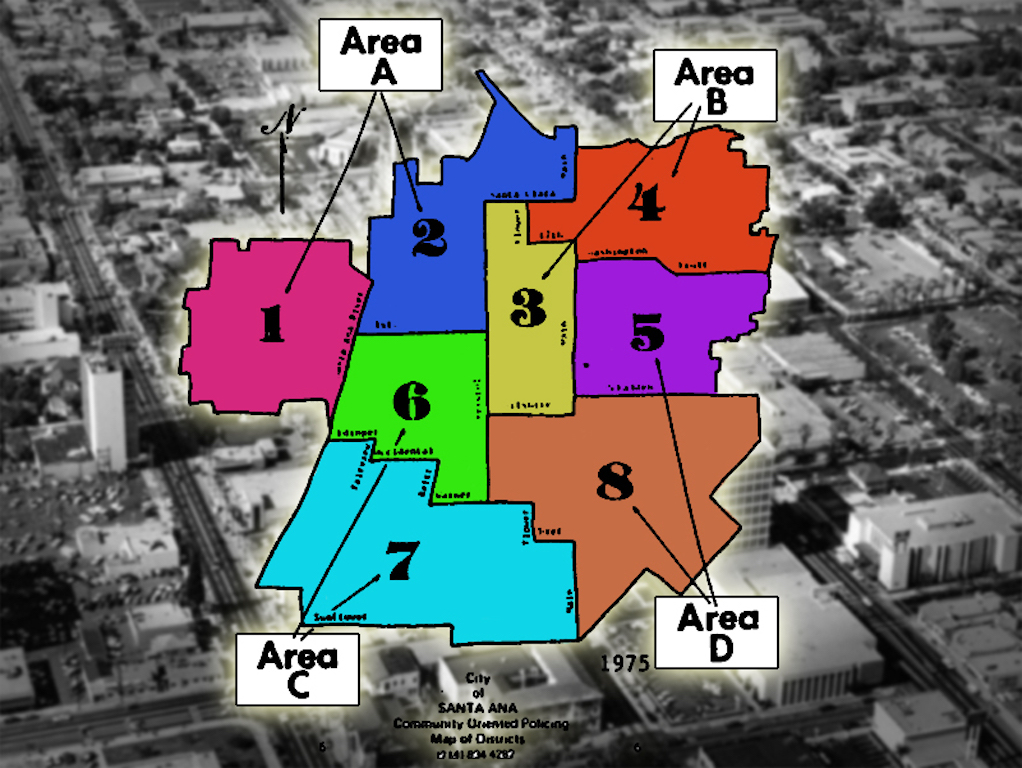

Chief Davis wanted us to test team policing before we added any officers to the department. It was readily apparent that we needed more staff when we tried the new deployment plan. The idea was for us to stay within our area or beats and not go into other areas unless it was an emergency. It was not long before the data showed it was not possible to maintain district integrity due to low staffing levels.

We talked about how futile the study was because we knew we did not have enough officers. But, we understood it was the chief’s way of developing the data to justify more officers for us and we were willing to do whatever it took to turn around the staffing levels of department. It was an interesting trial run, but we knew the purpose of the test.

Next, Chief Davis got the city council to raise taxes to add more officers to the department and we went into overdrive to try to get them recruited and hired. Not new recruits — the plan was to bring in experienced lateral bilingual officers from other departments that could hit the streets without the delayed time of going to an academy and through the field training program.

Chief Davis also wanted to hire civilians to do many of the jobs that didn’t require a police officer. He called them Police Service Officers, PSOs, and Community Service Officers, CSOs. They wore the police uniform but they were unarmed and not sworn police officers and the majority were women. And as you can imagine, this was not an uncontroversial decision.

Lt. Felix Osuna and Sgt.Raul Luna were some of the many outstanding lateral transfers over the years who helped Chief Davis to transform the department. I am sure they have some very interesting stories to tell you today.

You are also going to have the opportunity to hear from one of the very best today who rose from the civilian CSO ranks to one of the highest ranks in the department, retired Capt. George Saadeh.

It wasn’t long after Chief Davis took over before we realized that he was the real deal. He was a true leader who was going to turn around the department and we signed on for the ride. And it was a wild one!

From left, Louie Martinez, Felix Osuna, Tony Zavala, Paul Walters, Bob Helton and Raul Luna. Photo taken at April 4, 2018 memorial service for Ray Davis. Osuna was a lieutenant at SAPD along with Helton. Martinez currently is an investigator with the OCDA. He retired from SAPD as an investigator, as did Zavala and Luna.

He would routinely be out in the field at all hours and would call in on the police radio from his car requesting assistance from the officers.

Cops loved to play jokes on each other, but his voice on the radio was very distinctive. There was no way it was someone pretending to be the chief. The officers were jokers, but they weren’t crazy!

We had never heard the police chief on the radio and when they heard his police call sign, 31000, everyone paid attention and responded to assist him, no matter what they were doing. He was out on the streets addressing the issues firsthand. That spoke mountains to us. He knew what we were dealing with and going through, and we appreciated it.

He divided the city into four districts and had a lieutenant in charge of each area. The strategy was that watch commanders were the day-to-day supervisors who worked various shifts and the area commanders worked on long-term strategies with the community to address crime.

He also wanted the officers to work in districts for years before going on to other assignments. There was a field supervisor who served as the team leader and then the officers assigned to teams and the district with the expectation not only were you to respond to calls for service, but your job was also to get to know the community and work on partnership strategies to prevent crime.

Chief Davis was also a huge proponent of higher education. He negotiated agreements with the police union to pay officers and sergeants more if they completed their college degree. This was a huge help to the department in recruiting because of the recognition of education and at one point we were having around 75 percent of our lateral officers with a BA degree.

He believed, and the research has supported it, that educated officers are better employees and could deal with the role of being a police officer. Because Chief Davis was redefining the role of a police officer, he required a whole new set of skills to be successful in a Community Policing Department, and these skills were not taught in the police academy at the time.

He also changed the requirements to be promoted to lieutenant: You had to have a four-year college degree. You can imagine how this went over with the supervisors who had not completed their education but this was his key to changing the leadership to one that was progressive and it was not an easy task.

But Chief Davis had the ability to get things done when he believed it was best for the department and the community, and it worked.

It all worked so well that law enforcement executives from around the country paid attention to what Chief Davis was doing and how he did it. He completely transformed how a modern policing agency was supervised and led.

Chief Davis was having so much success with Community Policing, civilianization, minority recruitment and the ever-dropping crime rate, that he was recognized around the country. If this could be accomplished in a city as diverse as Santa Ana, with its numerous social problems, it could be employed with success anywhere in the country.

The department became so well known on the national stage for policing innovations that the TV show “60 Minutes” came to visit for several weeks in 1981 to study the department and do a story on community policing in Santa Ana. I was a lieutenant and area commander at the time and the chief had me show them around town and introduce them to community leaders for two weeks until they had completed their story of Santa Ana’s “COP Program.”

Chief Davis was very proud of the department’s success story when it aired.

Visitors who came to the department sometimes had their doubters, but once they met with Chief Davis, they soon realized there was really something to this thing called community policing.

I was extremely fortunate to have him as my chief. He promoted me through the ranks — sergeant, lieutenant and captain — and was a great mentor to me when I became chief of police in 1988.

After he retired, Chief Davis would call me from time to time. When I failed at something, he would boost me up and encourage me to keep things in perspective.

That is one of the things I admired about him the most: he was a strategic thinker, he could size people up and situations quickly and would know exactly what strategy would work, and I think it helped him to be so successful.

I know he helped me tremendously.

I told him repeatedly that he had done the heavy lifting at the department, and I had only built on the solid foundation that he had created.

I learned so much about leadership and being prepared for the tough battles from Chief Davis that I cannot describe them adequately in words.

Who knows where my life would have taken me and what the future of the city and department would have been without him. What a tremendous impact he had on all of our lives, and we are completely and infinitely indebted to him.

Recently I talked to Retired Chief Sal Rosano who served with him in Northern California. Chief Rosano and I had served on the Board of Directors of the California Police Chiefs Association, and he often asked about Chief Davis and how he was doing. He was a strong admirer of his accomplishments and his leadership skills.

He rightly summed up Chief Davis in very few words:

“He was a giant among men in many ways.”

Thank you.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge