In a recent National Institute of Justice Journal publication, a case was made for investing more in cold case investigations and use of DNA technology. According to the authors, an estimated 250,000 homicides remain unresolved, with more than 100,000 accumulated in just the past 20 years.

One of the reasons for the backlog may be the number of serial killers — killers who haven’t been identified and connected to crimes — that are active at any one time in the United States. How many are there? Estimates are as high as 2,000.

The National Institute of Justice assists departments across the country through the Solving Cold Cases with DNA program. More than 2,000 cases have had some resolution due to the resources the program provides.

Additionally, many unidentified homicide victims were likely murdered by serial killers. In addition, a significant number of people go missing every year. No one knows where they are or what has happened to them.

Some well-known serial killer cases have been re-examined for closure and victim identification.

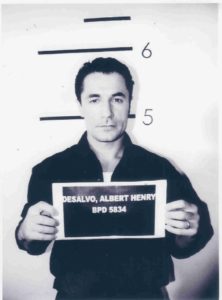

Albert Desalvo, AKA the Boston Strangler, recanted his confession of the murder of Mary Sullivan. In 2013, DNA evidence firmly established him as her killer. Mug shot from the Boston Police Department.

Albert DeSalvo, the Boston Strangler, recanted his confession of the murder of Mary Sullivan after his arrest. In 2013, his DNA was confirmed to match that found on the Sullivan’s body. The controversy of his culpability disappeared overnight.

In the notorious “Killer Clown” case, 30 bodies were discovered in the home of John Wayne Gacy. Six of the victims remained unidentified. Using DNA, two victims were identified: William Bundy in 2011 and Jimmy Haakenson in 2017. As familial DNA becomes more widely available, the hopes are to identify more victims.

Jimmy Haakenson’s remains were located in serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s subfloor in 1976. Haakenson was identified in 2017 thanks to a DNA match with family members. Photo from Cook County Sheriff’s Office

In the 1980s, the notorious Green River Killer operated in Washington state killing numerous women. Gary Ridgway was arrested in 2003 and convicted of killing 49 women. Many of the victims remain unidentified. Thanks to cold case investigators, Sandra Major was identified through a DNA match from a cousin in 2012.

Two of the most significant DNA serial killer cases are from California.

The “Grim Sleeper” was connected to homicides in the 1980s through the 2000s. After his son was arrested, familial DNA led investigators to Lonnie Franklin Jr., who was convicted of killing 10 women. He is suspected in as many as 40 more murders.

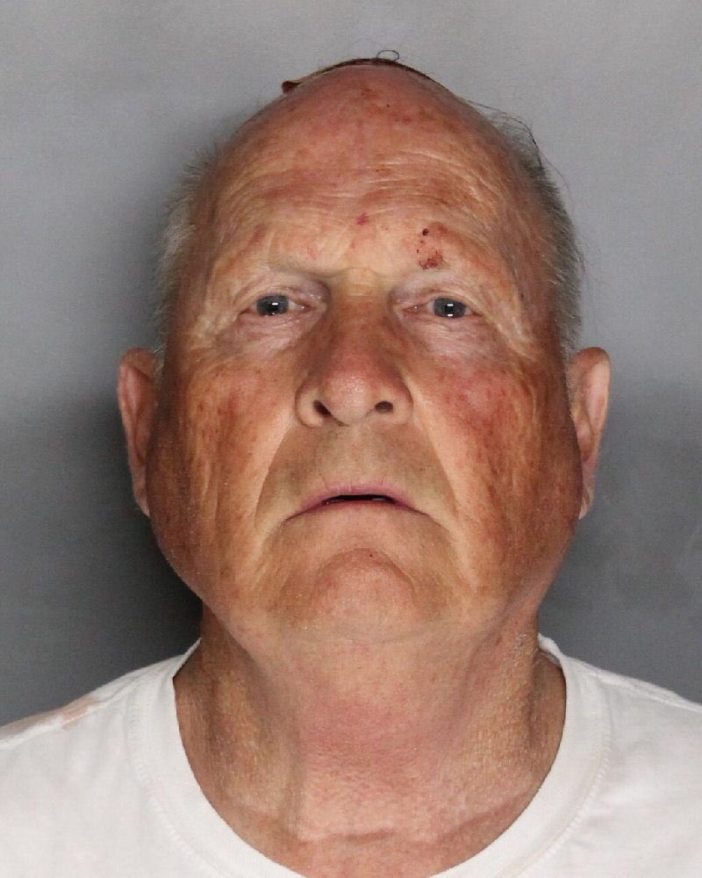

In 2018, Joseph James DeAngelo was identified as the suspect in the “Golden State Killer” cases from the 1970s through the 1980s. He was suspected of more than 50 sexual assaults and 13 murders. Using open source DNA records and forensic genealogy, investigators were able to focus in on DeAngelo.

And it’s not just high profile cases that benefit from using DNA evidence. Every day across the country agencies are solving murders with the use of DNA. In November 2020, the Westminster Police Department made an arrest in the stabbing death of a 22-year-old woman. Investigators arrested a suspect after several attempts at tracking down a suspect using familial DNA.

If serial killers can be caught early enough through open-source DNA, lives can be saved. Most serial killers keep killing until caught.

Investigations like this take time, effort and funding. But they also need to have access to open-source DNA databases to locate family trees of suspects.

This makes civil liberties advocates very nervous. The might argue DNA should be something that is private and not available to just anyone.

On the other hand, I can’t help but feel for the families of homicide victims who, decades later, have their questions answered. I’ve seen the relief and the tears that come in knowing. I’ve seen the hard and sometimes fanatical effort investigators pour into getting not only justice but closure for the families. And there is a real chance further killings can be prevented.

With technology, time, and funding, police agencies can make significant leaps forward in closing cold cases and identifying previously unknown victims. During a time of budget cuts and calls to defund the police cold cases can become less of a priority. That would be a disservice to our communities and the families of the victims.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge