The trail of blood stretched for two-and-a-half blocks in the Stanton neighborhood.

Two guys had gotten into a vicious fight involving knives and a baseball bat, and the blood was from one who ended up dying after he stumbled back to his house.

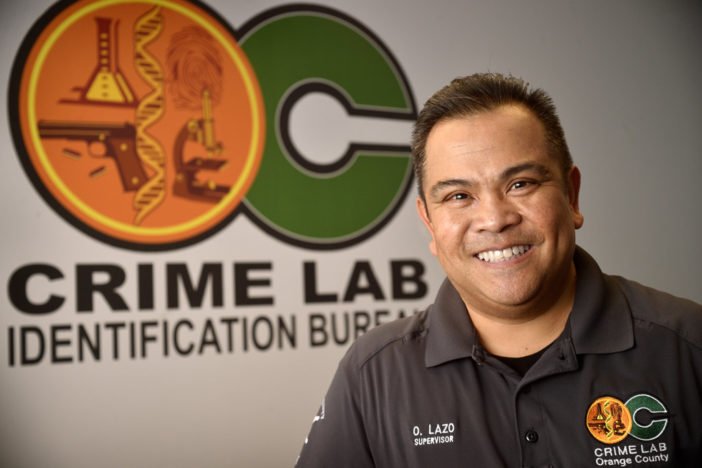

On this night in 2008, it was up to Omar Lazo and his partner, Andrew Hayes, to document and collect evidence for Orange County Sheriff’s Department investigators.

Hayes was a newly promoted lead forensic specialist with the OCSD’s Crime Lab Identification Bureau. Lazo was a forensic specialist.

Lazo and Hayes are among the OCSD’s 14 Crime scene investigation (CSI) professionals who respond to between 3,500 and 4,000 calls a year.

Callouts range from vehicle burglaries and home break-ins to major tragedies like the massacre at the Salon Meritage. The mass shooting at the hair salon in Seal Beach, on Oct. 12, 2011, claimed eight lives (Hayes was the main lead forensic specialist on that grisly scene).

The nature of a CSI specialist’s job is unpredictability.

“It’s difficult to train for everything,” says Lazo, a 19-year Crime Lab veteran who now supervises the CSI team. “But at least we try to prepare for everything.”

And that includes anticipating the whims of Mother Nature, from rains to winds to punishing heat — as well as terrain.

Lazo recently discussed the challenges of CSI specialists when they have to deal with the elements.

They come to a scene armed with an arsenal of investigative tools that allow them to do their job in even the most challenging of environments. For example, using chemicals, Lazo and his colleagues can pull latent (invisible) prints off a wet car. The chemicals also work on wet windows and rusty gates.

As they investigated the blood trail in Stanton, Hayes took photos of the scene as Lazo collected the evidence, which also included a knife and the baseball bat.

Suddenly, the skies opened up.

OCSD Supervising Forensic Specialist Omar Lazo gives a tour of the equipment kept inside Crime Scene Investigation vans.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

“The first thing, and really the only thing, that comes to our mind when something like this (rain) happens is preservation,” Lazo explains. “The documentation and the photographs all go to the wayside if it means we’re going to lose the evidence.”

As the rain came down, Hayes ran ahead of Lazo, photographing the blood trail, while Lazo collected the evidence. If Hayes had been alone, he would have skipped taking photos and instead make mental notes where the evidence was for later documentation.

“We had to change modes to evidence recovery rather than evidence identification,” Lazo explains.

Why not cover the blood trail with tarps?

“No, that would trap moisture underneath (and dilute the blood),” Lazo explains. “It’s better to pick up the evidence and go. The rain was significant enough that if we had left the evidence out, it would have been compromised.”

The rain diluted the blood that night, but the blood was concentrated enough to be used as evidence.

Blood acts in a very predictable way, Lazo says.

“When it falls, it has a pattern to it,” he says. “And that pattern tells a lot.”

If there’s an ellipse-shaped drop with a tail on it, the tail indicates in which direction direction the blood was moving.

A circular blood drop indicates blood fell directly perpendicular to where it landed.

Extreme heat poses other challenges.

In Arizona, if a body is found in a car, CSI investigators almost always bring the body along with the car into an air-conditioned garage to examine both together because it’s so hot outside, Lazo notes.

In Orange County, where the weather is relatively milder, CSI investigators leave everything in place and perform the investigation at the scene, he says.

Sometimes, during heat waves, that can cause issues.

Supervising Forensic Specialist Omar Lazo talks about his 19-year career at the OCSD Crime Lab.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Lazo recalls the July 4, 2003 stabbing death of a 13-year-old boy in Mission Viejo, the son of a chef whose girlfriend killed the young teen and also tried to kill him because he wouldn’t commit to a romantic relationship with her.

The killer, Tamara Kay Bohler, left a 3-mile trail of blood from her boyfriend’s house after getting into a struggle with him and stabbing him in the neck with a 10-inch kitchen knife.

Lazo and two other OCSD CSI specialists spent six hours collecting evidence along the blood trail, which mostly was on concrete. Bohler had wandered for 30 hours before police found her.

After a few hours with no water and no breaks, one of Lazo’s partners was showing signs of heat exhaustion.

“I noticed that she was not answering my questions and just kind of looked like she was staring into space,” Lazo says. “We sometimes get so focused on what we’re doing that we forget to take care of ourselves.”

No longer.

All OCSD CSI vehicles now are stocked with water, snacks, and canopies.

Lazo’s partner took a break and drank a lot of water, and was fine.

Lazo almost suffered heat exhaustion working a homicide in Fullerton in 2012.

Two transients got in a fight, and one died after being bludgeoned with a 2-by-4.

“It was 112 degrees at Fullerton Airport that day,” says Lazo, who was collecting evidence off the steaming asphalt.

“I wanted to get the job done,” he recalls. “I’m the guy that’s just a little bit tenacious when it comes to that stuff.”

After five hours, Lazo started walking in circles.

His partner rushed him to a convenience store, where he guzzled Gatorade.

OCSD Supervising Forensic Specialist Omar Lazo demonstrates how two chemicals can pull fingerprints off a wet surface of a car.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

When Lazo got home, he took all his electronics out of his pocket and jumped into the pool, fully dressed.

“In retrospect,” Lazo says, “I was just being stupid working so hard in that heat.”

STARTED AS A PHOTOGRAPHER

Lazo went to school for mechanical engineering but his passion for photography landed him a job in the OCSD’s Crime Lab.

“I started here in the photo lab,” he says.

Even he can’t believe he’s been doing CSI work for nearly two decades.

Lazo wouldn’t trade his job for a second. He loves it.

Some CSI TV shows drive him nuts.

“There’s a big misconception about cartridge casings,” he explains. “On TV, a CSI investigator will say, ‘Based on the location of the shell casings, the shooter was standing here.’ That doesn’t work at all. Where the shell casings end up have no direct relation to where the shooter was exactly standing.”

One “CSI” show showed an investigator using a flash to take a picture of an object at the bottom of a pool.

“That wouldn’t work,” says Lazo, explaining the flash would completely obscure any view below the surface of the water.

“But I get it. If TV shows depicted what we really did, they would be boring.”

Lazo notes that TV shows and movies always use plastic bags in the courtroom to hold up and display evidence – for example, a bloody knife – for dramatic effect.

“Plastic bags gather moisture and that would compromise evidence,” he says. “We always use paper bags.”

On another case, in which a woman’s decapitated body was flung into the wilderness off Ortega Highway, Lazo’s crew had to get geared up by a fire department search and rescue crew to rappel down the hillside to examine the scene.

Lazo wasn’t on the call, but it would have been right up his alley. Lazo is an avid rock climber, a rescue-certified scuba diver, and he has a black belt in Tong Soo Do.

Before every callout, the hard-charging CSI expert keeps one thing in mind – regardless of the weather:

“No one’s getting away with this,” Lazo says.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge