On a sunny morning in the Irvine Spectrum area, it’s hard to believe anything bad happened here.

Before being taken over by master-planned communities and upscale malls, or even its eponymous orange groves, Orange County was an untamed lawless land. Before it was bespeckled by Irvine Corporation projects, it was the definition of the Wild West. Infamous gangsters roamed or were pursued by similarly unchecked vigilantes through the canyons and arroyos of Los Angeles and later Orange County.

At a hillock, across the I-405 freeway from the Irvine Spectrum, one of the early, deadly ambush battles between lawmen and robbers was commemorated on Monday, April 1.

Former and current law enforcement officers from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Orange County Sheriff’s Department, and Irvine Police Department gather around a plaque commemorating the four law enforcement officers, including Sheriff James Barton, who lost their lives during a 1857 gun battle with outlaws at what is now called Barton Mound in Irvine.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

It was here, or hereabouts, in January 1857 in a gunfight with the notorious Flores Daniel Gang, that James Barton became the first Los Angeles County Sheriff killed in the line of service, along with a deputy and two constables.

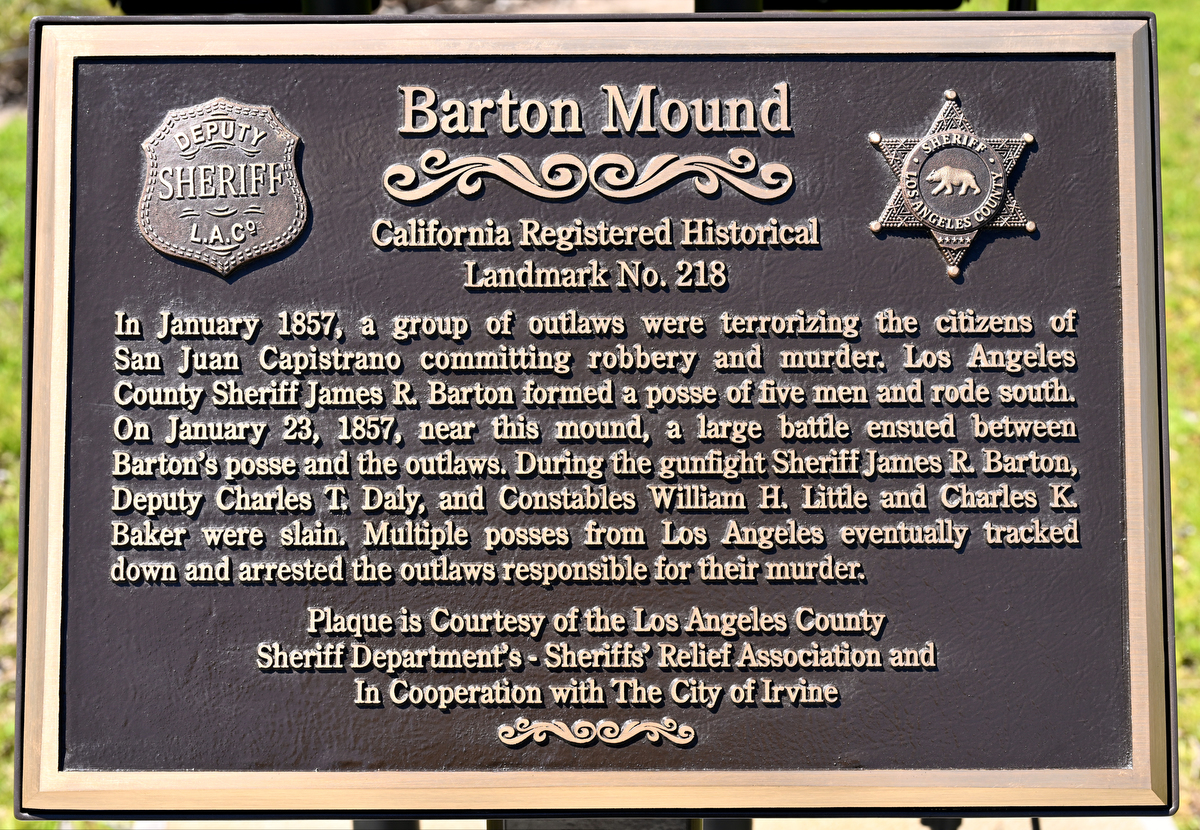

A mounted bronze on brown plaque on City of Irvine land reads “Barton’s Mound” and signifies the location as a California Registered Historical Landmark. The plaque is off the San Diego Creek bike path just west of the Irvine Company’s Los Olivos apartment community.

Although the battle between the outgunned posse and the robbers was well-publicized at the time and the State registered the location in 1933 as a State Landmark, the battle and Barton’s significance waned over the years without even a marker to indicate where it occurred.

Los Angeles Sheriff Robert Luna, who attended the unveiling of the plaque, was happy to witness the long overdue recognition which he said is a testament to law officers who have “a commitment to doing the right thing and putting the right people behind bars. This means we never forget.”

John Stanley, a retired lieutenant with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, gives an historical overview of the shooting at what is now called Barton Mound.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Earning recognition

Jerry Boyd is a former lieutenant and captain with the Irvine Police Department, now retired and living in Oregon. In 2021, he learned about Barton’s Mound, which was in an area where jogged regularly while with Irvine PD.

After learning of its significance, Boyd suggested on social media that someone should take up the cause of recognizing the site with a plaque. Retired LAPD Patrol Chief Tom Laing saw the post and thought it would be a simple process. At the time, however, he says the pandemic was shutting down a number of agencies.

Eventually, he met Irvine Councilmen Mike Carroll and Anthony Kuo. Carroll, a history buff who moved to Orange County from New York, said he remembered reading about the events at Barton’s Mound 20 years ago and was happy to assist.

John Stanley, retired lieutenant with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, gives an historical overview of the shooting at what is now called Barton Mound.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

He was struck that while there are at least a couple of Orange County historical landmarks that reference Juan Flores and his gang and plenty of legends about the bandit, few other than local historians had heard of Barton. Plaques at Flores Peak between Harding and Modjeska canyons, and Robber’s Cave in Aliso Woods, both regale visitors of Flores’ exploits, but until now there was nothing recognizing or commemorating Barton.

If not for Barton, Flores and Daniel may have gone down in history as little more than footnotes among the myriad murderous thugs of the time.

Kuo eventually authorized Irvine City Staff to research the Barton site, recommend installing a plaque, and work through the proper deeds and public works approvals.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna speaks during the dedication of a plaque commemorating the four law enforcement officers, including Sheriff James Barton, who lost their lives during a gun battle with outlaws in 1857 in Irvine, in what was then Los Angeles County.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Laing enlisted the help of other history buffs, members of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, the California Office of Historic Preservation, and the Sheriff’s Relief Association, which paid for the plaque and mounting.

Retired Sheriff’s Lt. Brett Parker, who scrambled to the top of the mound when the area was being inspected, said he was skeptical about getting roped into a project. However, when he heard the tale of Barton and the gunfight he said, “I’ll do THAT project.”

The mound overlooking the plaque may not be the exact place where Barton met his end. Other similar hills in the area were flattened and cleared for the building of the nearby freeways. However, the mound conforms with the existing historical accounts and descriptions.

“It may not have been this exact hill,” said historian and retired Los Angeles Sheriff’s Lt. John Stanley. “But it was in this general area.”

Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna speaks in front of the Barton Mound memorial plaque in Irvine commemorating the four law enforcement officers who lost their lives during a gun battle with outlaws in 1857.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

And now there is an exact place where people can learn a little history.

“I hope people will look this up,” Kuo said of the site. “I hope they’ll go for a walk and explore and take a moment to remember law enforcement.”

Deadly encounter

A quarter century before the gunfight at the OK Corral, before Quantrill’s Raiders sacked Lawrence, Kansas, or the James-Younger Gang became infamous — in fact and fable in Missouri — the Flores Daniel gang and other robber gangs created their own bloody legacy in Southern California and modern-day Orange County.

As often happens, the desperados garnered the headlines and grabbed the imagination.

While the rise and collapse of the California Gold Rush created its own fabled list of outlaws, from the Joaquin Murrieta and the Five Joaquins with Three-Fingered Jack, to “Rattlesnake Dick” Barter and “Charles “Black Bart” Boles, in what was to become Orange County the Flores-Daniel Gang was the most notorious during a brief, bloody run in 1856-1857.

Barton Mound in Irvine, where four law enforcement officers, including Sheriff James Barton, lost their lives during a 1857 gun battle with outlaws.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

At the time, Southern California was a caldron of discontent, with its mix of disenchanted miners, who had drifted south from Gold Rush country, angry, dispossessed Revolutionaries from the Mexican-American War, settlers from the East seeking to take over the land, and mistreated and displaced indigenous people.

“The convergence of groups led to an explosion of lawlessness,” said Stanley, who has written extensively on California lawmen killed in the line of duty.

According to Stanley, records show up to 44 homicides occurred in Los Angeles City in the first year-and-a-half of its existence, among a population of less than 2,000. The rate of killings between 1850 and 1861 was about 1.24 percent, or about 200 times the rate of murder in the U.S. today.

That led to a backlash of vigilantism through Councils of Vigilance and a rash of lynchings of robbers, killers, and even those merely suspected of crimes.

It was against this backdrop that Barton and a posse of Deputy Charles Daly, Constables William Little and Charles Baker, and an interpreter left L.A. in pursuit of Flores, Pancho Daniel and their gang of robbers, also known as Las Manillas, or the Handcuffs.

Little is known of Flores before his rampage. What is sure is that he was a convicted horse thief who had escaped from San Quentin. After a foiled attempt to rob a wagon laden with supplies, he and his gang ransacked homes and businesses in San Juan Capistrano and murdered a merchant.

Orange County Undersheriff Jeff Hallock, left, and Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna in front of the Barton Mound memorial plaque in Irvine commemorating the four law enforcement officers who were killed during a 1857 gun battle with outlaws in what was then Los Angeles County.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Although Barton, a big and brash Missourian, had been warned that a large gang of robbers was on the loose and lying in wait, he and his under-sized group went in search of the murderous band. Barton was in his second term as the Sheriff. Stanley described Barton’s pursuit of the gang as foolhardy but in keeping with his character.

“This was like Custer,” Stanley said. “Barton was arrogant. He was so aggressive.”

While on patrol, Barton and his posse were lured to the hillside and ambushed by a member of the gang, and the gun battle ensued. The interpreter fled the scene.

According to Stanley, during the battle Barton was initially wounded by Daniel and, after emptying his revolver and finally flinging his gun at his attackers, was shot in the face by gang member Andres Fuentes.

The aftermath

A number of large posses of lawmen, militia, citizens, and vigilante gangs were assembled to hunt down the Flores Daniel Gang.

One, led by General Andres Pico, apparently cornered Flores in the nearby canyons. However, the desperado added another chapter to his legend, allegedly making a daring escape down a perilous hillside that now bears his name. Flores’ freedom didn’t last long as he was later captured and hanged in Los Angeles in February 1857.

In the vigilantism that followed, more than 52 alleged gang members were rounded up and 18 hanged for murder. Daniel eluded capture until January 1858. While awaiting trial in Los Angeles in November 1858, a vigilante group lynched Daniel at the jail. No one was accused or prosecuted. Fuentes, who fired the fatal shot, escaped to Mexico.

A plaque commemorating the four law enforcement officers, including Sheriff James Barton, who lost their lives during a 1857 gun battle with outlaws at what is now called Barton Mound.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

After the ambush, Barton and the posse were recovered and brought back in coffins to Los Angeles by wagon.

Historian Harris Newkirk in “Sixty years in Southern California, 1853–1913” wrote, “when the remains were received in Los Angeles on Sunday about noon, the city at once went into mourning. All business was suspended, and the impressive burial ceremonies, conducted on Monday, were attended by the citizens en masse.”

One last piece of business pertaining to the lawmen’s legacy remains to be completed, according to Stanley.

Barton and his posse were initially buried in Los Angeles is an area later purchased and paved over by the Los Angeles Board of Education. They were moved and later lost as unmarked graves. However, Stanley said those sites have now been found and will be honored.

Perhaps, as with the Barton’s Mound plaque, it will, as Luna said, “honor a brave man, him and his entire posse.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge