It all started when her husband stepped in front of a train in Dana Point in 2012.

The pain led her to a grief support group. It helped so much that she went to school to became a grief recovery specialist for others.

At her very first group session, four moms showed up. Every one of their children had fatally overdosed. The trend continued.

“It was so painful and heartbreaking that I felt the need to go to the other side, and talk to the addicts to help prevent what was happening,” Kristi Hugstad says.

Orange County Coroner statistics from 2014 show 315 people dying that year from accidental overdoses. Another 77 overdosed on purpose, committing suicide by drugs.

“Alarmingly,” the coroner’s report says, “there has been an 84 percent increase in heroin deaths since 2012.”

So earlier this year, Hugstad started another sort of grief group. This one for addicts. And what are they grieving? The death of their addiction.

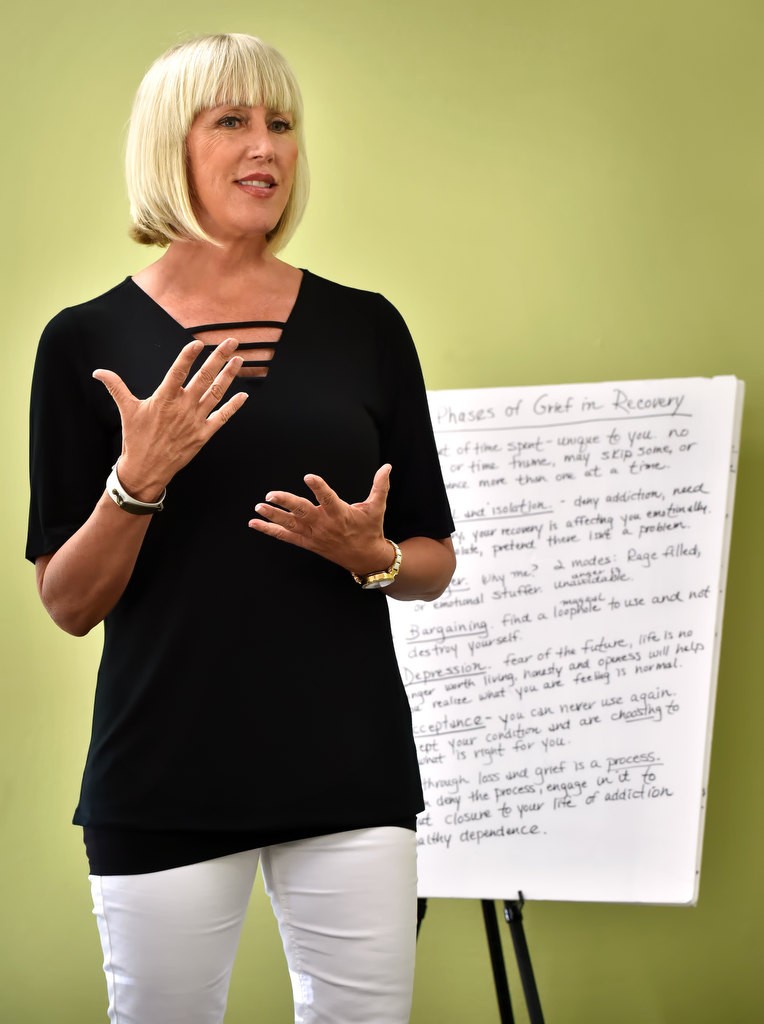

A group session at Reflections Recovery in Fountain Valley for recovering addicts.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“They mourn the relationship, the escape, the distraction and the excitement they had with their substance,” she says. “They’ve given up not only their drug, but their entire lifestyle. I let them know it’s OK to miss all that — that it’s normal and healthy to grieve their addiction.”

Hugstad’s efforts dovetail with several programs the Orange County Sheriff’s Department has in place to help keep people clean.

“Increases in drug overdoses in Orange County concerns me greatly,” said Sheriff Sandra Hutchens. “Our Drug Liaison Officers and Drug Education Sergeant, along with our nonprofit partners including Drug Use Is Life Abuse, are working diligently to educate the community and find solutions that will decrease the number of overdoses.”

Hugstad views addiction the same as a death of a close friend or family member.

“The relationship to their addiction is that intense and intimate,” she says. “They need to grieve it like a death. And say goodbye to it forever.”

And if you’re at the rock-bottom point where you’re saying goodbye to an addiction, odds are you’ve probably already said goodbye to some other pretty important things: Like maybe your job, your family, your house, your health — so you’re grieving those losses, too.

Kristi Hugstad talks about the phases of grief as she leads a group session at Reflections Recovery in Fountain Valley.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

Hugstad holds meetings twice every Tuesday and Thursday at Reflections Recovery Center in Fountain Valley.

On a recent Tuesday morning, nine addicts showed up, all but three of whom quit heroin. The others were meth addicts. And all said they enjoyed Xanax.

Only two of them were young women. The rest were young men.

Hugstad talked to them about the Kubler-Ross model of five stages of grief with the caveat that they might not go through every one.: Denial (I’m not an addict). Anger (at themselves, the drug, God). Bargaining (Just one more time and then I’ll quit). Depression (How am I going to survive without my drugs or drinks?). Acceptance.

By understanding that these are all normal responses to grieving a loss, Hugstad hopes, the addicts will hang in there until acceptance.

She asks group members to write a goodbye letter to their addiction.

One young man got applause after he “told” heroin it was over.

“I don’t think I would have survived it had I not had drugs,” he said of his early life. “But there’s no more use for that. Whatever use it did have it no longer does. It was there for me when I was in pain, depressed, anxious, when my friends walked away from me, because of heroin. There was a beautiful place inside myself I found, but the path evaporated.”

Hugstad is heavy on finding an alternate passion to fill the void, to wake up every day with a purpose and find something pleasurable to raise the dopamine levels naturally.

“Being an addict is almost a full-time job. You’re used to spending all day getting high and making connections to get high, so now you need to fill that time…find a positive way to spend your day,” she says. “It could be something as simple as music. Just being around family.”

Alex shares his views during a group session at Reflections Recovery in Fountain Valley.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

One way or another, you need to “find your way through the tunnel of grief.”

She had to do this herself.

Hugstad’s husband, Bill Brotherton Jr., a popular bodybuilder and fitness club owner in Dana Point, was 54 when he took his life. At first Hugstad blamed years of steroid use. Now she believes it was a cocktail of prescription drugs he was taking: valium to sleep, seroquel for manic depression, xanax and klonopin for anxiety.

“I cried and I beat on pillows and I screamed at Bill: ‘How could you do this?’ But most importantly, my way of healing is to get out there and help someone else. If I could save one of these addicts from going back out, and instead live a clean and sober and healthy life, that’s the best thing I can do for my personal healing.”

In most cases, the addicts Hugstad meets with are grieving more than the death of their addiction. They’re also grieving the death of friends.

Hugstad asked for a show of hands whether anyone had a friend who died by drugs. Every hand went up. One 25-year-old Huntington Beach man said he had 10. Some of them were there when the friend overdosed. Another young man in the group lost his younger brother to an overdose.

“When you’re an addict, it’s part of the game,” Hugstad says. “Their greatest fear is not death. It’s living sober.”

But when a friend dies, guilt kicks in, with the nagging question of could I have saved them?

“I feel that, too,” Hugstad says, regarding her husband. “My purpose here is to offer hope. To tell them that they’re not alone. Someone else is sharing their pain.”

And there are unfortunately more than enough young people out there to share the pain.

Hugstad recalls one talk she gave to health classes at San Clemente High last year. Afterward, a line of students spilled out the door. Kids telling her they were cutting, pulling out their hair, their eyelashes, being cyberbullied, being pressured to try drugs every day on the walk home.

In addition to the grief groups, Hugstad (who is also a credentialed health and physical education teacher) has a podcast on OC Talk Radio called “The Grief Girl.” And she blogs about grief for the Huffington Post.

“Friends and family only see the pain and destruction the drugs caused,” she says. “They don’t understand the passionate relationship the addict has with their substance.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge