Editor’s note: Michael W. Streed is a retired Orange Police sergeant, owner of SketchCop Solutions and author of the book, “SketchCop: Drawing a Line Against Crime.” You can get his book here. Behind the Badge periodically will share excerpts from his book.

…On Sunday, April 16, 1995, two days after (former Fullerton PD Officer Robert T.) Walsh’s disappearance, the Orange Police Department made a grisly discovery after responding to an emergency call of an explosion and vehicle fire in the alley to the rear of a business behind a local strip mall.

The Fire Department responded quickly to extinguish the flames. Police soon learned the vehicle was owned by Wells Fargo Armored Services and was the same vehicle driven by Walsh when he was reported missing.

Inside the vehicle, police found a burned body, later identified by fingerprint comparison as Walsh. Evidence at the scene suggested the killer used an accelerant to ignite the car. The fire had been fast burning. The Fire Department’s quick response thwarted the effort to destroy evidence and made it possible to preserve much of the scene.

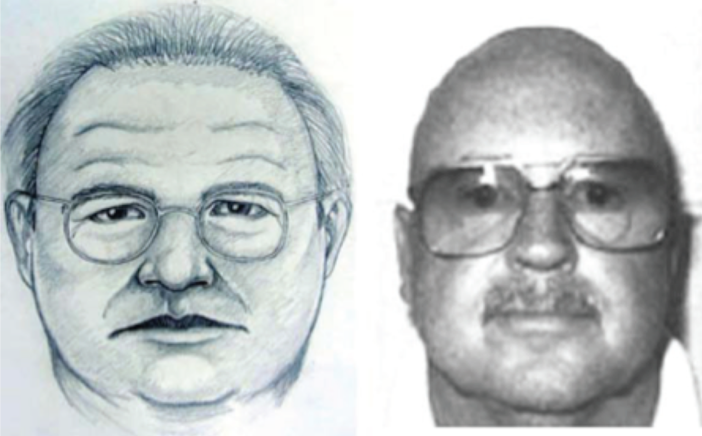

Witnesses said they saw a man running from the vehicle about the same time it caught fire. They described him as a “pudgy” white male, approximately 50 years old, 5-foot-10 to 5-foot-11 in height, approximately 180 pounds with gray hair, wearing glasses. The man, who police considered a suspect, had hurriedly run off in a westerly direction. His path was traced later by a Sheriff’s Department bloodhound that lost the scent a few blocks away.

Now that police knew Walsh’s fate, they were left to ponder why. Was he taken by surprise at his last known stop? Or, was there an armed confrontation he was unable to talk his way out of?

An autopsy and evidence examination was conducted in an effort to answer these questions.

Pathologists determined Walsh suffered blunt force trauma to his head prior to his death. Markings on both sides of his head suggested he was struck with a tool similar to a tire iron. His lack of defense wounds convinced police he had been surprised by his attacker.

Walsh also suffered a fatal gunshot wound to his head. The bullet, possibly from a .38 caliber handgun, entered on the left side and angled toward the back of his head, where the bullet came to rest, causing a fracture to his skull.

Further autopsy results showed that he also suffered significant burns to the lower portion of his body and that some hair fibers were found on his shirt.

Detectives would need to turn back to their eyewitnesses if they hoped to find Walsh’s killer. Up until now, they were unable to find conclusive forensic evidence that would help them identify a suspect. They began conducting follow-up interviews with two eyewitnesses who saw the subject in and around the area of the murder.

Detectives approached me and asked if I could work with them to develop a suspect sketch. A witness had seen the subject inside a nearby fast food restaurant after the murder. Moments later, he saw the man on a pay phone outside, on the same corner where the sheriff’s bloodhound lost his scent.

The other witness, a woman, had seen the subject throwing something into the vehicle before it burst into flames.

There was nothing remarkable about these two witnesses. I would describe them as passive witnesses. Sometimes such witnesses can be difficult to work with because there is less “imprinting” of an event within their memory. Studies have shown higher trauma results in the event becoming more deeply embedded within one’s memory. However, if handled correctly, these witnesses can provide police with a phenomenal amount of information.

Now, the only obstacle to overcome was their distance from the suspect and the short time they observed him as he fled the area.

In addition to those difficulties, there was a strong likelihood for conflicting descriptions if the witnesses weren’t interviewed properly. Multiple witness interviews demand much concentration and guidance from the interviewer.

Often, stronger personalities emerge and attempt to hijack the interview. Eyewitness confidence does not always translate to better identifications. Sometimes the submissive personality has better cognitive skills and can be the better witness. It’s up to the police sketch artist to recognize this and exploit an eyewitness’ strengths and weaknesses in order to guide the interview to a successful conclusion. There have been many times I’ve left a multiple-witness interview totally exhausted.

Luckily, these two were a rare commodity. They were good citizens eager to assist police and share what they saw. They worked well together and actively took part in the interview. In the end, they helped develop a composite sketch that appeared to mirror their first impression: the face of a pudgy, older white man (suspect Bill Charles Poynor)…

Editor’s note: Walsh worked at the FPD from 1961 to 1966 and medically retired with a knee injury.

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge