Ever since former Westminster policemen Sgt. Tom Richard and Officer Ken Pate died from self-inflicted injuries 10 and 11 years ago, respectively, the local police agency has been at the forefront of advocating for suicide prevention and mental health awareness.

At the start of Mental Health Awareness Month, the Westminster Police Department and guests gathered in a main hallway to recognize the two fallen officers with the unveiling of a mounted oversized green shoulder patch with framed portraits of the two officers.

Beneath the patch was a message that read, “To anyone out there who’s hurting, it’s not a sign of weakness to ask for help, it’s a sign of strength.”

A Westminster PD officer wears the new green Mental Health Awareness Patch, to be worn for the month of May, raising awareness for Mental Health.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

The surrounding wall is painted a bright Kelly green, the color that represents the month and is meant to symbolize new growth, new life, and new beginnings.

For the first time, the two officers are being commemorated in a central space in the police department.

Throughout the month of May, officers in the department can wear green shoulder patches, while professional staff will be offered green ribbons and lapel pins, to support the cause.

In addition to Richard and Pate, Westminster lost three officers early: Lt. Ronald Weber, Ofc. Steven Phillips, and Sgt. Marcus Frank. Weber and Frank died from work-related illnesses, while Phillips, a motorcycle officer, perished in a traffic accident while on duty. Those three are recognized with plaques on the Westminster Police Officers’ Memorial in City Plaza.

The battle to remove the stigma of suicide and recognize mental health as just that — a health issue — is slow and ongoing.

“It continues to shift in the right direction,” said Dr. Heather Williams, who specializes in treating mental health issues among first responders in her private practice and has more than 20 years of experience responding to critical incidents.

“There’s a lot of despair, a lot of fear,” said Williams, who has seen and treated many police and first responders with suicidal thoughts.

“We are exposed to humanity at its worst on a daily basis,” Westminster Chief Darin Lenyi said at the unveiling, noting the sky-high numbers of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression in police.

Asking for help

Carrie Atkinson, Richard’s widow and a former WPD officer, came to the unveiling and spoke about the importance of seeking help for those in distress.

“You don’t want to lose someone and then see someone like me standing here,” she said. “(Richard’s suicide) turned my life upside down and having to raise four kids.”

In addition to being dedicated to the fallen officers, Lenyi said, “This wall is also a reminder that it’s OK to not be OK and seek help.”

While true in concept, it is easier said than done.

“I saw things that warranted seeing someone and didn’t,” Atkinson admitted. “Instead you go home and think you’re normal, and you’re not.”

Life and the job don’t stop, especially with family and other concerns, the stress and depression can build. Sometimes officers are able to deal with it, but some can’t. Though suicide is at the farthest end of the mental distress spectrum, police also experience high rates of divorce, substance abuse, and other adverse outcomes.

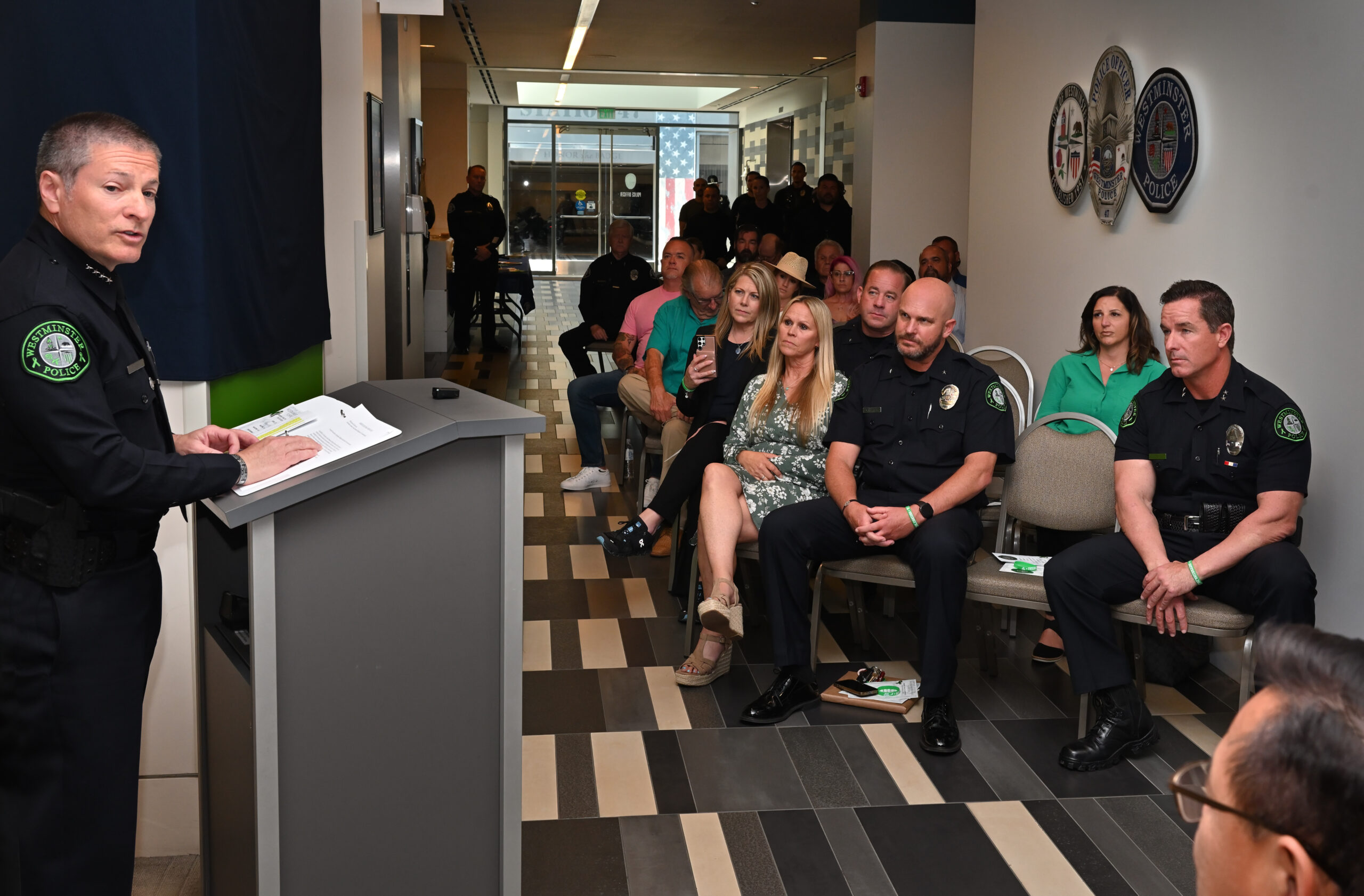

Westminster Police Chief Darin Lenyi talks about mental health telling his officers that it is “okay not to be okay,” trying to remove the stigma of seeking help with depression during a Mental Health Awareness Patch Dedication and Unveiling Ceremony at the police department.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

Steve Hough is a former policeman and cofounder of Blue H.E.L.P., which advocates for first responders and tracks the numbers of those who died by suicide. He says those going into law enforcement or other high-stress areas of public service need to consider, “what it entails being a first responder and putting on that uniform.”

Beyond witnessing and experiencing potential trauma, there are family disruptions such as demanding work schedules, odd hours, missed holidays, and other everyday concerns.

“There’s a lot to be done to raise awareness of families,” Hough said.

Although departments are doing a better job of providing mental health support, more needs to be done. With the enlightenment of the need for better attention to mental health, the Department of Justice issued a report to Congress in support of a Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act.

According to the report, “Good mental and psychological health is just as essential as good physical health for law enforcement officers to be effective in keeping our country and our communities safe from crime and violence.”

In 2023, about $9.5 million in funding was available to implement projects. While the number may sound impressive at first blush, with 18,000 law enforcement agencies and about 800,000 officers, the funding doesn’t go far.

Elephant in the room

Despite the rise in awareness about mental health, for many, talking about suicide remains off limits.

“It’s a very sensitive subject. It’s a dirty little secret this profession has,” said Cmdr. Cord Vandergrift, who was one of Richard’s closest friends.

In fact, Vandergrift and Richard spoke about suicide and about Pate, who hanged himself, just a day before Richard died.

“(Suicide) is still outpacing all other line-of-duty deaths,” Hough said.

In 2022, Hough’s organization recorded 160 police deaths by suicide, tracking reports from family, commanders, agencies, and social media — down from 196 in 2019. As of May 4, police suicides for 2023 were listed as 35.

“We fully expect the numbers are under-reported,” Hough said, due to the remaining stigma.

Hough’s group, which also offers services to officers and their families, began collecting suicide data on police in 2016, expanding to all first responders in 2019.

Police who died from suicide are not recognized on the California Police Officers Memorial. Even in an enlightened department such as Westminster, Pate and Richard have not been added to the city monument after more than a decade of discussions.

Carrie Atkinson, who’s husband, WPD Sgt. Tom Richard, committed suicide in 2013, shares a light moment with friends, Westminster PD Deputy Chief Darin Upstill, left, and Commander Cord Vandergrift before the start of a dedication ceremony at the police department to raise Mental Health Awareness.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge

For many, accepting suicides as line-of-duty deaths is a bridge too far. The stigma of suicide is deeply ingrained in religion and society as something that is not discussed.

“Some people are naive and believe it’s a choice. It’s not,” Vandergrift said.

In 2022, a Washington Post staff editorial came out in favor of suicide as a line-of-duty death in an editorial. Otherwise, the topic gains little traction. Spouses and families of officers who die by suicide often find attaining benefits can be difficult and certainly not well publicized.

President Biden signed the Public Safety Officer Support Act of 2022 into law. The act expands the original 1976 local to extend disability and death benefits to families of officers who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder or die by suicide in the line of duty. However, the Act only covers suicides after Jan. 1, 2019.

“I feel like (suicide victims and families) should be recognized, because what police officers go through and have to deal with on a daily basis is not normal,” Atkinson said.

Hough, who has been in the middle of the discussions about accepting suicide as a tragic consequence of the job along with other line-of-service deaths, said progress is slow.

“It remains very controversial. It cuts clean across from chiefs or sheriffs on down. That will always be there and there will never be a totality of agreement,” he said. “That’s a long, long battle, but we’re trying to make it happen. It varies agency to agency, county to county, state to state.”

Hough said he even runs into resistance from families of suicide victims who are ashamed and don’t want the cause of their loved one’s death revealed.

“We realize (victims of suicide) need to be recognized,” he said. “It’s become such a complex issue.”

The story of Richard

Nowhere is that complexity more evident than in the story of Richard.

Part of the overwhelming irony is that he was at the forefront of advocating for mental health for police officers and first responders dealing with trauma. In the department, he was often called Dr. Richard, after earning a doctorate in psychology.

In 1996, Richard helped start the Westminster Police Department’s Trauma Support Team, which became a model for other law enforcement agencies. Led by a licensed psychiatrist, the Trauma Support Team was established to assist officers who had experienced severe trauma – just as Richard had.

“It was a new idea in law enforcement at the time,” retired Westminster policeman Dan Schoonmaker told Behind the Badge in 2019. “We were on the leading edge of it. I think Tom did it out of his desire not only to help other people, but to find answers for himself.”

Richard was gearing up to open a private practice with two other retired officers, specializing in treating officers with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental illnesses.

And yet, Richard was stalked by his own demons that eventually overtook him. For all that he gave to take care of others, he failed to adequately take care of himself. Before his death, Richard left clues that would only become obvious later, although they may not have made the tragedy any less avoidable.

“I remember him at Ken’s funeral and seeing (Pate’s) family devastated,” recalls Atkinson. “It was too much. I know he felt a lot of guilt.”

In many cases, Richard was called on for peer-to-peer counseling at other agencies. However, with Pate in the same department, it would have been a conflict of interest for Richard to counsel his friend.

“I know he felt a great loss,” Atkinson said. “He felt he could have helped.”

After Pate’s death, Richard began drinking heavily and taking medication for anxiety and depression. He joined Alcoholics Anonymous and even received a 90-day chip for sobriety.

Then there were the horrors he witnessed. There was the man who slit the throat of the family dog in front of his 9-year-old at the beach, then returned home where he made the boy watch as he shot and killed himself.

Or the man Richard had to shoot to avoid being run over. Or the image of a lifeless seven-year-old girl who had been run over by a truck.

The most personal and hardest memory to reconcile had dogged Richard since Christmas 1988. As a rookie patrol officer, Richard received a Code 3 emergency call and took off, sirens screeching and lights flashing. As he passed 80 miles an hour, he struck a car that had entered an intersection, killing the two young women occupants.

Although a jury in Westminster acquitted Richard of vehicular manslaughter, the ruling could not erase the guilt Richard carried to his death.

When he was discovered the day after his suicide, Richard was slumped next to a crypt at Pacific View Memorial Park, the same cemetery that held the remains of Jessica Warren, one of the women who died in the accident.

There was a final irony for those Richard left behind.

As Atkinson watched the bleak tableau of Pate’s family at his funeral she said, “I never knew this would be part of my own future.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge