Two men play chess at a table in the day room.

At another table, a man airs out a towel.

Near them, a few dozen men slumped into chairs watch a TV mounted high above them, while behind them, on the second floor, several men stroll into and out of open showers.

Above the roughly 400 inmates, obscured in a guard station in the center of the multiple-bunk dormitory in the maximum-security Theo Lacy Facility in Orange, two deputies and a couple of higher-ups wearing suits and ties are talking.

“There are drugs out there right now,” one of them says. “And weapons.”

Sgt. Mike Few, left, and Lt. Andy Stephens of the OCSD Custody Intelligence Unit, inside the control room of Mod J, a multiple-bunk dormitory inside the maximum-security Theo Lacy Facility in Orange.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

The men in suits are Lt. Andy Stephens and Sgt. Mike Few, who a year ago were tasked to build, from the ground up, the OCSD’s new Custody Intelligence Unit.

The CIU, primarily an investigative unit, was among several reforms instituted by Sheriff Sandra Hutchens in the wake of accusations that the OCSD and county prosecutors were running an illegal network of informants in county jails.

Although a Grand Jury report declared no such formal program exists, it also found that lax supervision led to misuse of jailhouse informants by a few deputies.

The CIU was created Sept. 30, 2016 after the OCSD dissolved its Special Handling Unit, a team of deputies who were in charge of managing informants throughout the Orange County Jail system.

The CIU since has grown into a team of five investigators and two investigative assistants managed by Stephens and Few. Managing the informant program actually accounts for only a small portion of what the team does. The unit’s main task is targeting criminal activity in the county’s jails.

An OCSD deputy keeps watch on inmates in a module at the Theo Lacy Facility in Orange.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“Because of recent (litigation and court findings), most of the public is under the impression that everyone in jail is an informant, and that we’re developing informants and we’re managing them and using them,” Stephens said.

In reality, the number of informants who work with CIU investigators is very low, Stephens said.

“It’s not something we seek or pursue — it’s something available to us if we choose to use it,” he adds, noting that information from informants is notoriously unreliable.

“The old Special Handling Unit guys did a lot of good work,” Few said, “but it’s no secret some mistakes were made, so the department decided to take a more professional approach.”

The CIU’s core mission is to provide for the safety and security of the O.C. jail system, whose five facilities on any day house some 7,000 inmates.

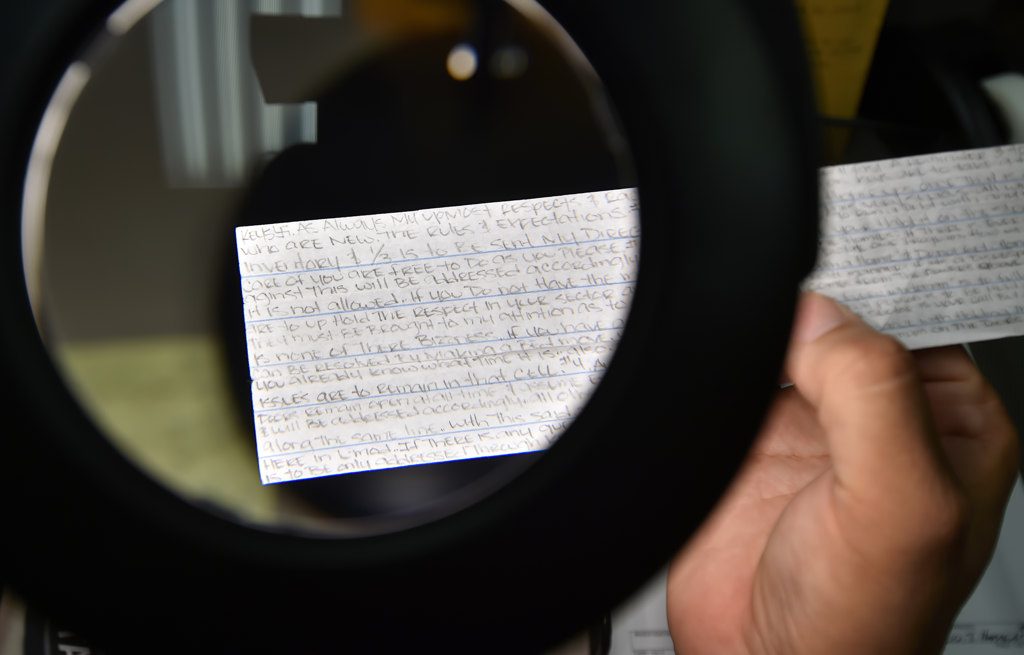

Instructions on a “kite” intended for inmates. The note is written so small you need a magnifying glass to read it.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

On a recent weekday, there were 3,240 inmates at the Theo Lacy Facility (the largest in the system) and a total of 6,405 countywide.

The CIU primarily maintains the safety and security of O.C. jails by investigating crimes, mostly related to drugs and assaults. More serious offenses, like murder, attempted murder and sexual crimes, are investigated by other specialized units within the OCSD.

When Stephens and Few started the CIU last year — on the same day both were promoted to their current ranks —- they had little more than a table, phones and computers in a small space in the administrative offices of the Theo Lacy Facility, which is run by Capt. Jason Park and staffed by about 450 sworn and professional staff members.

Now, the CIU is a full-fledged team with its own offices.

Since July 1, 2017, when jail-crime investigations formally were folded into the CIU after previously being handled by investigators in the OCSD’s North Investigations, the CIU has handled more than 300 crime reports involving drugs and assaults.

That works out to five crimes a day being committed in O.C.’s jail system.

OCSD Lt. Andy Stephens talks about the new Custody Intelligence Unit.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“It (amount of crime in O.C. jails) is a lot more than I ever thought it would be,” says Few, a 21-year OCSD veteran who some 15 years ago worked with Stephens as a patrol deputy in Lake Forest.

And with recently enacted legislation such as AB109, the prison realignment act that transfers responsibility for supervising certain kinds of felony offenders and state prison parolees from state prisons and state parole agents to county jails and probation officers, county jails have become more dangerous, Stephens says.

“One of our biggest challenges is investigating assault crimes,” he says. “The criminal element in our jails has become more sophisticated. Several of our inmates used to be in state prison. The gang structure is much more solidified now.”

Says Few: “Just because someone comes to jail doesn’t mean they stop committing crimes. A lot of criminals see going to jail as (acquiring) power and money.”

Jail code dictates that no inmate can squeal on another, or they will face dire consequences. A constant challenge CIU investigators face is getting people to talk.

OCSD Sgt. Mike Few of the Custody Intelligence Unit displays, while wearing gloves, legal documents mailed to an inmate at the Theo Lacy Facility in Orange that contained a blank page sandwiched between the other papers soaked in meth. An inmate could then smoke or eat the paper.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

“Even the victims of assaults don’t want to talk,” Few says.

To address this, the CIU is working more closely with the O.C. District Attorney’s Office to encourage prosecutors to file jail assault cases with or without the cooperation of victims. In most areas of the jail, a sophisticated video system is able to capture crimes as they happen.

Many jailhouse assaults are ordered from gang leaders in prisons hundreds of miles away who are able to get the word out to fellow gang members on the street or to cronies locked up in O.C. jails, Few and Stephens say.

In many cases, the deputies say, assaults are ordered because gang leaders fail to get their cut of profits from drugs sold behind bars.

“Drugs go hand in hand with violence inside jails,” Few says.

Keeping drugs from getting inside the jails is a constant battle, CIU leaders say.

“In a locked-down environment such as state prison,” Few explains, “inmates have nothing but time. They are very industrious. One of the fun parts of our job is intercepting coded communications.”

Barbed wire lines the walkways of the Theo Lacy Facility in Orange.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

He displays a “kite,” a note passed between inmates, that the CIU recently intercepted. The hand-written lettering on kites typically is so small investigators need to use a magnifying glass to read it.

This particular kite was penned by a leader of a certain housing unit. In the kite, he sets down rules to fellow white inmates.

One rule: If you’re ordered to assault someone, you must carry out the assault or you’re next.

Another: Give one-third of drugs or drug money you receive to the gang leader.

Bad guys go to great lengths to gets drugs into jails.

Some are ordered by cohorts in custody to get arrested and smuggle them in a body cavity, Few and Stephens say.

Mail is a popular vehicle, too.

Although jail deputies scan and hand-search all the mail that comes in, they are not allowed to do so with legal mail, which must be opened in the presence of the recipient inmate.

Few leaves a room for a moment and returns with a manila envelope purportedly sent to a Theo Lacy Facility inmate by an attorney.

He puts on black latex gloves and pulls out several pages of legal documents.

OCSD Lt. Andy Stephens talks about the new Custody Intelligence Unit at the Theo Lacy Facility in Orange.

Photo by Steven Georges/Behind the Badge OC

In the middle of the legal documents is a blank white sheet of paper whose stock is thicker than the other documents.

Meth can be dissolved in water.

The white sheet of paper is covered in about two grams of now-dry meth — about 20 highs. All the recipient needs to do is eat the paper or burn it and inhale.

The recipient never got the mail because he had been transferred to state prison.

It was returned to the attorney, who alerted authorities when he realized he never sent the mail and that someone had looked him up on the Internet to use his return address.

“We see this kind of stuff every day,” Few says.

Heroin also has been found under stamps. And the prescription opiate Suboxone, which comes in long, thin and colorless strips, often is found inside cards.

“An inmate will ask of such recipients, ‘Hey, you get the happy card?’” Stephens says.

As for confidential informants, any prospective one has to be vetted through the CIU as well as the DA’s office.

“It’s our least preferred method (of conducting investigations),” Stephens says.

Both CIU leaders praised jail deputies for quickly adapting to the new culture of jailhouse investigations.

“Their jobs are really dangerous,” Stephens says. “Those (deputies) are the real heroes.”

Behind the Badge

Behind the Badge